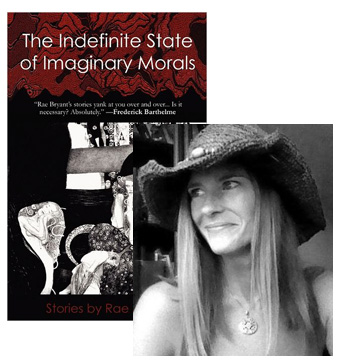

Rae Bryant Ponders Nabokov’s Signs & Symbols

Rae Bryant is coming to New York City later this week to launch her debut short story collection, The Indefinite State of Imaginary Morals, with a Saturday night reading at KGB Bar. In stories like “Postfeminist Zombie Assassins Wear Wonder Woman Underoos,” “Emperatriz de la Orilla del Río,” and “Featherbedding,” Bryant writes about desire with a dream-like quality: “If an average person thinks about sex several times a day,” she told The Nervous Breakdown, “then a single story without the convergence of gender and sex would be a dishonest slice of a natural day. I like natural days. I like to see them stretched and twisted and formed through surreal lenses.” It seems fitting, then, that she would be drawn to the stories, both short and long, of Nabokov…

Nabokov was a master at cutting his readers. His words are dexterous and sharp.

I came to Nabokov by way of Lolita, which may very well be my favorite novel, though tomorrow it will be McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. So today, Lolita.

One of the masteries in Nabokov’s stories, what I admire so much, is how smoothly the stories turn readers into accomplices. In Lolita, we begin cautiously, cringing at Humbert Humbert’s “Lolita… fire of my loins.” The lulling beauty of young Humbert’s language and his flashback affair with age-appropriate Annabel draws the reader into an acceptable narrative and set of mores. The subsequent transition to immorality is seamless. The crafting, perfection. The reader accepts Humbert as an emotionally stunted man, a child, and so accepts his replacement of the dead Annabel with a live and young Lo, who is something of his emotional equal. The moral cutting is almost imperceptible and before the reader fully realizes it, taboo has been severed from its leash and an addiction has formed for Humbert’s voice, his past, his self-delusions and the promise of a painful end. The reader sits quietly in the backseat of Humbert’s car and experiences the relationship unfold between him and his nymphet, one touch after another. Yes, reading Lolita is to be wounded. Nabokov takes his readers to dark places they swore they’d never go.

At times, it is easy to forget Humbert’s abuses as they’re narrated through his romanticized point of view. Further consider the socio-political layers, the undercurrent of commentary, the language play, double entendres and coded phrasings, and this all becomes really quite genius as much as it is vicious. The reader becomes a willing participant in this horror, an accomplice and confidante to Humbert’s actions, because one does not “watch” Lolita, one immerses.

Multi-faceted architecture recurs in all of Nabokov’s works, another being “Signs and Symbols,” re-titled “Symbols and Signs” by The New Yorker when they published the story in 1948. An unnamed son suffers from “referential mania” with an elaborate coding behavior by which he perceives everything around him as references to himself: “Everything is a cipher and of everything he is the theme.” The boy’s parents visit him on his birthday but are not able to see him in the sanitarium because the son has tried to kill himself again, and the nurses believe the parents would further agitate him. The day turns into a journey home, filled with images of a twitching bird, twitching hands, birds with human hands and feet, allusions to the son’s condition, artistic artifacts, Holocaustic history and perhaps the question, what is reality?

Like Lolita, “Signs and Symbols” delivers these artifacts by making the reader an accomplice, an archaeologist who excavates meanings along the way, realizing at the end, the question may not exist in the son’s condition but perhaps in the systems by which these conditions are catalogued. Nabokov doesn’t “tell” the reader to search socially, but rather, he uses the reader to formulate the hypothesis along the way—reality is not always the answer.

