I Want to Read Like Common People

Now, it’s true, I have some issues with Oprah’s Book Club, specifically with the pattern of books Oprah Winfrey’s been picking for it over the last six years, and I even share the opinion of the bookish New Republic writer, Hillary Kelly, that Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities is an awkward pair of Dickens novels to read in tandem. (So what would I choose? Nicholas Nickleby and David Copperfield, maybe?) But that’s one of the few things I agree with in Kelly’s profoundly elitist attack on Oprah, the ruination of great literature.

Now, it’s true, I have some issues with Oprah’s Book Club, specifically with the pattern of books Oprah Winfrey’s been picking for it over the last six years, and I even share the opinion of the bookish New Republic writer, Hillary Kelly, that Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities is an awkward pair of Dickens novels to read in tandem. (So what would I choose? Nicholas Nickleby and David Copperfield, maybe?) But that’s one of the few things I agree with in Kelly’s profoundly elitist attack on Oprah, the ruination of great literature.

Kelly’s article comes across as one lone note of resentment that Oprah Winfrey, rather than the official gatekeepers of the literary canon, is convincing people to read Dickens and Tolstoy—of course, if Oprah’s making the recommendation rather than, oh, I don’t know, Harold Bloom, it stands to reason that she must be encouraging us to read these books for the wrong reasons. Seriously: Kelly says the Book Club’s selections stem from “a generally wrongheaded view of novels,” one through which “the Book Club has carved its niche among readers by telling them that the novel is a chance to learn more about themselves. It’s not about literature or writing; it’s about looking into a mirror and deciding what type of person you are, and how you can be better.” So, you see, I’m not just invoking Bloom off the top of my head:

“If we read the Western Canon in order to form our social, political, or personal moral values, I firmly believe we will become monsters of selfishness and exploitation. To read in the service of any ideology is not, in my judgment, to read at all. The reception of aesthetic power enables us to learn how to talk to ourselves and how to endure ourselves. The true use of Shakespeare or of Cervantes, of Homer or of Dante, of Chaucer or of Rabelais, is to augment one’s own growing inner self. Reading deeply in the Canon will not make one a better or a worse person, a more useful or more harmful citizen. The mind’s dialogue with itself is not primarily a social reality. All that the Western Canon can bring one is the proper use of one’s own solitude, that solitude whose final form is one’s confrontation with one’s own mortality.”

(And Bloom wrote The Western Canon well before Winfrey had made her first Book Club selection!)

15 December 2010 | theory |

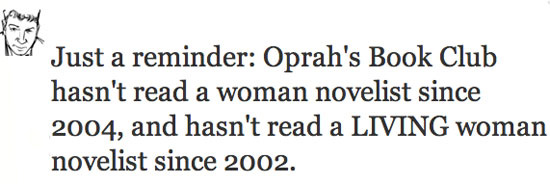

Oprah Winfrey’s Book Club for Men

When the news broke that Oprah Winfrey’s book club was following up Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom with a double shot of Dickens (Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities), it got me to reflecting once again: Does it matter that Oprah’s Book Club hasn’t read a novel by a woman writer since Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, and that they haven’t read a contemporary novel by a woman since Ann-Marie McDonald’s Fall on Your Knees? I got a lot of feedback when I raised this issue on Twitter; a few people took the “it’s her club and she can pick what she wants” tack, and others rightly pointed out that it’s not as if Winfrey hadn’t had any women writers on the show, but most were disappointed at the imbalance. As Washington Post book critic Ron Charles pointed out, it’s hard to imagine putting together a lineup of the most significant contemporary fiction writers that isn’t predominantly female.

So I had another look yesterday afternoon at a book I’d read earlier this year, Bring on the Books for Everybody: How Literary Culture Became Popular Culture, to focus my thoughts on the Book Club issue. (Full disclosure: Jim Collins was my college mentor.) I’m particularly interested in the way, as Collins puts it, “Oprah functions as an authority on reading for an imagined community of self-cultivators that numbers in the hundreds of thousands and who come to her expertise within the heart of consumer culture.” With so many books to choose from, how does a reader who aspires to be “literary,” or at least “well-read,” decide where to start? That’s where Winfrey comes in—and the particular genius of the Book Club’s 21st-century incarnation is that it combines the original (pre-Corrections) emphasis on the emotionally sublime power of “great books” with an emphasis on the symbolic credibility of “Great Books.”

And that leads directly to why I feel the absence of women writers in the Book Club matters.

7 December 2010 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.