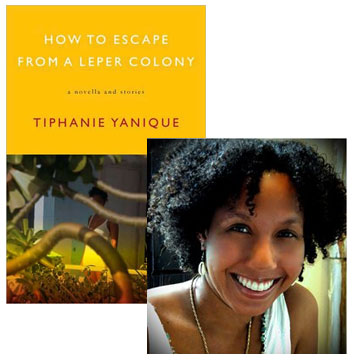

Tiphanie Yanique: The Tone of “Near-Extinct Birds”

Tonight, Tiphanie Yanique will be honored by the National Book Foundation as one of the “5 Under 35,” their annual tribute to a select group of promising young writers. She’s being recognized for the strength of How to Escape a Leper Colony, a fantastic collection of short stories that have already earned her an award from the Rona Jaffe Foundation as well. The breadth of Yanique’s storytelling is quite impressive—be sure to read the novella “The International House of Coffins,” which takes one encounter between three people and spins it in three very different directions—and, as she explains in this guest essay, that’s a quality that she consciously strived for. Don’t just take my word for it, though: You can read the title story, which won the Boston Review fiction prize, and if you like that, pick up the book and try the rest.

I love Ben Fountain’s Brief Encounters with Che Guevera for many reasons, but in particular because of something his collection does that many collections just don’t do: range. Range is one of the things I think a story collection can do more easily than a novel, and yet it’s something that collections often refrain from attempting. When a collection does attempt range often reviewers and readers just don’t know what to do with it.

By range, I mean that each story in a collection attempts something different. Fountain’s title story is mostly realist, about an Ameircan kid working in furniture delivery. Another story, “Fantasy for Eleven Fingers,” about a piano savant with an extra finger, is filled with fancy. Some stories are from inside of a culture as with “Bouki and the Cocaine,” told from the perspective of Haitian fisherman, and others are from the outside looking in, as with “Rêve Haitien,” told from the perspective of an American expat in Haiti. The stories are set in the Caribbean, South America, North America, Asia, Europe and Africa. While most of the stories are from the male perspective, there are standouts from women characters. Most of the stories are third person and from a white American perspective, but not all. This range is something I attempt in How to Escape from a Leper Colony in part because Fountain’s collection allowed me to know it could be successful. I didn’t realize how perilous this might be.

15 November 2010 | selling shorts |

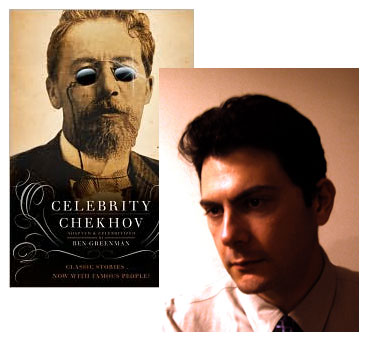

Ben Greenman Revisits Chekhov’s Barber

I’m a big fan of Ben Greenman, and I’ve been trying to get him to do a guest essay for the “Selling Shorts” series for a while. The arrival of his latest short story collection, Celebrity Chekhov, gives us the perfect opportunity. It’s a book with a fantastic, near-Barthelmian “gimmick”: Ben takes twenty-some stories by Anton Chekhov, removes the original characters, and replaces them with contemporary celebrities. (In the story he’s about to discuss, for example, the customer has become Billy Ray Cyrus.) The stories take on new meaning when readers invest them with their acquired attitudes towards the famous personages who’ve been added into the mix—but their original impact is not lost, as Ben explains while telling us about one of his favorites.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again: the others include Mary Robison, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, and Joy Williams. It’s not a long list, this set of regular destinations. There are dozens upon dozens of short-story writers I love, obviously,and nearly as many novelists, and I don’t mean any direspect to anyone else. What I mean, I think, is a certain specific kind of respect to these writers. There’s something in their work that I love stealing. For some of them, it’s the way they kick off their first paragraph. For some, it’s the way they draw characters. For some, it’s the way they manage dialogue. For some, it’s the rhythm, or the boldness of their language, or the clarity of their ideas.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again. This time, I came back to him holding a stick of dynamite, like in a Warner Bros. cartoon. Celebrity Chekhov comes after a series of books that people/critics have read as serious works of straight-faced literature, and because this one isn’t like the others, people are eager to classify it as humor. It isn’t, except in the sense that the original stories are. Sometimes, of course, Chekhov’s original stories were sad, and in those cases I tried to preserve the melancholy, or moral agony. Just as often, though, the originals are comic, perfectly assembled little clockworks of human folly.

Take “At the Barber’s,” an early Chekhov story and one of my favorites. It’s just a touch over 1,200 words, and relates two brief conversations that, between them, take maybe ten minutes. There is only one setting, the barbershop of the title, and only two characters: a young barber and an older customer, both men. But from that potentially claustrophobic formula Chekhov manages to produce a universal tale of hope, greed, and pride. It’s important to add that it’s also an entertainment: the ethical points are made, and made clearly, but the piece never sacrifices its sense of briskness or absurdity.

3 November 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.