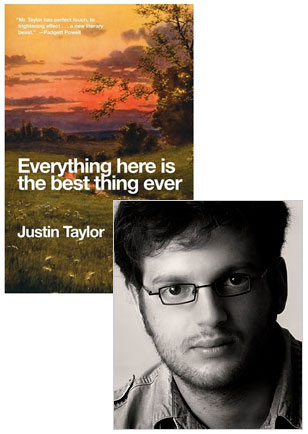

What Justin Taylor’s Learned from “The Crazy Thought”

I’m not a bad son. Only prodigal,” says the narrator of one of the stories in Justin Taylor’s debut collection, Everything here is the best thing ever, and it’s a sentiment many of his characters could share. Sure, on the surface, they look like screwups, and let’s face it some of them are a bit screwed up, but Taylor breaks past the surfaces and lets us into their lives, sometimes (as in “In My Heart I Am Already Gone” or “The New Life”) showing how mental and emotional blind spots can steer us down a path with devastating consequence. For his “Selling Shorts” essay, Taylor has chosen a similar story, the impact of which he himself didn’t quite recognize at first.

One of my favorite story collections is The Wonders of the Invisible World, by my former teacher, David Gates. The ten stories in David’s book are riveting and dark. Their incisiveness—not for nothing from the Latin, to carve—is downright scary; they are brutal and wise. The protagonists of these stories are old and young, gay and straight, women and men; and yet, they all tend to share certain qualities: a level of sophistication (high), education (ditto), attitude (bad), and class (white-collar middle, striving for upper). The result is a very strange and exciting paradox: a group of discontinuous cross-cuts that somehow adds up to a panorama.

Of the ten stories in Wonders, the one I return to most frequently is the first one, “The Bad Thing,” which I’ve re-read (and also taught) enough times now that I’d like to try and quote the opening from memory: “He has never hit me, and only once or twice in our two years has he raised his voice in anger. Even in bed Steven is gentle. To a fault. Why, then, am I wary of him?” But I don’t want to talk about “The Bad Thing.” I want to tell you about a story called “The Crazy Thought,” a sly devastator, and my nomination for the book’s outstanding deep cut.

The things that make “The Crazy Thought” such a marvel are not elusive, exactly, but they are relatively easy to miss. I confess that the story didn’t make much of an impression on me the first few times around. In fact, I had forgotten about it entirely until I pulled Wonders off the shelf to double-check my quoting-from-memory of the opening of “The Bad Thing,” which is the story I thought I was going to be writing about when I started. (Oh, and if you were wondering, my attempt at recitation was close, but not quite cigar-worthy. The quote given above is the amended, which is to say the correct version.)

Flipping idly around, I stumbled onto “The Crazy Thought,” and for whatever reason decided to stop what I was doing and give it a re-read. (Perhaps I was drawn in by the slightly bizarre, though arguably easier-to-memorize opening line: “The year was round, a millstone turning slowly clockwise, and even on this Friday afternoon in August, Faye could feel it moving down toward Christmas.”) In any case, true to its title, I now can’t get “The Crazy Thought” out of my head.

28 July 2010 | selling shorts |

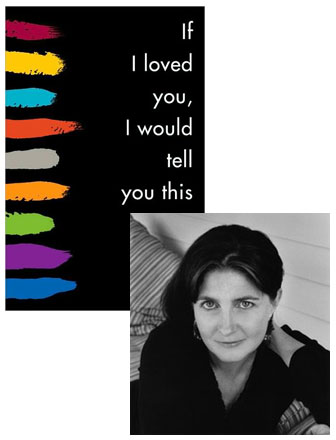

Robin Black & the Heart of “A Stone Woman”

In her guest essay, Robin Black recalls an early teacher’s description of her stories as “domestic angst,” and how she took it at the time as a minimization of her work. But when you read If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This, you come to both the accuracy of that brief phrase and the strengths it implies. Many of Black’s stories test the stress points of family relationships—husbands and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters—to the extreme, exerting pressures from within and without, and the results are emotionally raw and all too plausible. But, as she explains here, Black found inspiration for the persuasive realism of her most powerful stories in a fantastical source…

“At first, she did not think of stones.” So begins A.S. Byatt’s “A Stone Woman,” the story of a middle-aged daughter whose grief over her mother’s death transforms her into a being of myriad crystals, taking her from animal to mineral. From my very earliest reading, “A Stone Woman” entered my consciousness like news I had been waiting to hear. It became mine, a touchstone of sorts, in the way certain stories do for us all, which initially puzzled me because I haven’t ever been particularly attracted to magical stories. In fact, it’s fair to say that pretty much as soon as trees start talking or shoes begin walking on their own, I’m apt to tune out, more pushed away than swept away. Yet this story of transformation, with its evocation of Icelandic mythology and utter disregard for the prosaic rules of reality, seemed to have something, something essential, to tell me about my own work.

Trying to describe why you’re in love with a story is like trying to describe why you’re in love with anything, or anyone. In the end—says the woman who just claimed she doesn’t much like magic—there’s a magic that can’t and arguably shouldn’t be dissected. But maybe at the heart of all romances is the sensation of being able to be oneself, the vision of being loved as the person you think you are.

26 July 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.