Linda Gordon’s Sideways Entry into Dorothea Lange’s Biography

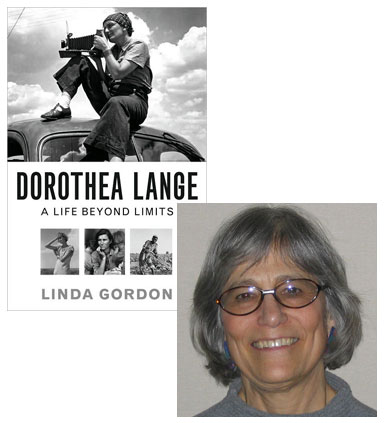

If you read this weekend’s NY Times Book Review, you might have seen where Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits was hailed as “an absorbing, exhaustively researched and highly political biography of a transformative figure in the rise of modern photojournalism.” The book had first crossed my desk a few weeks ago, and when it arrived I had been curious about what had attracted NYU history professor Linda Gordon to Lange as a subject. The answer, which I’m able to share with you now, was surprising—and proof (if any were needed) that a writer should always strive to keep herself open to possibility.

If I were a religious person I might conclude that I was commanded by some greater power to write about Dorothea Lange. One day, around 2001, I got a phone call from a friend in California asking if I’d like to write Lange’s biography. It seemed that a biographer, Henry Mayer, had been planning to write about Lange but died suddenly of a heart attack; friends of his had thought the materials he had collected should be passed on to someone who could use them—and they thought of me.

At first I said no, I’m not a biographer and I don’t know photography. I thought maybe I could help find the right person to take up the project, though, so I began to read a bit about Lange. Soon, coincidences piled up. I had been planning in my next project to write about the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s heroic response to the great depression of the 1930s, and it was the New Deal that gave birth to Lange as a documentary photographer. I had been planning to write about the west—I’m from Portland, Oregon—and discovered that Lange was a westerner and that much of her photography covered the western states, including my own. Another striking piece of serendipity: Her second husband was a scholar whose work I had pored over for my previous book (The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction), never dreaming that he was married to a major artist.

25 October 2009 | guest authors |

Hallie Rubenhold Rediscovers the Worsley Affair

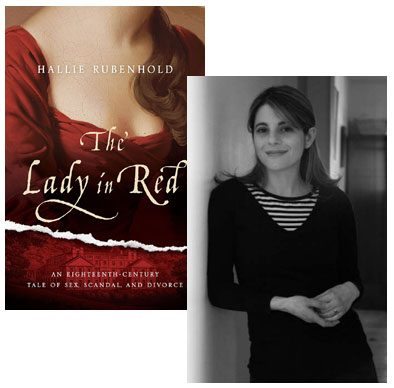

Beatrice is perhaps best known for its focus on fiction; however, my taste in romance novels is influenced in no small degree by an interest in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century British history, so biographies of figures from that period will almost certainly catch my eye—such was the case with Hallie Rubenhold‘s The Lady in Red, which UK readers may readily recognize as Lady Worsley’s Whim. But how did Rubenhold hit upon one of the most notorious sex scandals of the 1780s as her subject? It began, she explains, with a painting…

Call it perverse, but as a historian, I’ve never been interested in telling the epic stories. Yes, I find the big ‘set pieces’; the battles and incidents of court intrigue fascinating. I’m enthralled by monarchs and presidents, wars and turning points, but I’m also strongly of the belief that true history lies in the details. It’s the bits that have been left out of the history books that are crying out to be told. It’s the voices that have been silenced or never heard before which require attention. My gut instinct has always been to mine the archives and dig out the rare gems, which is how I came across the story of Sir Richard and Lady Worsley.

At first I found it amazing that no one had written a book about them; Lady Worsley’s portrait, painted by Joshua Reynolds (c. 1780), is perhaps one of his most striking and bold works. The full-length painting (which now hangs at Harewood House, a stately home in the north of England) features its subject adorned in a blazing red riding habit, her hand tightly gripping a riding crop. Needless to say, her defiant and unconventional stance raised as much comment in the eighteenth century as it still does today.

It seemed odd to me that although so many eyes had examined this image, no one had been compelled to discover the story behind it. In fact, very little at all was known about the Worsleys, and what I did find only piqued my curiosity further. According to the portrait’s catalogue entry, Lady Worsley, her husband, and her lover, Captain George Bisset had been embroiled in one of the greatest sex scandals of the eighteenth century.

24 August 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.