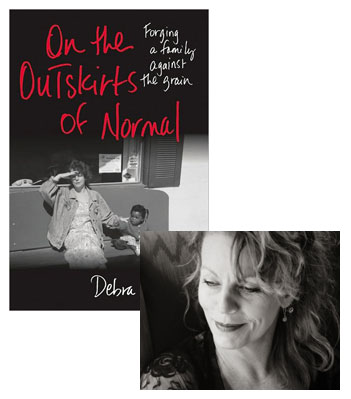

Debra Monroe: Choosing Real Life over Easy Myths

When SMU decided to suspend operations of its university press earlier this year, I tried to put a spotlight on some of the remarkable work that press had done publishing short stories, but that’s not all they do. Debra Monroe‘s memoir, On the Outskirts of Normal, is that rare university press title that makes a big splash in the mainstream book reviewing media, including a recommendation from Oprah magazine. Monroe’s voice is a storytelling natural, conveying her experiences not in the order in which they happened but in a way that makes the most emotional sense. But it almost didn’t turn out that way.

At one point, Monroe took an agent’s suggestion and hired a freelance editor to impose a tighter chronological order on the story of a single white woman adopting a black child. “I would never have agreed at any other time in my life, because I don’t spend money that way,” she told me, but an editor at a large publisher had committed to taking another look at the manuscript if it were revised into a slightly more conventional form. “At the time, I was selling my house, and decisions amounting to a few thousands dollars were going on daily… Well, I did it, but pulled out when it was getting too expensive. (Plus, the freelance editor had started in with the New York-centric conversations about toothless racists in the Texas countryside and the ‘age of Obama’ crap.)” The problem was that the new, linear narrative was, in Monroe’s own estimation, discursive and rambling. “The central conflict was lost because the central conflict had been not-understanding-my-fears (life as chaos) vs understanding-my-fears (life as a story),” she recalled. “Telling the story as the search for meaning required some chronological manipulation.” The agent who’d recommended the freelance editor in the first place declared the results boring, then suggested Monroe juice up the story by emphasizing the racial elements.

So Monroe walked, and when she showed her original manuscript to Kathryn Lang at SMU, “she kept the organization as it was, with the central conflict between life-as-a-series-of-accidents and life-as-a-tale-that-means-something. We worked a bit on more ‘glue’ for the structure, but stayed true to it.” As Monroe explains in this essay, her memoir isn’t a story about transracial adoption, but one in which that experience shapes a much broader transformation.

Fact: My daughter is black, and I’m white. I adopted her when Angelina Jolie was a fashion model, not a movie star or UN ambassador or adoptive mother. The Multiethnic Placement Act had just passed, and ours was the first transracial adoption my agency handled. I was a novelist. I used the advance on my third book to pay my adoption fees. Then I started writing nonfiction. I’d endured a crisis or two. I wanted to revisit these years—certain moments incandescent, others blurry and obscured—and find a plot, not invent one. Love. Death. Illness. Ordinary trouble. I write books because of the way I read: I want my books to get some reader through one of those dark nights of self-doubt.

I’d published previous books with both small and large presses. In my experience, small presses provide the most intelligent, passionate editing on the planet, but they have few resources for distribution and publicity. Because large presses have more of the latter, they deliver more readers. So I hoped to sell my book to a large press. People really liked the concept: white woman, black child, small Texas town. I felt racial and geographical assumptions falling into place. During long phone calls and protracted emails, the phrase “the age of Obama” came up. So did market exigencies.

But the advice that stopped me in my tracks was to emphasize race more; an agent described inconceivably huge advances if I would. But how? We encountered worse problems with racism and. . . I taught the town a lesson? I overcame racism? The needle on my moral compass went haywire.

21 July 2010 | guest authors |

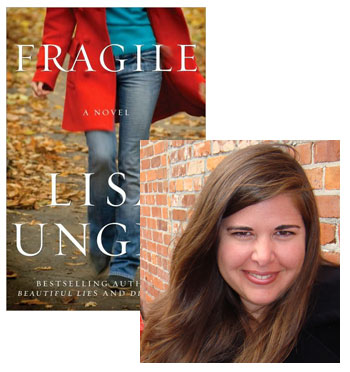

Lisa Unger & The Heart of the Story

If you’ve been reading Beatrice long enough, you’ve probably figured out that I don’t care too much about genre labels—as far as fiction is concerned, it’s all just one big stack of stories to me, and what matters is: Is it told well? Lisa Unger’s essay about the origins of her new novel, Fragile, speaks to the arbitrary barriers publishers, bookstores, and critics use to keep some books separate from others, but it’s also about how stories can come to writers who aren’t quite ready to tell them, and what happens when those stories won’t go away.

Once upon a time, an editor I had respected and from whom I had learned quite a bit suggested, as she turned down my novel, that I make some decisions about myself. In fact, what she said precisely was, “Lisa, you have to decide what you are. Are you a literary writer? Or are you a mystery writer?”

I didn’t really consider myself either one of those things; I had never endeavored to define myself as a writer of anything but story. When I began my first novel at the age of nineteen, I didn’t sit down to write a mystery novel or a literary novel. I was just writing what I wanted to write… and that was a story about a troubled woman who had chosen a dark profession to try to order the chaos she perceived in her life and in the world. There was a psychic healer, a former FBI agent, and a high body count. So, yes, I supposed when the book was done, it was in fact a mystery—or a maybe a thriller. Possibly, it was crime fiction. The point is: When my fingers were at the keyboard, the question of what space it would occupy on the bookshelf simply never occurred.

It took me ten years to finish and finally publish that novel, and then I published three more “mystery novels” under my maiden name Lisa Miscione. They were small books, based on an idea that I had when I was really too young to be writing books. Though they will always occupy a special place in my heart, I consider them the place where I cut my teeth, honed my craft and became a better writer.

Now, with eight novels on the shelves, one about to be published, and my tenth nearing completion, I still don’t give too much thought to who I am as a writer, what kind of books I’m writing. I am published in a place where people support the evolution of my fiction. At Shaye Areheart Books, I have never been asked to define myself or to change how and what I write. So when my wonderful editor said how different she thought Fragile was, her statement wasn’t followed (thankfully) by “We can’t publish this.” Still, the idea that the novel was not like what came before it caught me off guard. Wasn’t it? It didn’t feel different when I was writing it. Though I did have a sense that it was heftier in some way, harder to manage.

19 July 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.