Read This: Zone One & the Literary/Genre Blur

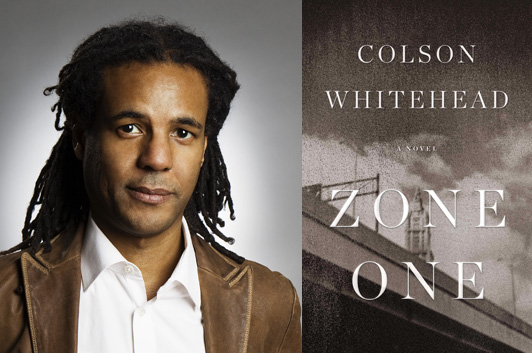

Last month, one of my Character Approved book selections was Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, a novel about a foot soldier in the battle to reclaim lower Manhattan after the zombie apocalypse. It’s a great story, especially if you’re already a fan of Whitehead’s cool, detached voice, which fits this world—where everybody suffers from one form of “post apocalypse stress disorder” or another—perfectly. Like many classic zombie stories, Zone One has its share of satirical social commentary, including some unsettling echoes of Abu Ghraib, but at its core, this is a story of existential isolation… with some kick-ass action sequences.

Much of the critical reaction to Zone One centers around the “fact” that Whitehead is a “literary” author who’s decided to move into genre—which sort of ignores the weirdness of his first novel, The Intuitionist, but Whitehead himself doesn’t care about the distinctions between literary and genre fiction: “They don’t mean anything to me,” he says in an Atlantic interview. “They’re useful for bookstores, obviously. They’re useful for fans. You can figure out what’s coming out in the same style of other books you like. But as a writer they have no use for me in my day-to-day work experience.” Some critics, and critical institutions, care a lot, which is how you wind up with ridiculous, insipid statements like the lead sentence of Glen Duncan’s NYTBR review of Zone One: “A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star.”

At first glance, one wonders why the New York Times would assign a “genre” novel to somebody who is so actively resentful of genre fiction and its fans—even as he makes big money from Knopf off werewolf stories—when they’ve already got a thoughtful critic of horror fiction in Terrence Rafferty. Maybe he just didn’t want to revisit zombies after surveying the topic back in August, or maybe the book review’s editors set out to deliberately provoke the sort of controversy that generates a lot of page views. Your guess is as good as mine. (Meanwhile, Charlie Jane Anders did a fine job of demolishing Duncan’s two-pronged cultural snobbery.)

Using Zone One as a prominent example, Joe Fassler wrote an article for The Atlantic about the increased presence of genre tropes in literary fiction, and I think that article gets at some salient points about how “today’s serious writers” are “yoking the fantasist scenarios and whiz-bang readability of popular novels with the stylistic and tonal complexity we expect to find in literature.” I’d suggest, though, that the “sea change,” to use Fassler’s description, isn’t in what “serious writers” are doing but in what “serious critics” are noticing and/or willing to discuss. We’ve always had writers who’ve combined “genre tropes” and “literary grace” in their fiction; some of them were published as science fiction or fantasy, some as mainstream literary fiction. (The principle holds true for other genres as well.) And this recent wave of high-profile novels with genre elements certainly hasn’t negated the persistence of realism as a literary device… More thoughts in this vein soon.

Read This: In Other Worlds & 11/22/63

Yesterday, I had a review in Shelf Awareness for Readers, talking about In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination, a collection of essays where Margaret Atwood elaborates on her relationship to science fiction—what she thinks it is, and why she wasn’t writing it all those times you thought she was writing it, although she has tried writing it and she likes some of the things other people have done with the genre.

Yesterday, I had a review in Shelf Awareness for Readers, talking about In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination, a collection of essays where Margaret Atwood elaborates on her relationship to science fiction—what she thinks it is, and why she wasn’t writing it all those times you thought she was writing it, although she has tried writing it and she likes some of the things other people have done with the genre.

I found a lot of things to like in In Other Worlds, but I wasn’t completely satisfied, and in a paragraph that was excised from the final, shorter version of the review, I explained why:

“The problem is that this is all rather a hodgepodge: While the opening section does offer a cohesive theory on the literary roots of modern science fiction—including some interesting glimpses at Atwood’s early academic specialization in a tradition she identifies as the “English metaphysical romance”—the middle section basically extracts SF-themed material from the more expansive essay collection Writing With Intent and adds a few reviews that she wrote after that book was published. Readers will learn that science fiction contains ‘all those stories that don’t fit comfortably into the family room of the socially realistic novel or the more formal parlour of historical fiction,” but they’ll only gain scattered impressions of what those stories might be like, not a comprehensive critical history such as you might

find in the late Thomas M. Disch’s (highly opinionated) The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of.”

It’s basically a question of how tightly Atwood ties all her disparate thoughts on science fiction together: None of her thoughts are uninteresting—in fact, they all struck me as sound, although the opening essays are a bit conventional—they just didn’t seem to gel for me. But she’ll give you plenty to think about, so I encourage you to check the book out if you get a chance, anyway.

I had another review in the daily Shelf, taking on Stephen King’s 11/22/63, a nearly 900-page fantasy about a high school English teacher who’s shown a hole in the space-time continuum that leads back to 1958 and is recruited to spend five years in the past, verify that Lee Harvey Oswald wasn’t part of a conspiracy, and then stop him from assassinating John F. Kennedy. As a story, though, that’s practically an abstraction, even to the protagonist, so King gives Jake Epping more substantial personal motivations to go back in time and then stay there—first to right a tragedy that befell one of his adult GED students as a child, then to preserve his relationship with a librarian in a small town outside Dallas. As I wrote, 11/22/63 “reveals the capacity of ordinary people for extraordinary moments of love and courage,” but keep in mind: When Stephen King puts his characters to the test, he tests them hard.

(And, yes, King fans: Not only does the second act take place in Maine in 1958, it takes place in exactly the town you’d want it to, under those circumstances.)

26 October 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.