Haikasoru: Translating Genre from Japan

Earlier this week, The World SF Blog paid tribute to Haikasoru, an imprint of VIZ Media focusing on English-language translations of Japanese science fiction and fantasy. Haikasoru’s editorial director, Nick Mamatas, contributed a post on some distinctive features of Japanese SF, both cultural and literary—especially the fact that, although “Japanese SF authors grew up reading US and UK SF and have fully embraced the idiom,” in these books “the future is Japanese,” and it can be very edifying for Western readers to be exposed to more non-Anglo, non-American visions of the future.

Earlier this week, The World SF Blog paid tribute to Haikasoru, an imprint of VIZ Media focusing on English-language translations of Japanese science fiction and fantasy. Haikasoru’s editorial director, Nick Mamatas, contributed a post on some distinctive features of Japanese SF, both cultural and literary—especially the fact that, although “Japanese SF authors grew up reading US and UK SF and have fully embraced the idiom,” in these books “the future is Japanese,” and it can be very edifying for Western readers to be exposed to more non-Anglo, non-American visions of the future.

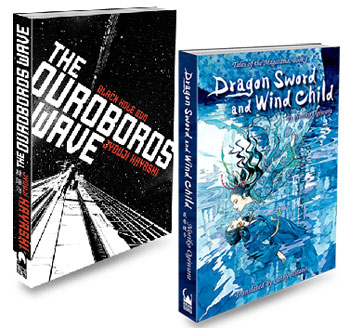

His post reminded me that I’d actually gotten in touch with the folks at Haikasoru a while back, with the idea of soliciting some guest essays from their translators for the recurring series here at Beatrice, and that Mamatas had kindly put together a bit of Q&A where he approached Jim Hubbert and Cathy Hirano and asked them about their work on novels like Jyouji Hayashi’s The Ouroboros Wave and Noriko Ogiwara’s Dragon Sword and Wind Child. I’ve been meaning to post this for a while, and I’m glad I finally pulled myself together and got it online, because there’s some really wonderful insights into translation in their answers to Mamatas’ questions. “The Japanese science fiction and fantasy we publish is meant to compete against the best English-language books on the shelves,” he wrote in his introduction to this piece. “For that I needed translators who had the instincts of novelists, and those are few and far between.” Based on these answers, and what I’ve read of the books, he’s found at least two winners.

What’s it like, being North Americans in Japan and working as translators?

Jim Hubbert: This is a bit hard to answer. Since I’ve spent most of my adult life in Tokyo, I’m not sure what it would be like to be a translator in North America! Japanese has been a central interest of mine since the mid-70s, and I can’t imagine being away from the environment where it’s spoken. I suppose I could be based somewhere else and translate, but without having the language coming at me every day, I’d worry that my instincts for meaning and nuance would suffer a bit. Japanese is a radically different vehicle of expression from my native English, and it still gets the drop on me regularly, which is part of the fascination.

Since I’m based in Japan, keeping my own idiolect current and evolving is something I try to work at. Through entertainment and the Internet I have no shortage of access to the English language—better access than I’d have to Japanese, were I outside of Japan—but I try to keep myself exposed to different voices. I don’t have a huge fiction library, but if I like something, I’ll go back to it every few years. Some nonfiction is amazing from a language standpoint, like Shelby Foote’s Civil War trilogy, which was my mental tuning fork for rendering some of the violence in The Lord of the Sands of Time.

I think of the time I spend reading fiction as another form of language study. Authors have their own distinct idiolects. Without diverse exposure to what can be done with English, I’d have a harder time finding the right tone when translating fiction.

25 March 2011 | in translation |

Giles Murray on Gush: “Watery, But Certainly Not Grave”

Gush is, as far as I know, the first time that English-language readers have been able to read the fiction of the Japanese poet and social activist Yo Hemmi—thanks to the translation work of Giles Murray. I had a look at the title novella earlier this week, and as Murray discusses in this essay explaining what drew him to the story, it’s a very unusual story, narrated by an insurance salesman who spots a woman shoplifting some imported cheese from a Tokyo supermarket. As she’s leaving, he notices a puddle of water on the floor; when they meet again soon after, she explains that the water builds up inside her until “I know I’m doing something bad, something I shouldn’t, [and] that’s when it comes out.” Of course, this “urge to spout water,” which she views as “a horrible, weird disease,” is basically female ejaculation… but, as our protagonist discovers when he embarks on an affair with her, for this woman it takes place on an epic scale. And, he soon realizes, the source of her deepest shame is also the source of his greatest pleasure. In the wrong hands, this could be crude and farcical, but Hemmi (and Murray) turn it into a melancholic story of the waning strength of impulsive love. (And there are still two other Hemmi stories for me to read after this! I’m looking forward to that.)

Gush is, as far as I know, the first time that English-language readers have been able to read the fiction of the Japanese poet and social activist Yo Hemmi—thanks to the translation work of Giles Murray. I had a look at the title novella earlier this week, and as Murray discusses in this essay explaining what drew him to the story, it’s a very unusual story, narrated by an insurance salesman who spots a woman shoplifting some imported cheese from a Tokyo supermarket. As she’s leaving, he notices a puddle of water on the floor; when they meet again soon after, she explains that the water builds up inside her until “I know I’m doing something bad, something I shouldn’t, [and] that’s when it comes out.” Of course, this “urge to spout water,” which she views as “a horrible, weird disease,” is basically female ejaculation… but, as our protagonist discovers when he embarks on an affair with her, for this woman it takes place on an epic scale. And, he soon realizes, the source of her deepest shame is also the source of his greatest pleasure. In the wrong hands, this could be crude and farcical, but Hemmi (and Murray) turn it into a melancholic story of the waning strength of impulsive love. (And there are still two other Hemmi stories for me to read after this! I’m looking forward to that.)

Alex Kerr, the author of two books on the arts, economy and society of Japan, believes that traditional Japanese culture was defined by the tension between man-made order and the disorder of nature. Stone gardens are one example he gives: Inside the garden, all is cold, sterile, gray and orderly; but immediately outside looms a mountainside heaving with great shaggy cedars, red-leafed maples and gaudy pink camellias. The artful austerity of the garden would be nothing without the wild fecundity of the natural world to set it off. Present-day Japan has erred too far on the side of sterility, artifice and order, argues Kerr, a loss of balance that has been detrimental both to the arts, and to society at large.

The existence of a handful of artists still able to channel Japan’s old earthy and instinctual side gives Kerr grounds for hope. One of these was Shohei Imamura, the movie director best known for The Eel, the 1997 Cannes Film Festival Palme d’Or winner. Prior to his death in 2006, the last full-length feature Imamura made was an adaptation of “Warm Water Under a Red Bridge,” a 1992 novella by Yo Hemmi. This novella has finally been translated into English (in a collection with two other short stories) under the title “Gush.”

11 February 2011 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.