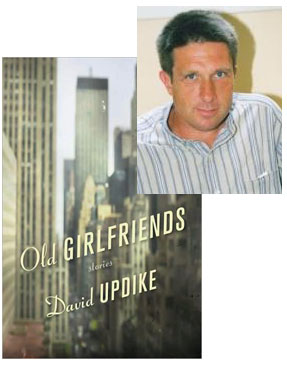

David Updike and the Fool’s Errand of “Araby”

After reading David Updike’s “Selling Shorts” guest essay this weekend, I felt like I’d been let in on a secret running through several of the stories in his latest short story collection, Old Girlfriends, an undercurrent of equal parts confusion and compulsion. There’s plenty of other things going on in these stories—”A Word with the Boy” and “Love Songs from America,” for example, tap into those moments when fathers realize they can’t protect their sons from the world, and how such moments affect their relationships with both sons and world—but even those Updike characters making a conscious effort to understand their emotional lives, like the in-analysis protagonist of the title story, find themselves stumbling through incidents they can’t quite get a grasp on, wondering how they’re going to make it through.

It may have been in high school that I first read the story, or maybe college, in the freshman writing class for in which I received a C on every paper I wrote and also for the final grade. And I must have carried a tattered copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners when I took a semester off two years later, and made my own ill-planned visit to Ireland, in the middle of January. I spent several lonely weeks in chilly bed and breakfasts, pubs where all backs seemed to turn toward me when I came in, after wandering for hours through the gray cold streets of Dublin with my camera and red backpack.

But whenever I read this short story, “Araby,” it struck a chord in me, echoed some of my own, deep childhood preoccupations: the stubborn slowness of time; the hopeless longing for inaccessible, older girls; the inability of the adult world to be of much use to me in my private, emotional quests. There was also the beauty of language, of words being used in strange and pliable ways:

“The cold air stung us and we played until our bodies glowed. Our shouts echoed in the silent street. The career of our play brought us down through the dark muddy lanes behind the houses where we ran the gauntlet of the rough tribes from the cottages, to the back doors of the dark dripping gardens where odours arose from the ash pits, to the dark, odorous stables where a coachman smoothed and combed the horse or shook music from the buckled harness.”

I could hear this music, knew well the glowing bodies in cool air at dusk on autumn afternoons, the air smelling of burning leaves. And then, the crux of the matter, girls like Mangan’s older sister, impinging herself on our simple, boyish needs: “She was waiting for us, her figure defined by light from the half opened door. Her brother always teased her before he obeyed and I stood by the railings looking at her. Her dress swung as she moved her body and the soft rope of her hair tossed from side to side.”

The soft rope of her hair! Her dress swung as she moved her body! I, too, had been haunted by the clothes and mysterious movements of older sisters—their distant carelessness, vague awareness that they were being noticed, willingness to draw me toward them.

6 September 2009 | selling shorts |

J.C. Hallman, Lost In His Own Funhouse

J.C. Hallman uses a variety of metafictional starting points to set the stories in The Hospital for Bad Poets in motion. In the title story, for example, the critical treatment of an emerging poet is treated as if it were a medical diagnosis; “The History of Riddles” takes a couple preparing to entertain another couple in their home as an opportunity for philosophical reflection upon the ritualistic nature of games and social bonding. Then there’s “Double Entendre,” which is simultaneously an erotic story and a structural analysis of erotic stories—and in this essay, Hallman talks about the classic postmodern short story that inspired him to work within that particular framework.

If I think back through The Hospital for Bad Poets and compile a list of the authors and stories that I was more or less consciously emulating while I wrote, I pretty quickly wind up with the table of contents of an anthology I’d buy given the opportunity:

- “The Hunger Artist,” Franz Kafka

- “The Old Forest,” Peter Taylor

- “Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee,” James Tate

- “The Swimmer” and “The Enormous Radio,” John Cheever

- “Star Food,” Ethan Canin

- “The Lottery,” Shirley Jackson

…and most important for this essay:

- “Lost in the Funhouse,” John Barth

Excavating one’s own literary heritage is both interesting and problematic. It’s interesting from a critical standpoint—assuming you find origins interesting—and it’s problematic for the same reason that civilizations in Italy are problematic: dig for bedrock and all you find beneath you are the folks who got there first, the ones that beat you to it. Plus, it’s not really supposed to work like that, is it? That is, at least when it comes to fiction, we expect a little imitation early in one’s career—the bush leagues, call it—but eventually you’re supposed to discover your “voice,” sail for terra incognita, volley forth like St. George to wherever there be dragons.

Except it’s never really been like that for me. And I’ve always been a bit jealous of poets in this regard.

19 July 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.