Read This: Skippy Dies

If you follow me on Twitter, there’s a good chance you know that I’m prone to crying (or nearly crying) at the movies—and not just at the expected stuff like Sounder or Rocky or Pan’s Labyrinth, but even big emotional scenes in films like Transformers leave me catching my breath. Books, though, not so much, so when I tell you that there’s a scene towards the end of Paul Murray’s new novel, Skippy Dies, where I was struggling to maintain my composure while reading on the New York subway, I hope you’ll understand just how powerful this novel is.

If you follow me on Twitter, there’s a good chance you know that I’m prone to crying (or nearly crying) at the movies—and not just at the expected stuff like Sounder or Rocky or Pan’s Labyrinth, but even big emotional scenes in films like Transformers leave me catching my breath. Books, though, not so much, so when I tell you that there’s a scene towards the end of Paul Murray’s new novel, Skippy Dies, where I was struggling to maintain my composure while reading on the New York subway, I hope you’ll understand just how powerful this novel is.

And the fantastic thing is: Just a few hundred pages earlier, I was fighting off a major case of the giggles on an airplane because there’s another scene in this book that is hysterically funny, that takes its joke and just keeps turning the dial a little bit further until… well, until I was about to explode, anyway. (Murray’s first novel, An Evening of Long Goodbyes, was equally side-splitting—based on the brilliant premise that you could still have a Bertie Wooster-like character running around the modern world… if he was completely delusional.) Balancing those two emotional extremes in the same novel could be a challenge, but Murray totally makes it work. He nails the ridiculousness of adolescence without ever losing sight of its deadly earnest and painfully raw aspects, and he brings equal honesty and empathy to his adult characters—except when he wants to make them cartoons, and then they’re brilliant cartoons.

The novel fulfills its titular promise in the darkly absurd opening scene, then backtracks to show what life was like for Daniel “Skippy” Juster at Seabrook, a Dublin boarding school, quickly expanding to absorb the perspective of several of his classmates and a few of his teachers (most importantly, in this context, Howard Fallon, a history teacher who also had a miserable time as a Seabrook student but can’t seem to break free of its gravitational pull). The story stays dark—but just when you think Murray’s about to make The Chocolate War seem optimistic, he adds another comedic twist, finally landing somewhere down the middle. Skippy Dies is easily one of my favorite novels of 2010; right now, I’m only trying to decide whether I like it better than David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, or whether I love them both equally.

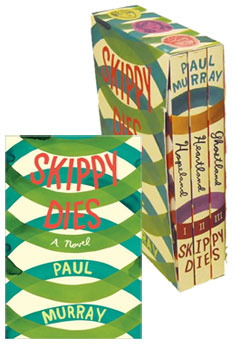

(Oh, and as you may have guessed from the picture, it’s being released simultaneously as a hardcover and a boxed set of three trade paperbacks, one for each of the main narrative arcs.)

10 September 2010 | read this |

Read This: Freedom & Fly Away Home

There’s a passage in Lev Grossman’s Time profile of Jonathan Franzen, addressing the literary accomplishment of Freedom, that caught my eye:

There’s a passage in Lev Grossman’s Time profile of Jonathan Franzen, addressing the literary accomplishment of Freedom, that caught my eye:

“A lot of literary fiction strikes a bargain with the reader: you suck up a certain amount of difficulty, of resistance and interpretive work and even boredom, and then you get the payoff. This arrangement, which feels necessary and permanent to us, is primarily a creation of the 20th century. Freedom works on something more akin to a 19th-century model, like Dickens or Tolstoy: characters you care about, a story that hooks you. Franzen has given up trying to impress with his scintillating prose… ‘It seems all the more imperative, nowadays, to fashion books that are compelling, because there is so much more distraction they have to resist,’ he says. ‘To me, now, to do something new is not to develop a form for the novel that has never been seen on earth before. It means to try to come to terms as a person and a citizen with what’s happening in the world now and to do it in some comprehensible, coherent way.'”

I don’t happen to agree that this “arrangement” is “necessary and permanent to us;” it certainly has never felt necessary to me, although I suppose there are some academics somewhere who might believe it so. But that’s a much larger issue, and we shall set aside for the moment. Instead, let’s focus on what Grossman and Franzen agree Franzen is doing in terms of readability and accessibility. You could almost read this as a sympathetic twist on a particularly caustic criticism of Franzen Ben Marcus wrote for Harper’s back in 2005:

“Jonathan Franzen has excelled most conspicuously at worrying about literature’s potential for mass entertainment… In reviews, essays, and lately even a short story, he has taken wild swings at some unlikely culprits in literature’s decreasing dominance. In the process he has also managed to gaslight writing’s alien artisans, those poorly named experimental writers with no sales, little review coverage, a small readership, and the collective cultural pull of an ant.

“Even while popular writing has quietly glided into the realm of the culturally elite, doling out its severe judgment of fiction that has not sold well, and we have entered a time when book sales and artistic merit can be neatly equated without much of a fuss, Franzen has argued that complex writing, as practiced by writers such as James Joyce and Samuel Beckett and their descendants, is being forced upon readers by powerful cultural institutions… and that this less approachable literature, or at least its esteemed reputation, is doing serious damage to the commercial prospects of the literary industry.”

I submit that the thing both Grossman and Marcus are describing is a key element of Franzen’s appeal to mainstream “literary” critics—he is just experimental enough as an novelist to tip the scales in favor of being viewed as “literary” rather than “commercial,” even though he is trafficking in, broadly speaking, the same type of domestic dramas you’ll find in, say, Jennifer Weiner’s Fly Away Home. Weiner’s narrative, about the ways in which a United States Senator’s confession of an adulterous relationship affects the lives of his wife and their two daughters, is presented in an almost completely linear fashion; there is some temporal backtracking and overlapping from one chapter to the next, as Weiner shifts perspectives, but she doesn’t call attention to it. Freedom, on the other hand, tells the story of one family’s disintegration and reconciliation (by means of events, including adulterous relationships, that are inflected with both political and cultural significance) as a series of sweeping narrative arcs with prolonged immersion in various characters’ perspectives—even, in the opening and closing sections, an ethereal “community” voice in which the most important events are told to the reader secondhand. Both novels thrive because their authors tell dramatic stories in an engrossing manner; one simply chooses to be more obviously virtuosic about it… but not so virtuosic as to call too much attention to his style.

7 September 2010 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.