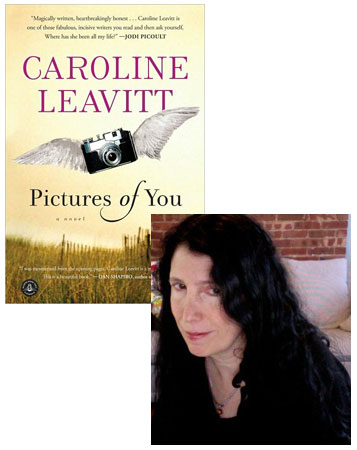

Caroline Leavitt: Literary Can Be Commercial & Vice Versa

I got an email late last year from Leora Skolkin-Smith reminding me that our mutual friend, Caroline Leavitt, had a new novel coming out at the start of 2011. Since then, Pictures of You has been getting a lot of attention, and a reputation as the year’s first breakout “upmarket commercial” novel. (“Upmarket commercial” in this context is marketing language for “a very compelling story told in very polished prose,” and at 150 pages in, I can confirm that characterization.) Caroline and Leora have known each other since they began working together on adapting Leora’s novel, Edges, into a screenplay (now in preproduction with Triboro Films). “We soon began sharing the travails and triumphs of the writing life with our novels,” Leora says, “and then began sharing our personal lives, as well, until now we’re pretty inseparable.” So with Pictures of You arriving in stores, it seemed like a natural fit for Leora to ask Caroline some questions about the novel.

Your blurbs are a truly unusual mix of writers, running the gamut from Robert Olen Butler to Jodi Picoult. Some are intensely “literary”, even “experimental”, and others, talented genre writers. You have a democratic notion of literature and story-telling and you don’t wage an battle against either camp—the “literary” or the “commercial”, a battle that seems to be always flaring up in our writing world far too often (for me anyway). Can you talk a little about your understanding of genre, of fiction and story-telling? And how you see this battle as it wreaks havoc on our collective literary universe?

I hate the notion of genre, because I think it stonewalls the reading experience. Why can’t a literary novel also be a commercial page-turner? Why can’t a commercial romance also be literary? Why do we have to pigeonhole books and writers as if readers aren’t smart enough to discover what a book is offering them just by reading it? I’m hoping the lines between literary and commercial are going to blur more and more. (Case in point: Look at Justin Cronin who wrote a literary and highly commercial vampire novel!) I deliberately wanted to span the gamut of writers for blurbs for Pictures of You—male, female, literary and commercial—simply wanted to underscore that hopefully, a wonderful read is a wonderful read and we really don’t need to always be making value judgments about a book before we’ve even read past the first chapter.

26 January 2011 | interviews |

Paul Murray: Filling in the School Novel’s Margins

If only the café down the street from Paul Murray’s hotel had donuts—our interview could have had that extra little touch of Skippy Dies resonance. No such luck, but once I’ve brought a latte and a tea back to our table, we’re able to plunge into a wonderful conversation. I began by observing that if you read his first novel, An Evening of Long Goodbyes, as an answer to the question “How do you pull off Wodehouse comedy in the 21st century?”, Skippy Dies could be seen as an answer to, “OK, then, how do you do the boarding school novel in the 21st century?” But of course Murray isn’t systematically working his way through the sub-genres of the 20th-century British novel. “I just found the environment of the school very enjoyable to write about,” he explained. “However many characters you want… the setting brings everything together.”

The novel had its origins in a short story about a biology teacher and one of his students, who had turned in a paper about “sea enemies;” when that story passed the 60-page mark, however, he tried to figure out how to scale it back. Then his brother suggested that maybe the answer was to build it out even further, into a novel, and Murray remembered a fragment of a story he’d written years earlier, about two schoolboys sitting in a diner having a donut-eating contest when one of them dies, and not from the expected causes…

“But the conventions of [the school novel] are so strong that you have an architecture given to you,” he reflected. “Most readers are so familiar with the scenario that you can experiment with the edges and take the story to different places. And if you have the grounding and a foundation that’s familiar to you, it’s easier to know what to leave out and get to the core of the story quicker.” So the novel’s Seabrook College is, he admitted, “pretty identical” to his own school (“although I wasn’t boarding, thank God”), enough that former classmates would be able to recognize the layout and the buildings. “But the teachers I invented… I never feel right about using characters from real life; they never quite fit the bill.”

10 December 2010 | interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.