Helen Marshall’s Two Short Story Mentors

photo: via ChiZine

Gifts for the One Who Comes After, the second collection by Canadian author Helen Marshall, is full of dark, unsettling stories. Not horror, precisely, although they’re certainly unworldly, in a way that enables certain moments to take up residence inside your head long after you’ve set the book aside. Heck, “All My Love, A Fishhook isn’t even a particularly supernatural story, or at least you can read it that way, and it’s still disturbing…

As I was reading, I was reminded of some of the episodes from the original Twilight Zone, ones like “It’s a Good Life” or “Nothing in the Dark,” though with greater subtlety. (Look, I love “It’s a Good Life” as much as anyone, but subtle it ain’t.) In this guest post, Marshall tells us about two writers who’ve helped shape her voice—one of whom I’ve already read with great pleasure, which inclines me to track the other down at the first opportunity.

There are stories that, the first time you read them, are so gorgeous, so powerful, and so magical that they remind you that fiction exists for the sole purpose of learning what you can get away with. There are two such experiences that have been etched into my mind. The first was when I picked up Robert Shearman’s collection Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical. The cover is sweetly unassuming: three miniature animal-headed girls in tartan skirts stand clustered on one side while a lone figure, dressed identically, but with a sleekly insectoid face of a fly slumps on the other side. It doesn’t prepare you. Not at all. Inside are a host of darkly comic stories that weave together the surreal and the achingly human. Reading these stories is like hugging a teddy bear only to discover someone has stuffed it full of razorblades. It might feel good at first, but you don’t realize until you’re bleeding out how deeply you’ve been cut.

One of my favourite among the stories is “Pang”—about a middle-aged man who lives in a universe where lovers literally hand each other their hearts in a Tupperware container. Facing the dissolution of his marriage, our hero desperately searches the house for his lover’s heart only to discover he has carelessly misplaced it while she has taken excellent care of his. As we follow his quest to substitute a pig’s heart from the local butcher shop, we come to understand his growing coldness and the possible reasons for the breakdown of their relationship. It’s a beautiful example of a story which blasts past the absurdism to find something touching and real.

Another story which picks up similar themes is “One Last Song,” which follows the trajectory of a young boy’s career as he manages to write one of the world’s greatest love songs—only to find in his later years that he can never quite live up to the early hype. These are stories that make you hurt in the best possible way, and they showed me that there’s a power in charming your audience that can be made devastating in the right hands.

11 October 2014 | selling shorts |

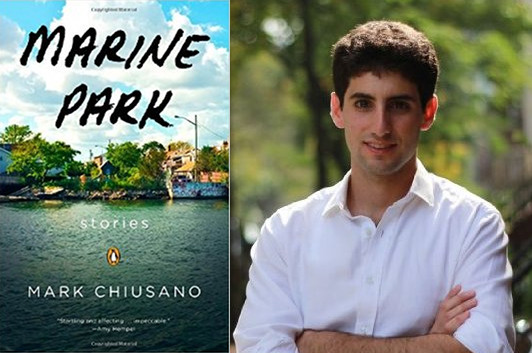

Mark Chiusano: A Year of “Moral Disorder”

ohoto: Charlotte Alter

Though the initial stories in Marine Park are focused on a boy and his brother growing up in the far end of Brooklyn, near the park that gives the collection its name, Mark Chiusano has plenty of other characters to introduce us to, like the couple whose romance rises and falls in the shadow of the Manhattan Project, or the chain of people linked by their sexual histories in 1970s New York City, or the old man who’s called upon to make one last smuggling run in the waters just off the outer boroughs. A few of these stories hint at the expansive time frames Chiusano talks about taking on in this essay—which discusses how to fit a great deal of time into a relatively small amount of prose.

For my day job I work at Vintage Books, where I’ve been working recently on a new project called Vintage Shorts, a program that pulls small sections from our old books for timely anniversaries or events in order to introduce readers to books they might have missed. Working on the project has had the side effect of introducing me to plenty of books I’ve missed. Two of them are Margaret Atwood’s story collection Moral Disorder and Geoffrey C. Ward’s biography of FDR, A First-Class Temperament. At the time I’d been trying to train myself in my own writing to lengthen out the time-frame in stories—many of the stories in Marine Park take place over days or hours, and I’d been experimenting with widening that scope. Reading A First-Class Temperament was an ideal way to increase my stamina, as it were.

Ward’s book is one of those fantastic, monumental, expansive and all-encompassing portraits of a historical figure—First-Class gets particularly close to Roosevelt as he struggles with polio, outlining the painstaking details of learning to “walk” again (he never would). Ward himself suffered from polio as a child and the attention to physical detail in his writing is palpable. In one of my favorite chapters from the book, Ward describes the two years in which Roosevelt goes from being a hermetic cripple to a political player once again, bookended on one side by his failed attempt to crutch himself into his old law office, and on the other by his journey down the aisle at the 1924 Democratic Convention to deliver the fabled Happy Warrior speech in support of Al Smith (“happy warrior,” a phrase from Wordsworth, wasn’t FDR’s idea, by the way: he thought it was far too poetic).

The chapter has the arc of a short story, with the repetition of attempts to walk at beginning and end, supported by a middle section in which FDR escapes on his houseboat Laroco for a spring cruise off the coast of Florida, a change of scenery that allows the reader to learn more about Roosevelt’s state of mind at the time (though Roosevelt hid it well from his houseboat guests, he sometimes couldn’t bring himself to leave his bed until noon) before the climactic events of the ending. Simple temporal section-openers like “At around eleven o’clock on Monday morning,” and “In February 1923, Franklin received from an old friend in England an elixir,” or “At around two-thirty in the afternoon of Monday, February 4, the Laroco anchored off St. Augustine,” are the bare-bones of nonfiction, but became useful in my fiction to help stories cover months and years.

28 July 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.