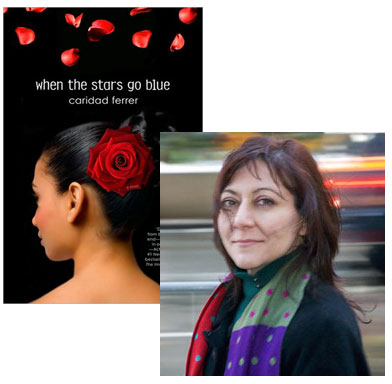

Caridad Ferrer’s All-Too-Timely Ballet Novel

Earlier this week, a friend of mine on Twitter mentioned a link to an essay at BlogHer.com about how the ballet critic for the New York Times had been making cracks about ballerinas’ body shapes, and the incredibly lame defense he’d offered for doing so after the initial protests: “If you want to make your appearance irrelevant to criticism,” he wrote, “do not choose ballet as a career.” (Right: It’s not about the moves, it’s about whether you look right making them. Sure.)

As the discussion about the article continued, my friend Caridad Ferrer observed that this controversy provided much of the emotional fuel for her new novel, When the Stars Go Blue, about a recent high school graduate and aspiring ballerina who takes a detour through the drum and bugle corps when an opportunity to play Carmen arises. I figured Caridad had a lot more to say about this than you could fit into a 140-character tweet, so I invited her to write an essay for Beatrice…

Alistair Macaulay is an unmitigated jackass.

Okay, had to state that right off the bat. Just get it out there. Sadly, however, he’s an unmitigated jackass to whom I owe something of a debt and believe me when I say, I wish that wasn’t the case.

Right now, you’re probably wondering “Who?” and “Why?”

Alistair Macaulay happens to be the ballet critic for The New York Times. As to why I owe him a debt—well, it’s because his recent critique of the New York City Ballet’s holiday production of The Nutcracker (as choreographed by George Balanchine) provided a timely reinforcement of a plotline from When the Stars Go Blue. My lead character, Soledad Reyes, is a dancer. About to graduate from an elite high school for the arts in Miami, she has aspirations to become a professional—her focus primarily on ballet—even though she knows the odds are stacked against her, even more so than they would be for anyone desiring a career in such a demanding profession. Because, you see, Soledad is what one might consider a non-traditionally sized ballerina.

17 December 2010 | guest authors |

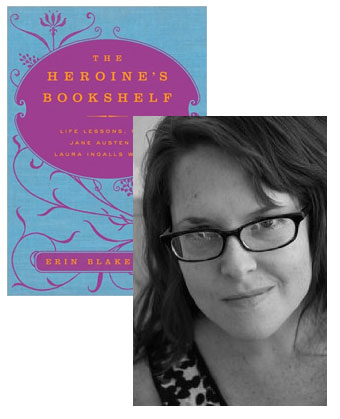

Erin Blakemore: Standing Down Literary Intimidation

The “Intimidation” that Erin Blakemore writes about in the essay you’re about to read is of a kind with the Resistance Steven Pressfield discusses in The War of Art, one of my all-time favorite books about creativity, and we’re fortunate that Blakemore prevailed and completed The Heroine’s Bookshelf, a delightful guide to what the heroines of some of the great novels by women writers, and those writers themselves—from Pride and Prejudice to The Color Purple, or from Laura Ingalls Wilder to Colette—can teach us about life.

By the way, New Yorkers: If you’re free Tuesday evening (October 26), you might join Blakemore at Bookbook (266 Bleecker Street) at 6:15 p.m., where she’ll kick off a women’s literary walking tour of Greenwich Village—you’ll see the house where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women as well as the homes of authors like Edith Wharton, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Alice Walker—followed by a discussion back at the bookshop. If you do decide to go, and you’re on Facebook, please RSVP; it’s always helpful to have an idea of how many people might show up!

The longish pause that separated my book deal from my book writing really shouldn’t have happened. I was on a tight deadline, inundated with commitments to my day job, and riding high on the wave of a debut book contract. What was my problem, again?

I blamed. Myself, of course. Couldn’t I have picked a less intimidating subject than the great heroines and authors of literatures for my first published book? Sadly, I was the kid at school whose arm went numb with handraising and who always chose the 3,000-page tome when the 30-page children’s book would do. Add overachievement to hubris and BANG, there I was, popcorn seeds all over my pajama top, wringing my hands over the blinking cursor at 4 a.m.

Weak.

25 October 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.