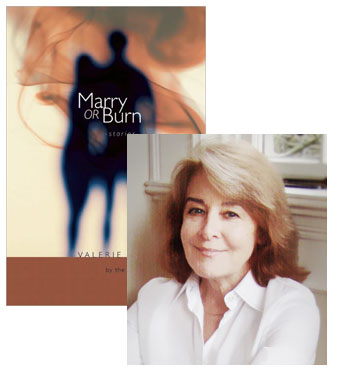

Valerie Trueblood & Welty’s Golden Apples

Valerie Trueblood is an expert at packing a short story with a rich backstory—the opening selections in her new collection, Marry or Burn, span years in their telling, and even stories like “Luck” or “Tom Thumb Wedding” that have a short time span on their surface contain dense pasts that weigh upon the unfolding present. But she doesn’t use the past to explain the present according to some obvious symbolic framework: It’s just that both are filled with incidents that offer implicit insights into her characters. In this essay, Trueblood tells us about another powerful example of the “show, don’t tell” principle of short story writing.

I have several editions of Eudora Welty’s story cycle The Golden Apples, the dearest to me a yellowed paperback, the one with the Bascove cover, small enough to be held open in one hand with the thumb on one half and the little finger on the other. Inside this small book is a world so dense, airy, lilting, lamenting, shocking, calming, and almost crazy with the sheer force of life that I can’t think of another book anything like it. Seven unruly stories are twisted up together, blown full of a sweet hilarity (“Whenever she opened the cabinet, the smell of new sheet music came out swift as an imprisoned spirit, like a pet coon”), and saturated with grief.

I wonder if Wallace Stevens read Welty’s stories. “Description,” he wrote, “is revelation.” I believe it’s in the short story—even more than in the poem—that we see what he meant.

“Why” is the territory of the novel, and the short story doesn’t dawdle there. It has left the path of reason and the outcomes dear to reason, and gone over into the land of the “what.” There, there’s absolutely no end to the things that can be seen to influence each other and to figure in someone’s fate. The short story is the place where these things get their due. My first awareness that they could be lifted into glory by a writer’s certainty that they were glorious came when I read The Golden Apples.

28 January 2011 | selling shorts |

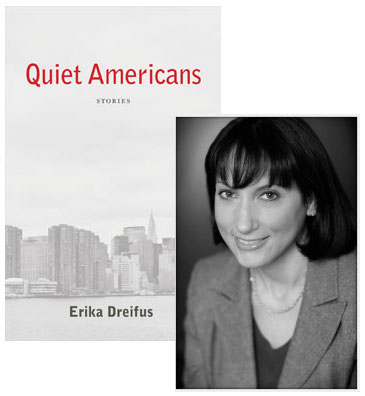

Erika Dreifus & Malamud’s “German Refugee”

I first met Erika Dreifus through her excellent blog Practicing Writing, and when I learned that she was coming out with a collection of short stories, I couldn’t wait to read it. Quiet Americans (which you can buy, signed, direct from the author) is a group of thematically connected stories about German-Jewish families who emigrated to the United States—several of the stories are directly connected, following four generations of the same family from the early 20th century to an attempt to revisit their homeland during the 1972 Olympics. These are powerful stories, with subtle turning points, and they mark a significant literary debut. In this guest essay, Erika explains how one short story, chosen to be among the last century’s finest, resonates with the stories that she has chosen to tell.

I owe my discovery of Bernard Malamud’s “The German Refugee” to The Best American Short Stories of the Century, which joined my bookshelf shortly after its release. And although I don’t normally use the word “frisson” in everyday conversation, it describes exactly what went through me when I saw the title of Malamud’s story in the anthology’s table of contents.

Reading this story as a writer, one notices a number of elements. First, there is the first-person narrator through whose eyes we learn of another character and his conflicts. Perhaps the most famous example of this technique is the Nick Carraway narrative of Jay Gatsby’s story. In “The German Refugee,” American Martin Goldberg recounts the tale of the eponymous “German Refugee,” an older German-Jewish man named Oskar Gassner, whom Martin describes as “the Berlin critic and journalist” who had fled Germany in the months after the Kristallnacht of November 1938. In those days, Martin tells us, he “made a little living” by tutoring such refugees in English, and the meat of the story recalls the summer of 1939, when Martin worked with Gassner in preparation for the latter’s delivery of a lecture in English.

Then, too, for anyone who focuses on language, this story yields rich rewards. For instance, one sees how a character—in this case, a refugee character—gains definition through speech: “‘Zis heat,’ he muttered…. ‘Impozzible. I do not know such heat.’ It was bad enough for me but terrible for him. He had difficulty breathing.” Language itself is almost a minor character in this story, one who inspires tremendous anguish. As Martin reveals: “To many of these people, articulate as they were, the great loss was the loss of language—that they could no longer say what was in them to say. They could, of course, manage to communicate, but just to communicate was frustrating. As Karl Otto Alp, the ex-film star who became a buyer for Macy’s, put it years later, ‘I felt like a child, or worse, often like a moron. I am left with myself unexpressed. What I knew, indeed, what I am becomes to me a burden. My tongue hangs useless.'”

So I have writerly reasons to be interested in this Malamud tale. But undoubtedly it is because of two “German refugees” in my own life that I have revisited this story so often. Like Oskar Gassner, my father’s parents were Jews who emigrated from Germany in the late 1930s. In Oskar’s speech, I can hear theirs.

21 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.