Read This: The Graphic Canon

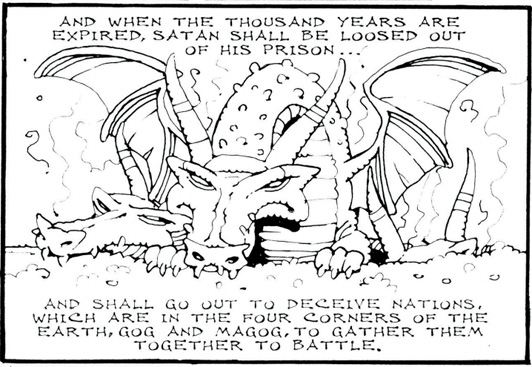

Rick Geary

Seven Stories Press and editor Russ Kick have recently undertaken a multi-volume project called The Graphic Canon, aiming to present a wide sampling of the most recognized titles in world literature, adapted into illustrated formats. The first volume, for example, started with the ancient epic of Gilgamesh and worked its way up to Les Liaisons Dangereuses, while the just-released second volume picks up with Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” and makes it as far as The Portrait of Dorian Gray; a third and final volume scheduled for early 2013 should extend the “canon” to Infinite Jest.

Now, as it happens, I don’t believe in canons—well, obviously, I believe canons exist, as lists of books that certain groups of people deem worth remembering, but I don’t see them as indicators of any intrinsic literary superiority, or even intrinsic literary merit. But a survey of literary history, an extensive checklist of texts that have for whatever reasons had some impact—that could be a very useful thing to have, and so it is in this case. But The Graphic Canon is also a “canon” of late 20th- and early 21st-century illustrators and cartoonists, with contributions from legendary artists like Will Eisner and Robert Crumb, as well as artists who ought to be legendary, like Rick Geary (whose adaptation of The Book of Revelation is sampled above).

It is, however, as mixed a bag as you would expect an anthology with dozens of contributors to be. For every visually fluid work like Noah Patrick Pfarr’s lesbian re-imagining of John Donne’s “The Flea,” there’s an equally static piece like Yien Yip’s version of Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress.” And some of the contributions are not “adaptations” so much as accompanying illustrations, like Molly Crabapple’s (admittedly gorgeous) drawings inspired by Les Liaisons Dangereuses or S. Clay Wilson’s artwork for Grimm and Andersen fairy tales, or Ellen Lindner’s simple, joyful “headshots” accompanying Leigh Hunt’s “Jenny Kissed Me.” But when The Graphic Canon really clicks, as it does with Geary’s Revelation, or Gareth Hinds’s wordless vision of Beowulf, or Megan Kelso’s excerpt from Middlemarch, it shows graphic storytelling techniques at their finest and gives us an alternative entryway into texts whose reputations might sometimes get in the way of our appreciation. (I’m not saying that’s always the case, of course, but there are surely readers for whom, let’s say, the religious significance of Revelation or the sheer size of The Tale of Genji have proved initimidating.)

As part of the buildup to the 2012 Brooklyn Book Festival, Seven Stories is bringing several contributors to the Graphic Canon project together for a free event at The Bell House on September 18. They’ll be joined by my pal Richard Nash of Small Demons, whose catalog of references to people, places, and things in books promises to open up a whole slew of new road maps into literature.

18 September 2012 | read this |

Read This: The Dog Stars

photo: Tory Read

Earlier this summer, I began writing the occasional book review for the Dallas Morning News; my first article was about David Dufty’s How to Build an Android, an account of a university computer science lab’s effort to build a robotic simulation of Philip K. Dick. (And it worked, too, at least until they lost its head…)

For my second Morning News piece, I keep up the science fiction vibe with a look at Peter Heller‘s debut novel, The Dog Stars. Here’s how I described the context of its publication:

In a little over a half century, life after the end of the world has subtly shifted from a topic fit mostly for science fiction, as in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954) or Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Liebowitz (1960), to the stuff of top-shelf literary fiction, most notably Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006).

The Dog Stars positions itself squarely in the latter camp. Although there are scattered references to the superbug that set the novel’s disaster in motion, including a rumor that it might have been a biological weapon, Heller’s focus is firmly fixed on Hig and his shifting emotional state.

Hig is the novel’s 40-year-old narrator, a widow who lives in an abandoned Colorado airport with his aging dog and a sharpshooting survivalist named Bangley. Bangley drives Hig nuts, but he also keeps the two of them alive, and Hig can always get away for a couple days in his small plane. His frustration mounts, though, until one day he sets out after a possible hint of other survivors… As I put it, the book “can feel less like a 21st-century apocalypse and more like a 19th-century frontier narrative… [with] echoes of Grizzly Adams or Jeremiah Johnson,” including some intensely violent scenes. But it’s also a book of “quiet, poetic beauty,” driven not by the plot device of the end of the world but by Hig’s voice. I’d actually set this book aside when I first heard about it, because I didn’t feel up for another literary run at science fictional themes at that moment, but I’m glad that the Morning News encouraged me to take a second look—this is a great story, and I’m interested now in tracking down some of Heller’s nonfiction writing.

29 August 2012 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.