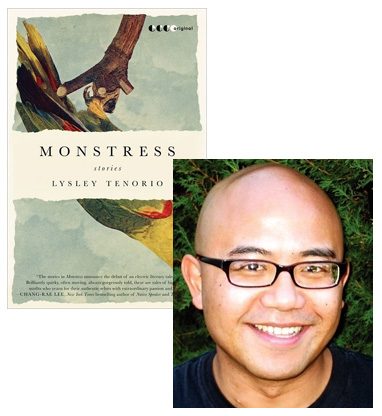

Lysley Tenorio On Dying & Character Development

The stories in Lysley Tenorio’s Monstress cover a wide range of Filipino and Filipino-American experiences, from a teen’s confused efforts to help his Imelda-fixated uncle exact revenge against the Beatles for a perceived offense during their 1960s visit to Manila to two elderly men who’ve spent their adult lives together in San Francisco’s International Hotel, from an actress in grade-Z monster movies who follows her husband on a desperate trip to Hollywood and discovers an unforeseen opportunity to a contemporary young man struggling to come to terms with the death of his transsexual younger sibling. There’s also a fantastic story, “Superassassin,” in which a teenage boy schemes to exact vicious revenge against his tormentors while caught up in his comic book-inspired fantasies. Tenorio comes by his portrayal of comics fandom honestly, as we’ll discover in this essay, and it’s also played an interesting role in shaping his literary vision.

I loved a girl once. For almost ten years. She was kind and selfless, a girl of unmatched courage, stronger than anyone I knew.

Then, when I was twelve years old, she died.

Her name was Kara. Kara Zor-el.

You might know her as Supergirl.

It was 1985. DC Comics had released Crisis On Infinite Earths, a 12-part series designed to streamline the overstuffed and overcomplicated DC Universe of multiple and parallel earths. In issue #7, Supergirl squares off against the Anti-Monitor, an all-powerful ruler of an Anti-Matter universe determined to destroy our own. It was a battle for the ages: just as the Anti-Monitor is about to kill her cousin, Superman, Supergirl swoops in, pummels the crap out of the Anti-Monitor, but on the verge of victory, she makes one fatal mistake: she looks away. With that, the Anti-Monitor unleashes his deadliest force-blast, killing her. But for the meantime, Supergirl has managed to disable his weapons, temporarily foiling his plans. “Thank heavens…” Supergirl says in her final breaths, “…the worlds have a chance to live…” Then, in Superman’s arms, she dies.

I finished reading it inside the comic book store, paid for it, then went with my sister to Pizza Hut. But I couldn’t eat. I felt numb. I felt dizzy. Across the table, my sister looked at me like I was an idiot, mourning a make-believe character, a girl of two dimensions. But I knew: This was grief. It had to be.

Lately, there has been a lot of dying in my classroom. In my freshmen fiction workshop, my students have been killing off their characters with cancer, brain tumors, car crashes, hit men, and comas from which they never awake. And they render these deaths with a gusto that’s admirable: they know the effect they want, and they go for broke, indulging every tear, breakdown, and bloodspurt. But for the most part, it doesn’t work. Reading these stories, we might find something recognizable or familiar (“Someone died at my high school too!”), but at most we understand these spectacular deaths, but we don’t feel them.

The problem isn’t necessarily the death itself; death is an intriguing and potent subject for fiction. The problem is the lack of life preceding it, the absence of that singular life force that every fictional character must possess in order to earn the right to die. We can only feel so much from the summarized life.

When I read these stories, I want to tell them about Supergirl. I was a living witness to the destruction of her home, Argo City (a sort of final city-remnant of Krypton, which exploded years before). I knew her as Linda Lee, the alias she assumed at the Midvale Orphanage, and that she had two pets: Comet the Superhorse and Streaky the Supercat. And when she wasn’t Supergirl, when she was simply Linda, she had the ambition and aimlessness of young adulthood—she was a high school counselor one day, an aspiring TV reporter the next, a soap opera actress soon after. I knew her powers and weaknesses, her losses and loves, her allies and nemeses, her victories and defeats. All that super-living, measured against a gloriously epic death scene. No wonder it worked. No wonder I mourned her.

