What I Was Reading All Last Month

You haven’t heard from me much these last few weeks, and for that I apologize. The good news is most of my radio silence was due to working hard, including two speaking gigs in Oxfordshire and Saskatchewan, but mostly the usual assortment of book reviews and other freelance writing. In my capacity as the literary correspondent for USA’s Character Approved blog, I’ve written about Feynman, a biographical “graphic novel” about the Nobel-winning physicist who was one of my inspirational role models after I discovered his memoir, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, as a high school student. I also encouraged folks to check out memoirs by Binyavanga Wainanga (One Day I Will Write About This Place) and Lucette Lagnado (The Arrogant Years, a fantastic biography of David Matthews of his childhood friend (Kicking Ass and Saving Souls), and powerful novels by Amy Waldman (The Submission) and Jesmyn Ward (Salvage the Bones).

I’m really enjoying this gig, because it’s exactly what I want to do—taking a book that deserves a large audience and putting it in front of more people, with the hope that I can encourage even a few people to give it a try. That’s also the impetus behind the “Whatcha Reading?” series I do at inReads.com, except that there I film other authors and their recommendations. Early in September, after writing about her memoir, Yoga Bitch, at the USA blog, I met Suzanne Morrison and got her talking about Colette…

And, because I knew from her own book that she enjoys reading spiritual conversion memoirs, I gave her the copy of Carolyn Weber’s Surprised by Oxford, a story about a Canadian woman who went to Oxford in pursuit of an advanced degree and wound up discovering and embracing Christianity. The conversations felt a bit too well-laid-out in some patches, but overall I thought the way she frames her story gives a compelling dramatic thrust to the struggle to deal with her personal spiritual upheavals in the context of a largely secular and vigorously postmodern academic environment. (And a reminder that sometimes we find allies in the places and at the times we least expect them!)

Oh, and over at Reader’s Entertainment, I had some questions for Lee Goldberg about signing with Amazon.com’s mystery publishing imprint, Thomas & Mercer, to publish the Dead Man series, a series of monthly horror/adventure novels starring a character Goldberg co-created with William Rabkin. They’re essentially “show runners,” making sure the novelists hired to write each installment stay close to the central concepts while otherwise letting their imaginations loose. I’m really curious to see how this project turns out—the rise of electronic publishing has shown us that there’s a fairly healthy market for genre stories that the print publishing sector didn’t necessarily view as sustainable, and as a fan of “men’s adventure” characters like Remo Williams, the Destroyer, or Casca the Eternal Mercenary, I’d love to see some new franchises emerge and flourish.

4 October 2011 | read this |

Read This: Becoming Ray Bradbury

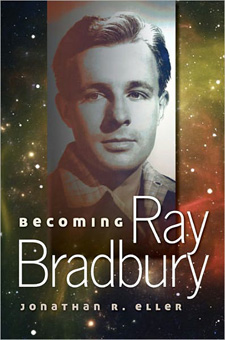

A while back, I did a review for Shelf Awareness of Becoming Ray Bradbury, a critical biography that pays close attention to Bradbury’s formative years, showing how his early love for science fiction and fantasy was tempered on the forge of literary ambition to create a distinctive voice, a steady process of refining his craft that culminates (at least in this particular analysis) with the publication of Fahrenheit 451—perhaps the one science fiction novel any random American under the age of 60 is likely to have read, thanks to generations of junior high and high school English teachers. And yet that very ubiquity can make it easy to forget that Bradbury wasn’t always quite so iconic; Jonathan Eller does an excellent job of recounting Bradbury’s long struggle for acceptance by literary lions, not just as the one science-fiction guy they could stand but as a “real” writer.

A while back, I did a review for Shelf Awareness of Becoming Ray Bradbury, a critical biography that pays close attention to Bradbury’s formative years, showing how his early love for science fiction and fantasy was tempered on the forge of literary ambition to create a distinctive voice, a steady process of refining his craft that culminates (at least in this particular analysis) with the publication of Fahrenheit 451—perhaps the one science fiction novel any random American under the age of 60 is likely to have read, thanks to generations of junior high and high school English teachers. And yet that very ubiquity can make it easy to forget that Bradbury wasn’t always quite so iconic; Jonathan Eller does an excellent job of recounting Bradbury’s long struggle for acceptance by literary lions, not just as the one science-fiction guy they could stand but as a “real” writer.

Fortuitously, Harper Perennial has just put out the paperback edition of A Pleasure to Burn, a collection of several of the stories Eller discusses—stories in which Bradbury first began to grapple with the themes of Fahrenheit 451. There are stories about book burning, and about the resistance that can be offered against it—and the resistance that can be offered against any attempt to stifle our imaginations. But there are also stories about the rise of the type of government that would believe book burning would be an acceptable form of social engineering, where walking along a sidewalk becomes a suspicious activity and contingency plans have been drawn up for the garbage trucks to collect the corpses after a nuclear war. And there are the two novellas, “Long After Midnight” and “The Fireman,” that serve as “trial runs” for the novel, both centered on the fireman Montag and his growing attraction to the forbidden books and the freedom of thought they represent. (Note: “Long After Midnight” is not the story which appeared years later in a short story collection of the same name; essentially, it’s a first draft of “The Fireman.”)

I had a great time with Eller’s biography; he’s extremely rigorous about tracking the details of Bradbury’s literary development without getting bogged down in an academic prose style. So my interest never flagged, and though I knew the rough outcome—I read Fahrenheit 451 in junior high, too—I wanted to hear all the details. And I really want the sequel that Eller ought to write, since he ends the story just as Bradbury is about to head off to Ireland to write a screenplay of Moby DIck for John Huston. That’s a story I want to hear…

27 August 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.