Read This: Machine of Death

I love a good success story, and the self-published short story collection Machine of Death has a doozy: “When we picked a release date, we tried to aim for a day far from other major book releases—why invite more competition than we needed to?”the editors report. “Unfortunately we don’t know anything about publishing, and so missed the fact that a number of high-profile books also had official release dates of October 26.” Those included a new novel from John Grisham, Keith Richards’ memoir, and the new book from Glenn Beck. And, thanks to a highly effective online campaign in which those editors—Ryan North, David Malki, and Matthew Bennardo—reached out to their fans and asked them to buy the book on Amazon on its release date, they managed to become the #1 bestselling book at the site that day. That made Beck nuts enough to whine about how he’d been squeezed out of the championship that was his birthright by some left-wing culture of death. So, naturally, I ordered my own copy.

I love a good success story, and the self-published short story collection Machine of Death has a doozy: “When we picked a release date, we tried to aim for a day far from other major book releases—why invite more competition than we needed to?”the editors report. “Unfortunately we don’t know anything about publishing, and so missed the fact that a number of high-profile books also had official release dates of October 26.” Those included a new novel from John Grisham, Keith Richards’ memoir, and the new book from Glenn Beck. And, thanks to a highly effective online campaign in which those editors—Ryan North, David Malki, and Matthew Bennardo—reached out to their fans and asked them to buy the book on Amazon on its release date, they managed to become the #1 bestselling book at the site that day. That made Beck nuts enough to whine about how he’d been squeezed out of the championship that was his birthright by some left-wing culture of death. So, naturally, I ordered my own copy.

And now, the real question is: Is Machine of Death any good? I’m about a third of the way through, and I can tell you that I’m happily impressed. The premise is simple: There’s a machine that will tell you how (but not when) you are going to die, but the messages are not always straightforward: “Suicide,” for example, may not refer to your own attempts at self-annihilation. Each of the stories is titled with a death prediction; one of my favorite so far is “Torn Apart and Devoured by Lions,” in which Jeffrey C. Wells describes the enthusiasm with which an insurance salesman embraces his fate because, hey, it means he’s not going to be stuck in this cubicle for the rest of his life. (But there are also some seriously bleak tales here, like Bennardo’s “Starvation,” and more quietly disturbing stories like J. Jack Unrau’s “Firing Squad.”) I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the book whenever I can steal time away for a story or two, but based just on my initial impressions, these guys totally deserve all the success they’ve gotten and (if the momentum holds) will continue to enjoy.

9 November 2010 | read this |

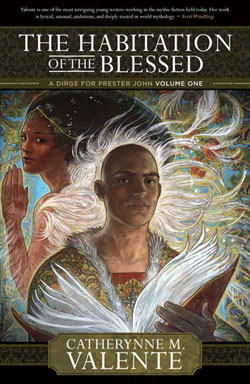

Read This: The Habitation of the Blessed

I have a new review in Shelf Awareness this morning, in which I wax enthusiastic over Catherynne M. Valente’s The Habitation of the Blessed, the first volume in a new trilogy called “A Dirge for Prester John,” recasting the medieval legend as a science fiction story.

I have a new review in Shelf Awareness this morning, in which I wax enthusiastic over Catherynne M. Valente’s The Habitation of the Blessed, the first volume in a new trilogy called “A Dirge for Prester John,” recasting the medieval legend as a science fiction story.

“[It] begins with the “confessions” of Hiob von Luzern, a missionary and explorer who, more than 600 years after the letter’s appearance, still hopes to find John. ‘We told each other that he was as strong as a hundred men,’ Hiob writes, ‘that he drank from the Fountain of Youth, that his scepter held as jewels the petrified eyes of St. Thomas.’ Instead, Hiob finds, in a remote village, a tree that grows books, from which he is allowed to pluck three volumes. The first, The Word in the Quince, is Prester John’s own account of his strange adventures, while the next, “The Book of the Fountain, offers the counter-perspective of Hagia, a blemmyae (headless beings whose faces are found on their torsos) who eventually becomes John’s wife. Finally, The Scarlet Nursery is the memoir of Imtithal, a nursemaid who tells her young charges stories of their homeland. As with any fruit, however, the books are quick to spoil, and Hiob must rush from one volume to the next, hoping to translate and transcribe their contents before they completely deteriorate.”

You’ll notice I wrote “science fiction” and not “fantasy” just now; I originally thought this was a clear example of the latter, and I originally wrote the review with that in mind. But, after it had been submitted, Valente set me right in an essay for John Scalzi’s “The Big Idea” series: “It’s a first contact story,” she writes. “The fact is, given the story as it is, Prester John is the only human in the place, and he is king despite having no family in the kingdom and no particular reason to be king. That, friends, is a colonial story… I wanted to tell a story about a man from the West arriving on what is essentially an alien planet, with no one who looks like him, and what he is willing to do to control it, to convert it, to make it like his own land. I wanted to deal with how very much like a natural disaster the arrival of such a person would be, opening up an isolated country to the predations of a burgeoning Europe and a Church hungry for conquest. And I wanted to tell the better part of it all from the point of view of the aliens and monsters who became subsumed into Prester John’s missionary zeal, who make up the complicated folklore we mean when we say: ‘Prester John’s Kingdom.'”

Really, though, you could just flat out call this “literary fiction” and I don’t think very many people would bat an eye, at least not among sincerely thoughtful readers. I made an initial comparison to Umberto Eco’s Baudalino in the opening of the review, and I didn’t make it lightly. It’s that good, perhaps (since it’s been a few years, and my memory of Baudalino is hazy) even better.

8 November 2010 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.