6 February 2012 | selling shorts |

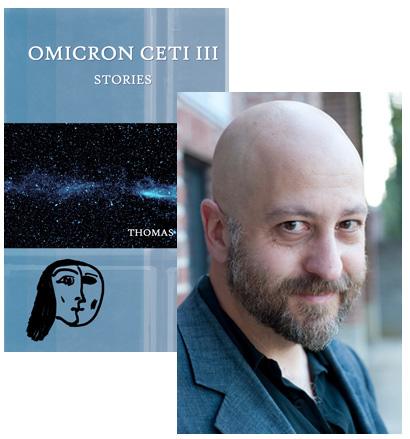

Thomas Balazs: The Humor of “People Like Us”

The protagonists of the short stories in Omicron Ceti III are a pretty screwed-up bunch: There’s the high school senior who takes his frustration about his sexual attractions out on his English teacher, the young mental patient who finds one of his few forms of emotional solace in an old Star Trek episode, the art professor whose sexual addiction threatens to drive his family into debt. Thomas P. Balázs gets inside these characters’ heads and latches onto those moments in which they recognize that things have gotten well out of hand, but they can’t quite see the way out… and yet, whether it’s out of perseverance or perversity, they refuse to give in to despair. In this essay, Balázs talks about a classic Lorrie Moore short story that may help you understand a bit more about the tone you’ll find in his own work—which, by the way, you can hear online.

I’m prone to depression, and at its worst, my writing reflects that disposition toward self-obsession, self-loathing, to a dreary black outlook that threatens to turn my prose into the kind of dull, inward-looking meditations that bore even me as I write. A good therapist and a good antidepressant can do much to alleviate such a temperament in daily life, but when it comes to writing, I’ve found only one truly effective treatment—humor. And, as a result, most of my work tends to exhibit a comic tinge even when I’m not trying to be funny because practically the only way I can keep my fingers moving on the keyboard is by poking fun at the very problems that make me want to shut off my screen and go back to bed.

And it’s probably for the same reason that the writers I most admire, Lorrie Moore, David Foster Wallace, Philip Roth, Tim O’Brien, have a gift for comedy and in particular for comedy infused by pain, what we sometimes call black comedy.

The link between humor and pain is undeniable, and writers know this instinctually. It’s no coincidence that the masterpiece of a writer who was so depressed he hung himself on his patio is titled Infinite Jest. Wallace, I’m sure, used humor as a tool to keep the demons at bay, or at least manage them in his fiction. Sadly it wasn’t enough for his non-writing life.

One of the best, and for me most influential, examples of humor as a tool for staving off despair in fiction lies in Lorrie Moore’s short story “People Like Us Are the Only People Here.†This story, which first appeared in The New Yorker, tells the tale of a mother (simply described as “the Motherâ€) coping with her toddler’s diagnosis and treatment of kidney cancer. Funny stuff, right? Certainly, this is not a laugh-out-loud piece, but it is funny in a weird kind of way.

Take the opening paragraphs when the Mother discovers blood in her boy’s diaper. She describes the clot as “a tiny mouse heart packed in snow†with a “khaki-colored vein‗a little repulsive, yes, but such an unexpected combination of images may well provoke an uncomfortable smile. The Mother tries to deny the blood clot’s reality, speculating her child found it and put it in his diaper for “demented baby reasons.†And when she calls the hospital and tells them what she’s found and is directed to come in right away, she remarks “Such pleasantly instant service! Just say ‘blood.’ Just say ‘diaper.’ Look what you get!†There’s pain and anger here, but also a good deal of, to paraphrase Moore herself, collateral humor.

The rest of the story tells of the various tests and procedures both baby and Mother are subjected to, punctuated with oddball moments such as a lounge in the child’s cancer ward endowed by the eccentric 1960s one-hit wonder Tiny Tim or the moment when the Mother (who is a writer), wonders, shortly after getting her child’s diagnosis, why the attending doctor bought the paperback, instead of the hardcover edition, of one of her books. The humor is subtle and unsettling, pleasurable and painful at once. Just the sort of thing I like.

I also like it because it “cuts close to the bone.†Although she has been private about the origins of this story, it’s commonly known that Lorrie Moore’s child (who apparently survived) suffered from some manner of kidney disease. So maybe the humor doesn’t just help the writing but the writer as well. Most of the comic writers I admire write close to the bone. Roth and O’Brien both go so far as to name troubled fictional protagonists after themselves. The disturbed genius and tennis prodigy of Infinite Jest is surely not a far cry from Wallace’s own adolescent self.

It may be for this same reason that I’m less enamored of more satirical comic writers such as George Saunders or T.C. Boyle, because the object of their ridicule is typically at some comfortable distance from themselves. I guess I find it funnier to hear someone talking about themselves slipping on a banana than to hear their description of a third party doing the same. Sure, there are plenty of deserving targets for satire, but I generally get more out of reading writers who use humor to explore their own human shortcomings, writers who explore their own trauma and depression and pain, whose comedic target is primarily people like us.

1 February 2012 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.