Tyler Knott Gregson: When I Heard Walt Whitman

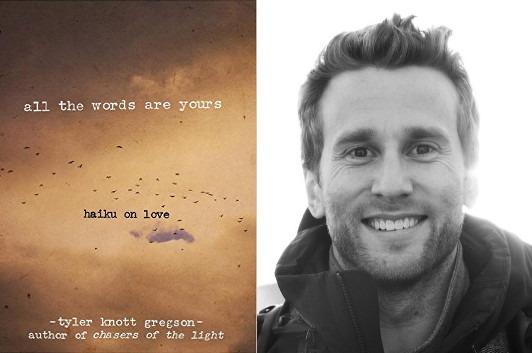

photo via Tyler Knott Gregson

Every day, Tyler Knott Gregson writes a haiku on an old typewriter, and then shares it with fans online. And there’s a lot of them: hundreds of thousands spread out between Tumblr and Instagram alone, with more on other social media platforms. All the Words Are Yours collects some of what he’s shared online along with new work, plus some choice examples of his photography (that’s his day job). “I don’t ever want to be taught how to do something artistic, no matter what it is,” he once told an interviewer, “because I’m always worried that if I’m taught how to do it, I’ll do it like the person that taught me.” But, as you’ll learn in this guest post, inspiration is quite a different matter…

It was one, always one, that pushed me into love. I say pushed because it was forceful, it was unseen, and it took the wind out of me. I had read a few before, poems I was instructed to, guided through, and tested on, but none stuck. None felt whilst reading, how I felt while sitting, staring at blank blackboards, counting every tick of every clock within earshot, waiting for the classes to end. Then it came, as suddenly as the joy rises in his work, as clearly as his observation, and I was pushed into love.

Walt Whitman may seem like a cliché choice to mention as a poet that has helped shape the writer, and more, the man I am today, but like all great clichés, it’s true, and it’s honest. When I first read “When I Heard The Learn’d Astronomer,” something, and maybe it was the first something, made sense, and I for the first time felt like I did, as well. Being taught was something I struggled with, attention span lacks and boredom were things that I wrestled with every day of my school career, and reading this poem served as an introduction not only to Whitman and his entire way of seeing the world, but of being understood by someone, somewhere, even long since gone. Since the first reading, and every time I read it still, it makes me feel like maybe, just maybe the way I see the world isn’t so strange, that maybe it is okay to find miracles in all the mundane and simple things, that maybe walking in complete amazement at all times is a blessing, and not a curse to be corrected and normalized.

18 October 2015 | poets on poets |

Sara Wallace: Smoke in Streams of Light

photo: Rose Ann Franklin

Sara Wallace writes poems with vivid details, immersing you in her scenes, whether it’s a walk through the narrator’s grandparents’ farm in “Take This Old Coat” or the unflinching depiction of an abusive relationship in “You.” But her poetry can’t be reduced to “naturalism” on the one hand or “raw emotion” on the other; it’s the two elements in tandem that make the poems in The Rival stand out. It’s a point she takes up in this guest post, with reference to some of her own favorite poets…

I wanted to start with noir.

A woman’s dress like a tight shadow,

her fingertips dipped in darkness.

Beauty reduced to Glamour and made Suspect.I am endlessly fascinated by Reality and Imagination and my favorite writers comment on and complicate this supposed binary. On one side, we have Reality—the commonplace, the solid, common sense, “salt of the earth” people and the hum-drum comfort of greasy spoons, where we “burst the bubble,” and “come back down to earth,” but where we also see “the cold light” and “hard truths,” where humankind’s greed and brutality are mundane givens. On the other side, we have Imagination—that imaginary get-away with a longed-for yet imminently unattainable Beauty, the “mystic visions and cosmic vibrations” (Allen Ginsberg, “America”) of faith, encounters with inspiring art, where there is charm, elegance, and wonder but where there is also affectation, ostentation, pride, “spells and incantation” (Keats, “To…”), and the constant danger of aesthetic failure (“I am going to dream up a tiger,” Borges writes in “Dreamtigers.” “Utter incompetence! A tiger appears, sure enough, but an enfeebled tiger…” )

Indeed, each side of the binary actually has multiple binaries within it, like the fractals studied in chaos theory. The most interesting contemporary poets play with this “hall of mirrors” effect. For example, Jack Gilbert’s poem, “Alyosha,” opens with a quasi-Gauguinian moment, with the narrator seemingly fetishizing locals: “the sound of women hidden / among the lemon trees.” The work as a whole, however, is hardly a simple celebration of primitivism (which, after all, exists in the imagination of the beholder). Gilbert’s disillusioned narrator knows that the reality of Beauty’s life is often terrible even as he covets her: “He is not innocent. / He knows the shepherdess will be given / to the awful man who lives at the farm /closest to him….”

7 July 2015 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.