Read This: Richard Powers

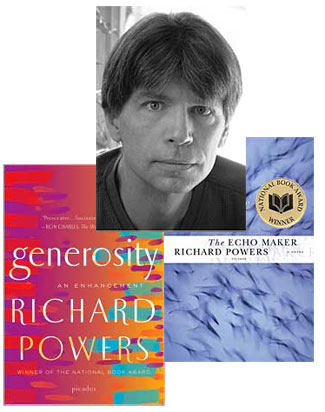

A few weeks ago, I noticed that the Richard Powers novel Generosity had been nominated for the Arthur C. Clarke Award, an annual prize for the best science fiction novel published in the United Kingdom. I was surprised, because although Powers has always had a strong science fictional strain in his work, he’s generally been placed in the literary camp. I hadn’t read Generosity yet, so I picked it up, and wound up writing a short essay for Tor.com about what makes it a science fiction novel. Then, because I was on a roll, I wrote a second post about Richard Powers, this time for Tor’s “Genre in the Mainstream” series, where I focused on an early novel, Prisoner’s Dilemma, and the 2006 National Book Award winner, The Echo Maker.

A few weeks ago, I noticed that the Richard Powers novel Generosity had been nominated for the Arthur C. Clarke Award, an annual prize for the best science fiction novel published in the United Kingdom. I was surprised, because although Powers has always had a strong science fictional strain in his work, he’s generally been placed in the literary camp. I hadn’t read Generosity yet, so I picked it up, and wound up writing a short essay for Tor.com about what makes it a science fiction novel. Then, because I was on a roll, I wrote a second post about Richard Powers, this time for Tor’s “Genre in the Mainstream” series, where I focused on an early novel, Prisoner’s Dilemma, and the 2006 National Book Award winner, The Echo Maker.

In an interview with The Believer, Powers said something I thought really spoke to the science fiction side of his writing:

“We often assume that novels of ideas and novels of character are mutually exclusive. My entire writing life, I’ve wanted to suggest that all novels are to some degree both and that some novels try to erase that artificial boundary in order to show the links between thinking and feeling. We’re all driven by hosts of urges, some chaotic and Dionysian, some formal and Apollonian. The need for knowledge is as passionate as any other human obsession. And the wildest of obsessions has its hidden structure. Our theories about the world are deeply emotional, to us. Voiced idea is character.”

This is something Powers has improved at exponentially over time—Prisoner’s Dilemma has some great ideas, for example, but its characters read like templates rather than people, while the emotional underpinnings of The Echo Maker and Generosity are just as strong as the intellectual underpinnings (although not everyone agrees with me; I can see where William Deresiewicz is coming from in that review, but I don’t agree with him on the later books). I also became intrigued, as I was doing the reading for these articles, how often Powers returns to the theme of a disillusioned writer, someone who begins to mistrust the fundamental nature of his art, grappling with the mysteries of consciousness; Galatea 2.2, Powers’ most explicitly SF novel, falls firmly into this category. Lately, I’ve come to see in Powers’ fiction a sort of parallel to the later work of Phliip K. Dick, especially the VALIS trilogy: thoughtful, and increasingly compelling, meditations on what it means to be human and, in the most recent work especially, how we experience that humanity.

6 May 2011 | read this |

Read This: Charles Dickens (by Michael Slater)

Last week, I had the opportunity to hear acclaimed Dickens biographer Michael Slater give a late morning lecture about “Dickens’ Shakespeare,” as part of the 92nd Street Y’s “Books and Bagels” series (which used to be known as “Biographers and Brunch”). It was a marvelous talk, in which we learned much about Dickens’ utter disregard for his hero’s biography, preferring to focus on the stories themselves, and frequently Slater would illustrate his theme by reading from Dickens—Nicholas Nickleby and Great Expectations, for example—with a flair for voices that rivalled Sloppy in Our Mutual Friend. (I was assured that the 92Y had recorded the audio from Slater’s talk, and I really hope they put at least one of these segments online.)

Last week, I had the opportunity to hear acclaimed Dickens biographer Michael Slater give a late morning lecture about “Dickens’ Shakespeare,” as part of the 92nd Street Y’s “Books and Bagels” series (which used to be known as “Biographers and Brunch”). It was a marvelous talk, in which we learned much about Dickens’ utter disregard for his hero’s biography, preferring to focus on the stories themselves, and frequently Slater would illustrate his theme by reading from Dickens—Nicholas Nickleby and Great Expectations, for example—with a flair for voices that rivalled Sloppy in Our Mutual Friend. (I was assured that the 92Y had recorded the audio from Slater’s talk, and I really hope they put at least one of these segments online.)

During the Q&A period, Slater described how he had first read Oliver Twist when he was ten years old, “and I was absolutely frightened to death. I didn’t find it funny at all; I found it terrifying.” But he didn’t shy away from reading more, all of which he pursued on his own: “Fortunately, I was never taught Dickens. It just never came up in school.” Even at Oxford, when he declared that he wanted to write a thesis on Dickens, they didn’t quite know what to make of him. What was the subject, somebody in the audience asked? “I’m not sure I can remember now,” he admitted. “The composition…? And reception…? of Charles Dickens’ The Chimes… Sounds gripping, doesn’t it?” (It actually did sound fairly interesting; apparently he went through newspapers from the period looking for the stories that Dickens used as source material for the second of his Christmas books.)

I confess that I haven’t had time to do more than dip into Charles Dickens, which we’ve actually had on our bookshelf for some time; but I did take a look as preparation for Slater’s lecture, and what I read was quite excellent: You could tell Slater knew his stuff, but he wasn’t being ostentatious about it, and he was still able to marshall all this information into the form of a compelling story. More years ago than I care to admit just now, I read Peter Ackroyd’s Dickens, and I loved it, but a lot of information has come to light since then—Slater seems to have more than risen to the challenge, and I may just have to plunk this book into my carry-on bag on my next prolonged vacation, when I’ll have the time to properly devote myself to it.

28 April 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.