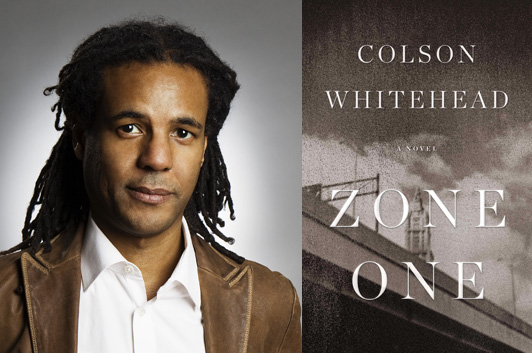

Read This: Zone One & the Literary/Genre Blur

Last month, one of my Character Approved book selections was Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, a novel about a foot soldier in the battle to reclaim lower Manhattan after the zombie apocalypse. It’s a great story, especially if you’re already a fan of Whitehead’s cool, detached voice, which fits this world—where everybody suffers from one form of “post apocalypse stress disorder” or another—perfectly. Like many classic zombie stories, Zone One has its share of satirical social commentary, including some unsettling echoes of Abu Ghraib, but at its core, this is a story of existential isolation… with some kick-ass action sequences.

Much of the critical reaction to Zone One centers around the “fact” that Whitehead is a “literary” author who’s decided to move into genre—which sort of ignores the weirdness of his first novel, The Intuitionist, but Whitehead himself doesn’t care about the distinctions between literary and genre fiction: “They don’t mean anything to me,” he says in an Atlantic interview. “They’re useful for bookstores, obviously. They’re useful for fans. You can figure out what’s coming out in the same style of other books you like. But as a writer they have no use for me in my day-to-day work experience.” Some critics, and critical institutions, care a lot, which is how you wind up with ridiculous, insipid statements like the lead sentence of Glen Duncan’s NYTBR review of Zone One: “A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star.”

At first glance, one wonders why the New York Times would assign a “genre” novel to somebody who is so actively resentful of genre fiction and its fans—even as he makes big money from Knopf off werewolf stories—when they’ve already got a thoughtful critic of horror fiction in Terrence Rafferty. Maybe he just didn’t want to revisit zombies after surveying the topic back in August, or maybe the book review’s editors set out to deliberately provoke the sort of controversy that generates a lot of page views. Your guess is as good as mine. (Meanwhile, Charlie Jane Anders did a fine job of demolishing Duncan’s two-pronged cultural snobbery.)

Using Zone One as a prominent example, Joe Fassler wrote an article for The Atlantic about the increased presence of genre tropes in literary fiction, and I think that article gets at some salient points about how “today’s serious writers” are “yoking the fantasist scenarios and whiz-bang readability of popular novels with the stylistic and tonal complexity we expect to find in literature.” I’d suggest, though, that the “sea change,” to use Fassler’s description, isn’t in what “serious writers” are doing but in what “serious critics” are noticing and/or willing to discuss. We’ve always had writers who’ve combined “genre tropes” and “literary grace” in their fiction; some of them were published as science fiction or fantasy, some as mainstream literary fiction. (The principle holds true for other genres as well.) And this recent wave of high-profile novels with genre elements certainly hasn’t negated the persistence of realism as a literary device… More thoughts in this vein soon.

It Became Necessary to Destroy Huckleberry Finn in Order to Save It

Our literary 2011 got off to a contentious start with the news that NewSouth is about to publish an edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with a certain racial slur expunged from its vocabulary; instead, Huck and the adults around him will consistently refer to Jim as a “slave.” (It also includes a version of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer with “Indian” instead of “Injun,” but that’s not where all the attention is going.) Auburn professor Alan Gribben explained to the New York Times that he felt awkward having to say a certain word in front of students, and he didn’t think they much liked it either; as he writes in the introduction to his bowdlerized edition, “Even at the level of college and graduate school, students are capable of resenting textual encounters with this racial appellative.” Getting rid of that word, he insists, is the only way he can put the book in front of students to make them appreciate Twain’s incisive social critique.

Well, very few people apart from Prof. Gribben and his publisher seem to think this was a good idea. Perhaps Ice-T says it best:

As Ishmael Reed observed in The Wall Street Journal, “Twain used the words with which he was surrounded and to insist that he omit words is not only to put a gag on his characters but a gag on the Age.” Tayari Jones, in an op-ed piece for AOL News, echoed Reed’s point about Twain’s deliberate reflection of a painful and historical reality, adding: “The solution is not to fight willful ignorance with willful misrepresentation.” They’re both right: It’s one thing if the brutality of race relations in the United States in the years before the Civil War makes Alan Gribben uncomfortable—it’s another thing to create a deliberately false version of that society so he and like-minded educators can feel good about themselves. Gribben and NewSouth have not only done American literature a disservice, they have failed the students in any educational institution shallow enough to buy into their debased product.

6 January 2011 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.