The National Book Award Backlash Begins!

It’s always amusing to watch the would-be literary gatekeepers turn brittle whenever the rest of us refuse to rubber-stamp their pronouncements on what is and is not worthy of attention—we saw it a few months ago with the backlash against franzenfreude (the snotty remarks about Jennifer Weiner’s inability to construct compound German nouns were particularly amusing), and I expect we’ll see some more of it as the reaction to this year’s National Book Awards finalists, particularly those on the fiction shortlist, bubbles to the surface.

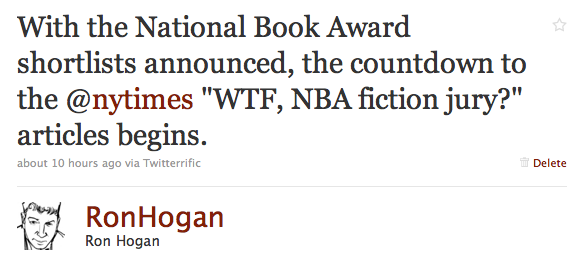

The sense of outrage at the NY Times over the National Book Awards fiction shortlist of 2004 was particularly vehement, with multiple articles devoted to explaining to Times readers why the five novelists on the award’s selection committee were out of step with what was truly significant in American letters that year. (Rick Moody, who chaired that jury, wound up writing about the situation for The Believer.) And I expected, when this year’s nominees were announced earlier today, that we’d see similar protests soon enough. I should have taken the growth of social media over the last six years into account: Laura Miller, who wrote one of the putdowns of 2004’s nominees, tweeted within an hour of the National Book Foundation’s announcements that the fiction shortlist was “pretty whacked,” adding: “I rest my case on all-novelist juries.” What, you might ask, did she mean by that?

13 October 2010 | theory |

Freakonomics & the Secret to Good Book Trailers

How do you adapt a nonfiction work like Freakonomics, which is essentially a book-length description of economic principles built around a series of illustrative set-pieces? Certainly, you’d want to interview Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt, but the producers of the Freakonomics movie, which has been available on iTunes for a while now and is gradually making its way into theaters, also brought several directors into the mix to create four short films, each tackling a different section of the book. As I watched a preview screening a few weeks ago, I was reminded of a marketing principle I used to write about frequently at GalleyCat. “When is a book trailer not a book trailer?” I once asked. The answer: When it’s a human interest story.

(Note: I’m not using the film’s trailer as an example of this, but I wanted to have something for people who haven’t seen the film yet to look at, and you’ll catch glimpses of the things I discuss in the following paragraphs.)

The parts of the Freakonomics film that are most effective are the ones that ground Levitt and Dubner’s economic principles in compelling narratives: Alex Gibney (the director of Taxi to the Dark Side) probes the history of cheating in Japan’s top sumo wrestling leagues, while Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (Jesus Camp) follows two Chicago-area ninth-graders at a school participating in a study which financially rewarded students for getting good grades—a study that was not in the original book. Each filmmaking team finds people intimately connected to the situation (or who at least can speak very powerfully about it), turns the camera on, and lets them tell their stories. The Ewing-Grady segment is particularly effective because the directors impose themselves on the unfolding narrative even more lightly than Gibney does; he’s rolling out a solid investigative journalism piece, but they’re more fly on the wall.

4 October 2010 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.