In June 2008, Mary Gaitskill gave a gorgeous online reading of “Symbols and Signs” at the New Yorker website. Interestingly, Gaitskill read from the Nabokov’s Dozen version of the story with his original title, rather than read the one in the magazine’s archives. In her post-reading discussion with Deborah Treisman, Gaitskill elaborated on the beauty and “tonalities” of the work while being somewhat resistant to discussing the coded language and layered narratives that are so often central to Nabokov’s stories. In Gaitskill’s discourse, is a sense of artistic agnosticism, a willingness to experience the story in its immediacy, linger in the constancy of searching without forcing a particular answer. Nabokov’s stories are good for this constancy of searching, as much as they are good for any other critical approach. For this reason, I return to Nabokov’s works often as a place of wonderment, morality and tireless questioning.

20 July 2011 | selling shorts |

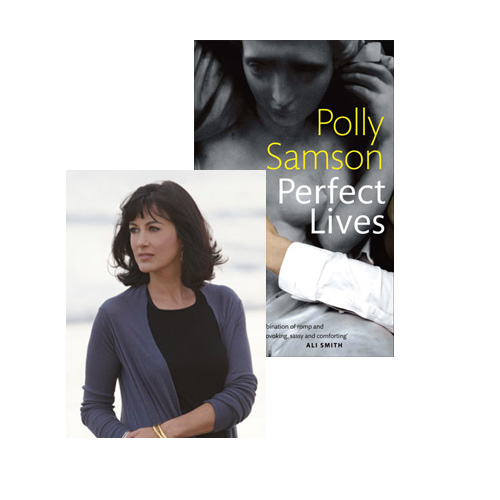

Polly Samson: Haunted by “The Apple Tree”

Polly Samson links the stories in Perfect Lives, her second collection, by overlapping characters in the same community—the family featured in one story will be the last clients of the piano tuner in the next story; his first client will be a friend to the unnamed woman whose first-person account of her marriage and family life is revisited several times. (This narrator also has an intense love of photography, drawing upon Samson’s personal passions). Some of her characters are just millimeters away from a breakdown, others are already behaving quite erratically, but a few have managed to carve out moments of comfort and passion; they all, however, tend to be at best tangentially aware of the dramas being played out around them. Samson has written the introduction to a collection of some of Daphne du Maurier’s earliest work, The Doll and Other Stories, so it makes sense that she would invoke du Maurier for this “Selling Shorts” essay—and the nervous energy in so many of her characters makes the choice even more apt.

As a child in London, I suffered so badly from nightmares that my mother took me to the doctor. I remember clearly the doctor in half moon glasses solemnly writing out a prescription for warm milk at bedtime, and yet I remember very little about the nightmares themselves: just a feeling of darkness, and trying to run, of gnarled roots and branches closing in around my head.

I stopped having bad dreams when we moved to Cornwall when I was eight. My suddenly peaceful sleep was odd, considering that we now lived in an old granite vicarage said to be haunted by a murderess and which was situated beside an ancient graveyard from which our terrier would bring the occasional femur. It wasn’t far from Fowey, where Corwall’s greatest novelist—Daphne du Maurier—lived and work, and this was real du Maurier country: open moors, windswept, sparsely populated… As I headed into my teens, I found I shared du Maurier’s passion for this wild landscape over which my own imagination had been freed to roam. I lost myself in her novels and slept peacefully at night.

I don’t know why I didn’t read her short stories until much later. I don’t think I ever came across them at the time; perhaps they weren’t even in print. I remember being surprised that two films that had truly terrified me—each causing a resurgence of nightmares—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now were, in fact, based on du Maurier short stories.

As terrifying as I found the movies, I found that The Birds and Don’t Look Now wound the tension even tighter on the page than on the screen; du Maurier can do atmosphere and menace like no one else, and her short stories make my pulse race faster than her novels. In the smaller space, she hasn’t had to think too much about pace or form, so the stories seem more instinctive. In the more concentrated form, she is able to tap into fears that are so deeply subconscious you don’t even know that they are yours.

20 May 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.