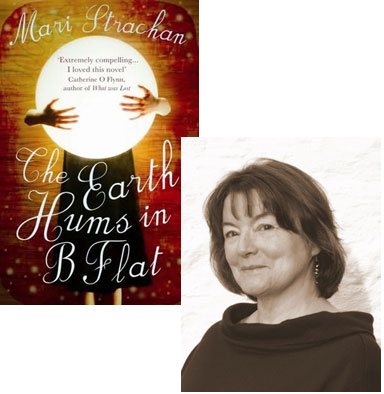

Mari Strachan: A Welsh Novel in English

In a few months, Canongate will be publishing The Earth Hums in B-Flat, the debut novel from Mari Strachan, in the United States, but it’s been out for a while in the United Kingdom—in fact, it’s this week’s selection on BBC Radio 4’s “Book at Bedtime. I’ve been reading a copy of the British edition, and I’m enjoying the story, which Strachan describes as “written in English [but] told in Welsh,” so I encourage American readers to keep an eye out for it. And about that English/Welsh thing? Well, Strachan had an explanation for that, which I’m glad to be able to share with you.

My first language is Welsh, and I learnt English when I started school. At the time when I grew up, Welsh was the language of our hearth and our identity but English was the language of our education, at least at secondary and university levels. So, I speak Welsh to my family—my mother and aunt, my sister, my children and my grandchildren—and I use it in everyday life in shops, cafes, with friends and neighbours and so forth; but because there is a great gap between spoken and written Welsh, I lack the confidence and the practice to use it as a vehicle for my literary efforts.

There’s also the question of who I’m writing the book for. I’m not conscious of writing for any particular audience when I’m working, but I am conscious that I have a desire to explain Wales and the Welsh identity to people who are unaware of them, both within the British Isles and without. The book’s narrator is growing up in a Welsh speaking community where she would not naturally speak English. To make the point that she’s talking to the reader in Welsh I occasionally have someone say something ‘in English’. I had to consider very carefully how to write the Welsh in English, and decided that I would avoid ‘Welshisms’ but use proper names as they would be in Welsh.

I have been surprised by the number of people who have told me they can hear a Welsh ‘lilt’ in the writing. I’m not sure if that is because they expect to hear it, or whether somehow the rhythms and sounds of my first language colour the writing of my second. It’s interesting that in the British Isles only one reviewer, so far, has recognised what I’m attempting to do—an Irish reviewer, whose history has also been shaped by the influence of English governance and its language.

30 March 2009 | guest authors |

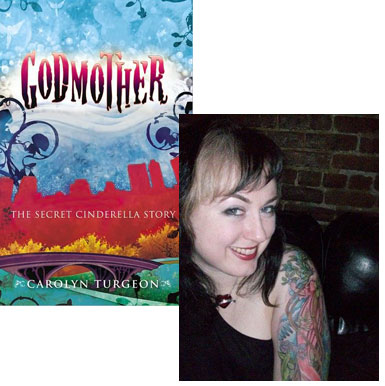

Carolyn Turgeon: What Lies Beneath Cinderella

It’s been nearly two-and-a-half years since my friend Carolyn Turgeon wrote her first guest essay for Beatrice; the publication of her second novel, Godmother, is a perfect opportunity to hear from her again. (She’ll be reading from the novel at the Tribeca Barnes & Noble tonight at 7 p.m., if any of you reading this happen to be in New York City.) She offered to explain how she chose a familiar fairy tale as the basis for her story, and how she began diverging from the well-known story almost immediately…

When I started writing Godmother: The Secret Cinderella Story, I really just wanted to tell the Cinderella story straight-up. With lots of lush, shimmery language and images, lots of rich feeling, all kinds of twists and turns and secret little crevices of the story being revealed. I liked the idea of working with the Cinderella story, because: 1) it was already written, thus halving my work (I thought), and 2) it is just about the prettiest story in the world. Glass slippers and pumpkins and ball gowns and palaces!

And I’m not going to lie: the Cinderella that wormed its way into my deepest heart at a shockingly young age is the Disney one. No stepsisters cutting their heels off to fit into the shoes, no horrific comeuppances… and one puffy cheeked little fairy godmother flitting around to make all Cinderella’s dreams come true.

I also knew, right away, that any retelling of the Cinderella story I’d do would have to be sad. It’s a classic tale of longing: a young girl, abused, betrayed, lost, mistreated, her parents dead, stuck in the house of a woman who hates her, of her stepsisters who hate her, being forced to dress in rags and clean day and night, with nothing to do but imagine every single thing she’s lost or will never have. Her dead parents, her former happiness. The prince, the ball. Becoming someone new.

I have an enormous appreciation of longing. I’ve loved Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave since I was a teenager. I studied medieval Italian poetry in graduate school. I read about theologians and saints. I love quotes like this, from Nick Cave’s The Secret Life of the Love Song:

“We all experience within us what the Portuguese call Saudade, which translates as an inexplicable longing, an unnamed and enigmatic yearning of the soul and it is this feeling that lives in the realms of the imagination and inspiration and is the breeding ground for the sad song, for the Love Song. The Love Song is the light of God, deep down, blasting up through our wounds.”

So here is Cinderella, suffering, full of desire and Saudade. And the ball: it’s a real thing and also the object of every unnamed, inexplicable desire. Isn’t it? How is this poor, dirt-streaked girl going to get to the spectacular, otherworldly ball, anyway? How is she going to be transformed? It’s not the prince who saves Cinderella, after all. The prince just gets hot and bothered over a gorgeous girl in see-through shoes. It’s the fairy godmother who sees past the dirt, the pain and the heartbreak, to all the beauty hidden there.

26 March 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.