Read This: The Iron Duke

There’s a section in Beyond Heaving Bosoms, Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan’s guide to romance fiction, that focuses on the history of the genre—specifically, on the moment when feminist readers (fans and editors both) rebelled against storylines in which the romantic hero essentially rapes his way into the heroine’s heart. It’s a chapter that I understood intellectually, but which I didn’t quite fully grasp because I’d come very late to the romance reading table, and I’d simply never seen any of those books… until Meljean Brook’s new steampunk fantasy, The Iron Duke.

There’s a section in Beyond Heaving Bosoms, Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan’s guide to romance fiction, that focuses on the history of the genre—specifically, on the moment when feminist readers (fans and editors both) rebelled against storylines in which the romantic hero essentially rapes his way into the heroine’s heart. It’s a chapter that I understood intellectually, but which I didn’t quite fully grasp because I’d come very late to the romance reading table, and I’d simply never seen any of those books… until Meljean Brook’s new steampunk fantasy, The Iron Duke.

This book came highly recommended from several romance fans who’d read advance copies, and it’s absolutely a fabulous story about a world in which England has only recently expelled a conquering “Horde” from Asia—a conquest been driven by the Horde’s nanotechnology which ended when Rhys, the eponymous “Iron Duke,” a pirate who’d commandeered a Royal Navy ship and used it to wreak havoc on the high seas, sailed up the Thames and destroyed their control tower. Now, somebody’s thrown a dead body on the Iron Duke’s estate, and he’s taken a liking to Mina Wentworth, the police inspector sent to investigate the death. So, naturally, he’s inclined to take what he wants. The dynamic is complex: Rhys repeatedly ignores Mina’s objections and advances their relationship to greater levels of phyiscal intimacy without her consent; on the other hand, he frequently feels remorse over those violations and tries to compensate for them. Meanwhile, Mina spends a lot of time telling herself she doesn’t want to be intimate with the Iron Duke, when the reality of the situation is more like she’s not emotionally ready for said intimacies, because of (a) the lingering psychological effects of having her body (including her sexuality) manipulated by the Horde’s nanoagents, and (b) her despised status within English society because of her half-Asian ancestry.

So while the intensity of the Iron Duke’s passion for Mina has its noble qualities—as when he decides that if he has to eradicate racial prejudice in England in order to make Mina feel comfortable, then that’s what he’ll do—some of the key “romantic” scenes in the novel have struck readers with whom I’ve spoken as disturbing. (Although other readers didn’t see them as rape scenes at all, describing them more sympathetically as examples of Rhys’ relentless determination.) But by no means would I suggest you shouldn’t read The Iron Duke. As I say, Brook respects the complexity of Rhys’ character; he does the things he does because that’s the way he knows how to operate, but he also reflects seriously on the consequences of his actions. Furthermore, the larger world in which the relationship between Rhys and Mina plays out—not to mention the intrigues behind that dead body that fell from the sky—is filled with fascinating alternate-historical details such as airships, a European landscape plagued with zombies, and mechanical kraken terrorizing the seas—and the promise of many more revelations in the inevitable sequels. It’s a novel that’s perfectly situated to cross over between romance and science fiction readers, and I expect people will be talking about it a lot in the weeks and months ahead.

18 October 2010 | read this |

Read This: Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu

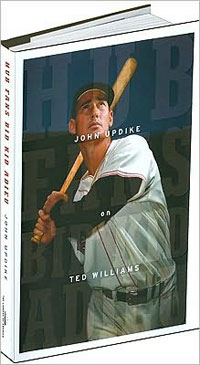

Fifty years ago, Ted Williams played his last major league baseball game; “on an impulse,” John Updike would recall years later, “I bought in for a few dollars… and the park was two-thirds empty. I was moved to write about the events of that game, in part because his departure, taking with it the heart of Boston baseball, had been so meagerly witnessed.” The essay Updike wrote, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” was published in The New Yorker a month later, and has been widely praised not only as one of the author’s best nonfiction works, but as one of the greatest pieces on baseball by any author. Earlier this year, it was republished in a commemorative Library of America edition, which is itself a fine bit of publishing. (Be sure to take off the Chip Kidd-designed dust jacket, even if only for a moment, to look upon the photograph reproduced on the book’s casing.)

Fifty years ago, Ted Williams played his last major league baseball game; “on an impulse,” John Updike would recall years later, “I bought in for a few dollars… and the park was two-thirds empty. I was moved to write about the events of that game, in part because his departure, taking with it the heart of Boston baseball, had been so meagerly witnessed.” The essay Updike wrote, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” was published in The New Yorker a month later, and has been widely praised not only as one of the author’s best nonfiction works, but as one of the greatest pieces on baseball by any author. Earlier this year, it was republished in a commemorative Library of America edition, which is itself a fine bit of publishing. (Be sure to take off the Chip Kidd-designed dust jacket, even if only for a moment, to look upon the photograph reproduced on the book’s casing.)

It’s not a long essay, but Updike managed to fit a lot of tribute into it—recounting not only Williams’ performance in his final appearance at Fenway Park, and the reactions of Updike’s fellow fans, but also the exemplary features of the slugger’s long career in Boston, as well as his contentious relationship with the local press. It is a partisan account, but not belligerent in its advocacy, and though a bit florid in spots (“After a prime so hassled and hobbled, Williams was granted by the relenting fates a golden twilight”), it holds up as one of the most genuine expressions of fandom I’ve had the good fortune to read.

28 September 2010 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.