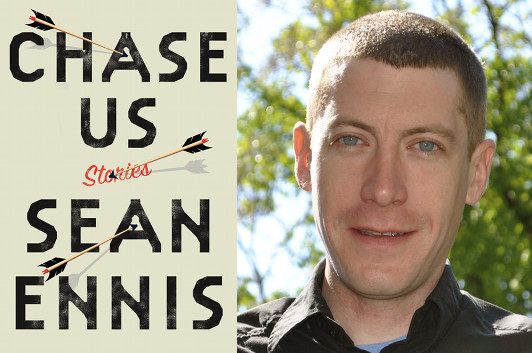

Sean Ennis: An Unsettling “Orientation”

photo: Claire Mischker

The Philadelphia of Sean Ennis’s Chase Us is a surreal, violent territory, one that the narrator navigates precariously from one story to the next. The collection isn’t so much a novel in stories, I think, as a series of variations on a theme; although the setting and the characters carry over from one story to the next, it doesn’t seem—at least initially—that a linear narrative carries over with them.) Once you’ve read a few of Ennis’s stories, you might be able to see what drew him to the Daniel Orozco story he’s written about in this guest essay…

I’ve always liked stories about work. Not only is it the place where most of us spend the majority of our time, but for a fiction writer, it seems like the ideal setting to create drama. Unless you’re very lucky, work is a place where you are often forced to interact with people you’d otherwise avoid.

Daniel Orozco’s “Orientation” takes the form of a dramatic monologue given by a middle manager introducing a new employee to the company. The specific work that this office engages in is never really mentioned, but we quickly get the sense that the audience for this speech has not exactly landed the ideal job.

In a lesser writer’s hands, it is easy to imagine this piece functioning as a one-note gag, riffing on the banal idea that office life is alienating and unfulfilling. No doubt, that idea is in Orozco’s story, but he’s mainly done with it after the first page. Instead, what follows is a list of an increasingly terrifying cast of characters who inhabit this particular office, brutally dissected by the narrator who speaks of the rules of the coffee pool and the sadomasochistic habits of his coworkers with an equally detached tone.

What I love and admire about this story is the way that both form and content are working in tandem. First, form. As a dramatic monologue, it places the reader in the position of the new hire being oriented, evaluating his/her new job for the first time. By the end it leaves the reader with a choice—decide to return for the second day on the job or run away screaming. I’m not suggesting that the story is so immersive that the reader actually forgets where they really stand—this isn’t a Disney ride. But it does mimic the question lots of people have about their job when they leave it for the day: will I come back tomorrow? While most great stories pose a question to the reader on some level, this seems much more explicit.

8 June 2014 | selling shorts |

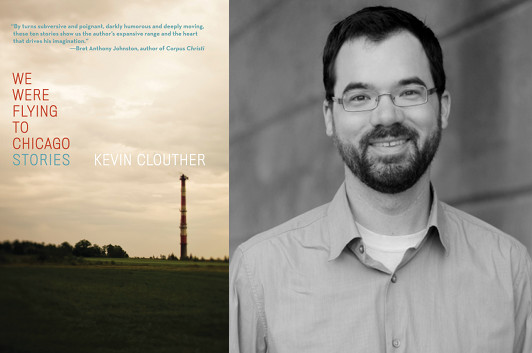

Kevin Clouther & the Vision of Chekhov

photo via Black Balloon Publishing

I’ve been dipping in and out of the stories in Kevin Clouther’s debut collection, We Were Flying to Chicago, over this long weekend, and they’re fantastic. In the title story, Clouther takes on the collective consciousness of a group of airplane passengers, from the long stretch of time they’re stuck on the runway waiting to take off to the moment they finally reach Chicago—not their final destination, but they’ll be stuck there, too. It’s a portrait of boredom and frustration that escapes both in its own telling, approaching a kind of abstraction even in its particular details. In this guest essay, Clouther considers Anton Chekhov’s own eye for detail, and the vividness of his stories.

I rarely think about Anton Chekhov’s stories while I’m writing, though I often think about them as I’m living, which ought to be higher praise. There is a celebration of existence in his stories that is more than earnest or unembarrassed—it’s triumphant, as if the writer is grabbing the reader by both arms and insisting this person lift his or her grubby head to look, if only for a moment, at the world as it actually presents itself. Here is Chekhov (translated beautifully, as always, by Pevear and Volokhonsky) in “The Man in a Case”:

It was already midnight. To the right the whole village was visible, the long street stretching into the distance a good three miles. Everything was sunk in a hushed, deep sleep; not a movement, not a sound, it was hard to believe that nature could be so hushed. When you see a wide village street on a moonlit night, with its cottage, haystacks, sleeping willows, your own soul becomes hushed; in that peace, hiding from toil, care, and grief in the shadows of the night, it turns meek, mournful, beautiful, and it seems that the stars, too, look down on it tenderly and with feeling, and there is no more evil on earth, and all is well.

I forgot that I ever looked at a street like this until Chekhov reminded me: I love when writers do that. The transition from the third person to the second is a gesture I would be reluctant to make, but Chekhov does it so readily, and with such confidence, that I trust there is something universal here. The last endless sentence does so many things I wouldn’t dare, like the accumulation of abstract adjectives—”meek, mournful, beautiful”—and frank consideration of “evil on earth.” He doesn’t shy from discussing the soul. Committing the pathetic fallacy doesn’t bother him, either.

It all reminds me of the last four lines of “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802,” a gem from the other end of the same century (would Chekhov have read Wordsworth?):

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

26 May 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.