Keith Douglas, “Syria”

These grasses, ancient enemies

waiting at the edge of towns

conceal a movement of live stones,

the lizards with hoded eyes

of hostile miraculous age.It is now snow on the green space

of hilltops, only towns of white

whose trees are populous with fruit

and girls whose velvet beauty is

handed down to them, gentle ornaments.Here I am a stranger clothed

in the separative glass cloak

of strangeness. The dark eyes, the bright-mouthed

smiles, glance on the glass and break

falling like fine strange insects.But from the grass, the incurable lizard,

the dart of hatred for all strangers finds

in this armour, proof only against friends,

breach after breach and like the gnat is busy

wounding the skin, leaving poison there.

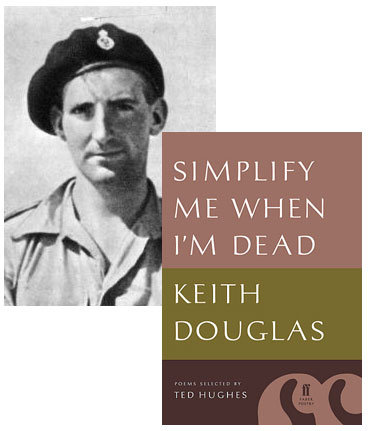

People rightly remember the great British poets of the First World War, such as Wilfred Owen, but here in the States, at least, we have not heard nearly as much about Keith Douglas, who served with the Army in North Africa during the early part of the Second World War and then took part in the landing at Normandy—killed by a mortar attack three days later, at the age of 24. Simplify Me When I Am Dead, first published in 1964, is a powerful distillation (with poems selected by Ted Hughes) of his power. “Although they’re all set against the backdrop of the Second World War, they don’t deal much in politics and history, taking the enormity of their period as a given,” observed Ali Shaw. “Instead they focus on what it’s like to be alive in such times.”

Other poems include “Vergissmeinnicht (Forget-Me-Not)” and “How to Kill.” And, too, here’s an odd little film, a computer simulacrum, based on a photograph of Douglas, reading the poem that gives this collection its name:

26 May 2010 | poetry |

Paul Farley, “Johnny Thunders Said”

You can’t put your arms around a memory.

The skin you scuffed climbing the black railings

of school, the fingertips that learned to grip

the pen, the lips that took that first kiss

are gone, my friend. Nothing has stayed the same.

The brain? A stockpot full of fats and proteins

topped up over a fire sotked and tended

a few decades. Only the bones endure,

stilt-walking trhough a warm blizzard of flesh,

making sure the whole thing hangs together,

our lifetimes clinging on as snow will lag

bare branches, magnifying them mindlessly.

Dear heart, you’ve put a brave face on it, but know

exactly where the hugs and handshakes go.

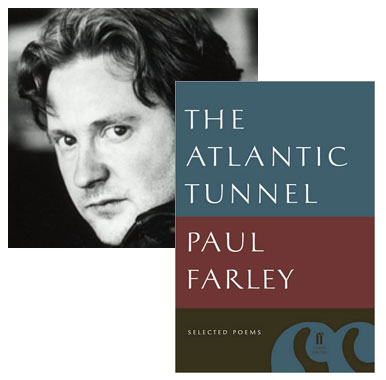

The Atlantic Tunnel is a selection of poems from four previous collections by Paul Farley; the poem above is immediately preceded by “Tramp in Flames,” the title poem of a volume shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize…

Other Farley poems include “Monopoly” (published in The Poem) and “Cyan” (Granta), the latter of which leads off the section of new poems in The Atlantic Tunnel. New Yorkers will have a chance to hear more from Farley Tuesday night; he’s reading at 192 Books with Paul Muldoon.

Embedding has been disabled for the video of Farley reciting “Liverpool Vanishes for a Billionth of a Second,” but I encourage you to go have a look.

16 May 2010 | poetry |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.