How Alethea Black Fell in Love with “Natasha”

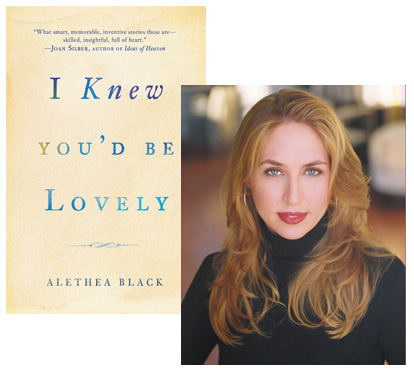

I’ve been friends with Alethea Black for a couple years now, and I’ve had the pleasure of reading some of the stories in her debut collection, I Knew You’d Be Lovely, when they were first appearing in literary magazines. In recent months, she’s been taking part in pretty awesome events, like the WordTheatre reading at Soho House that’s coming up on March 4, 2012, where one of her stories will be read by Maggie Siff (of TV’s Mad Men and Sons of Anarchy). In this guest essay, Alethea talks about a David Bezmozgis short story that showed her on just how many levels great fiction can move us.

At Thanksgiving in 1994, my sister Ashley gave me an orange paperback volume of The Best American Short Stories, edited that year by Tobias Wolff; she didn’t know that she was changing my life. Unlike the staid, obligatory short stories I’d been assigned in high school, these contemporary tales struck me as often funny and fresh and always absurdly, fiercely true. Before that, I’d had little exposure to writing that was simultaneously playful and profound, as eloquent as it was informal. It was like discovering a bootleg Bible that was full of jokes. And it made me want to be a writer.

I spent the following ten years reading and studying contemporary short stories, in pursuit of a sort of home-school MFA—although I don’t think I realized that’s what I was doing at the time. A decade after my Best American initiation, Michael Chabon’s introduction to the 2005 volume expressed what I’d learned. “Entertainment has a bad name. Serious people, some of whom write short stories, learn to mistrust and even to revile it. The word wears spandex, pasties, a leisure suit studded with blinking lights… Entertainment, in short… is bad for you—bad for your heart, your arteries, your mind, your soul.†He goes on to say—in a wildly amusing way—that the problem lies not in stories that amuse, but in our impoverished respect for the power of amusement. When I read that introduction, I was still two years away from publishing my first short story, and six years away from publishing my first book. But Chabon’s words became a call that I would try to answer in my own work.

The stories in Chabon’s edition of Best American bend lithely beneath the limbo bar of his introduction, and include some miraculous feats of entertainment: Tom Bissell’s “Death Defier,†Joy Williams’s “The Girls,†George Saunders’s “Bohemians.†But the story that inspired me most is David Bezmozgis’s “Natasha,†about a young Soviet Jewish immigrant’s first experiences with sex and betrayal. I love its energy (opening line: “When I was sixteen, I was high most of the timeâ€); its easy yet inventive voice (“I thought it had to do with the forbidden. The attraction to the forbidden in the forbidden. The forbiddenestâ€); and its humor (“She dropped down into one of the two velour beanbag chairs in front of the television. Chairs that I had been earnestly and consistently humping since the age of twelveâ€). I love the way it makes its own rules—Bezmozgis introduces his characters’ speech with em-dashes, forgoing quotation marks and dialog tags—and fearlessly encompasses masturbation, pornography, Nietzsche, Bob Marley, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Led Zeppelin, and Bizet’s Carmen. I love that it has a character named Rufus.

Any fan of screwball comedies or Alfred Hitchcock thrillers knows that just because something is exhilarating and enjoyable doesn’t mean it can’t also be edifying and true. What’s more entertaining than flat-out, buck-naked genius? Kafka described a book as an axe for the frozen sea within, and Chabon names the breaking pleasure. “Because when the axe bites the ice, you feel an answering throb of delight all the way from your hands to your shoulders, and the blade tolls like a bell for miles.†In my forty-two years on the planet, I’ve yet to find anything with a greater capacity to curl my toes and widen my mind and upend my heart than a perfectly-hewn short story. Then again, maybe I don’t get out enough.

2 March 2012 | selling shorts |

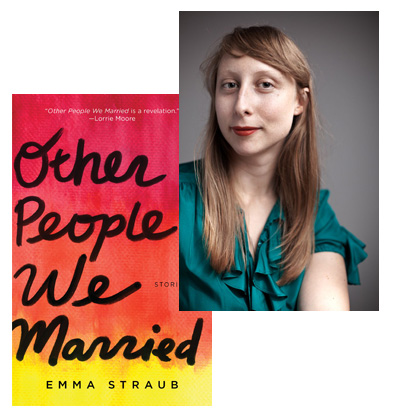

Emma Straub’s First Kisses

In early 2011, Emma Straub released a collection of wonderful short stories through the book publishing arm of the online literary magazine Five Chapters. A lot of people fell in love with those stories over the following months—one of them was Megan Lynch, an editor at Riverhead Books. Lynch was so impressed after hearing Straub read at a bookstore event that she didn’t just buy a copy of the book, she bought the book… and now, almost a year to the date after its original publication, Other People We Married has an even greater opportunity to impress itself upon readers. (Riverhead will also be publishing Straub’s first novel later in 2012.) Sometimes it’s hard for a “Selling Shorts” to pick just one story to write about, and that’s how it was for Straub. She’s got a list of great stories that helped awaken her to the possibility of writing in this genre, and she’s still discovering amazing stories by new writers. And I won’t be surprised if, some day, another writer comes along who talks about stories like “Fly-Over State” or “Puttanesca” or “Marjorie and the Birds” the way she talks about her favorites.

I didn’t write a short story until I was twenty-six, and already in graduate school. Up until then, I’d fancied myself a novelist and a poet. My writing could either be plot-driven or language and image-centered, with character-driven human emotion itself falling somewhere in the chasm between them.

People may love to mock the proliferation of MFA programs, but I can say without hesitation that my MFA experience, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, introduced me to the subtlety, epiphanies, and to the millions of minute shifts in feeling. Of course, I wasn’t actually being introduced to these concepts, not having been born a robot, but I was given a much better language for understanding and describing them.

Some of the stories I read during those first six months or so will always stay with me, no matter how many stories I read and love. I suppose it’s something like remembering your first kiss, even though you’ve been kissed better a thousand times since. They include Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” and Toni Cade Bambara’s “Raymond’s Run.” They include Michael Cunningham’s “White Angel,” and Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs.” They include Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” and Lorrie Moore’s “You’re Ugly, Too.” Sometimes your first kiss is an epic one. I went on to read famous stories and obscure ones, anthologized classics and stories by my friends. I was obsessed.

And some obsessions, like kissing, never go away. This last year I fell hard for stories by Stuart Nadler, and Dan Chaon, and Caitlin Horrocks, and Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Adam Wilson. Short stories make me feel, even more than poems or novels, that some things are still possible: that there are other languages out there for me to learn, other geographies to traverse. And when I get there, to the other side of some rocky shore, I will be able to tell you all about it.

8 February 2012 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.