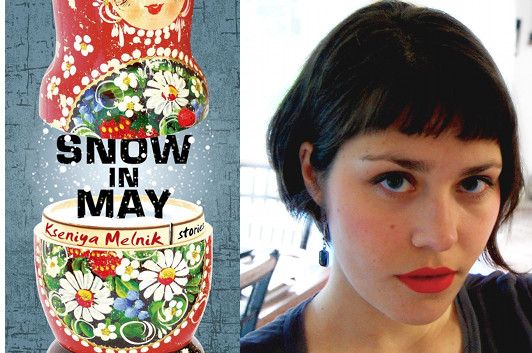

Kseniya Melnik and the Long Short Story

photo via Kseniya Melnik

Kseniya Melnik was born in the northeastern Russian city of Magadan, which also serves as a home base for the characters in the stories that make up Snow in May, her debut collection. Their experiences span late Soviet and post-Soviet history; she jumps back and forth over decades from one to the next, but it’s not jarring, because each story is captivating in its own way, immersing us in an equally compelling interior drama. Another side effect of that immersion is that you won’t notice how long some of these stories are—for, as she explains in this essay, Melnik has learned to give her stories the space they need, and we’re the ones who benefit from it.

Ever since I became serious about writing stories, my drafts have consistently come in at over what is considered the page limit for the standard American short story—twenty-five pages, or about 7,000 words. This seems to be the magic number, at least according to most contest rules, literary journal submission guidelines, syllabi of college creative writing workshops, and MFA application requirements. The stories in The New Yorker mostly adhere to that length or less, and the compact stories of Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff, John Updike, and Lorrie Moore still wield great influence around the workshop tables of America.

For many years, I chopped my stories down to bare bones to submit to contests and journals only to see the drafts grow back all that meat (and some descriptive fat) in the next revision. Even in the MFA workshops, where the submission guidelines were expanded to “as long as it needs to be,” my drafts were the longest in the class.

I always turned in my forty-pagers with a plea for help to choose what to cut. Usually, my classmates’ suggestions were superficial—fifty words here, a hundred there. To fit into that key length of twenty-five pages, I would have to re-imagine the scope of the story, cut scenes, whittle down characters. An occasional recommendation was: write a novel out of it! But I was convinced that what I had on my hands were definitely short stories and not summaries of novels or even compressed novellas.

19 May 2014 | selling shorts |

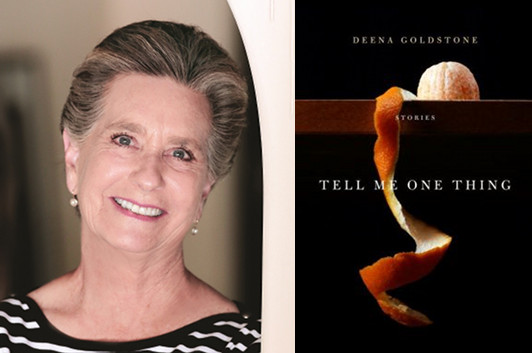

Deena Goldstone on Amy Bloom’s “Sleepwalking”

photo: Patricia Williams

Readers of a certain age (my age and thereabouts, in fact) may recall the TV-movie A Bunny’s Tale, in which Kirstie Alley plays a young Gloria Steinem, going undercover as a server at the Playboy Club. That film was one of the early screenwriting credits of Deena Goldstone, whose debut short story collection, Tell Me One Thing, has just come out. In this guest essay, Goldstone talks about the valuable lesson that one of Amy Bloom’s stories provided as she was making the transition from screenplay to short fiction.

Amy Bloom showed me how to write about grief without ever mentioning the word. Many months before I even contemplated writing my first short story, I read one of hers, “Sleepwalking.” It was in the days when I considered myself a working screenwriter.

I was at the point in my writing life, thirty years in, when I felt I had really mastered my craft—one that is precise and structured and disciplined. But just as I reached that level of confidence, I also began to bump up against the limitations of the form. There’s little place for lyricism in screenwriting or long descriptive paragraphs or internal monologues. Characters’ emotional states have to be inferred from dialogue and behavior. I found myself reading voraciously in other forms—short stories, novels—without quite understanding that I was schooling myself in another way to write.

Amy Bloom became my teacher early on. “Sleepwalking” is about a recent widow, Julia, whose husband, Lionel, a musician, has died of causes we don’t know and never learn. Bloom’s focus is on the small family he has left behind: Julia, his third wife, Lionel, Jr, nineteen, his son from his second marriage, Buster, his young son with Julia, and Julia’s mother-in-law, Ruth. It is a story about how these people get through the raw and painful days right after the funeral.

What stopped me in my tracks when I read the story was how much Bloom can tell us in a single sentence. Here is a description of her difficult mother-in-law and of the man her husband was when she married him—Ruth “hadn’t raised Lionel to be a good husband; she’d raised him to be a warrior, a god, a genius surrounded by courtiers. But I married him anyway, when he was too old to be a warrior, too tired to be a god, and smart enough to know the limits of his talent.â€

And here is the sentence describing the first meeting of Julia and her future stepson: “When my husband brought his son to meet me the first time, I looked into those wary eyes, hope pouring out of them despite himself, and I knew that I had found someone else to love.â€

Now we know everything we need to know about the past—who Lionel was when Julia married him and about the, guarded, hopeful boy she raised and loved as he needed to be loved. Amy Bloom gives us the “backstory,†as we say in screenwriting, in three amazing sentences.

5 May 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.