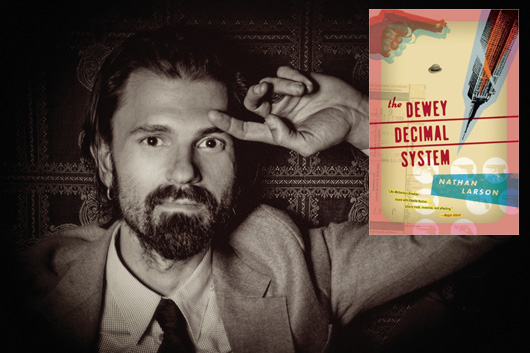

Nathan Larson: Diving into Dewey Decimal’s World

Akashic Books

I’d made tentative plans earlier this summer to interview Nathan Larson for one of the Beatrice ebooks, and when we couldn’t quite get our schedules to sync up, I knew I still wanted to get him talking about his first two novels, The Dewey Decimal System and The Nervous System—the opening salvos in a “dystopian noir” series set in a post-disaster New York City, where an amnesiac veteran who’s taken it upon himself to safeguard the main Public Library building gets dragged into a bunch of other messes and, as your noir heroes do, pushes at them over and over until he provokes traumatic outbursts. If you’re not from the city, you’ll have to take my word for it, but Larson gets the street-level details meticulously right; even in post-disaster condition, you could navigate the city by his descriptions, no problem. (The scope of what happened to the city—and the world—is unclear, though there are hints throughout the two books of a string of coordinated incidents; there are also several hints about Dewey’s pre-disaster past, though those clues haven’t quite gelled together yet.)

Here, then, is Larson’s take on his shift to fiction writing after (or, rather, in addition to) a productive music career that includes playing guitar for Shudder to Think back in the ’90s and subsequently composing film scores.

Y’all, I am brand spanking new to this writing game, and don’t pretend to have any answers with respect to how it’s done. Like any creative endeavor, it seems to have something of the esoteric about it, and when it flows it feels very much like one has tapped into some sort of cosmic cloud of information for which the author serves as conduit. There’s nothing new about this description; greater minds than mine have waxed upon the subject. It’s exactly the sensation I’ve experienced working as a musician, so I’m not a stranger to this thing—but I find it fascinating to observe this phenomenon at work regardless of the medium.

Of course this kind of hippy shit occurs about 5 percent of the time, and the other 95 percent is pure slog and persistence. It’s work, it’s a jobby-job. And this too is exactly like making music. If I’ve learned anything about writing, whether I’m speaking about prose or film scores or songs or whatever, it’s that you have to sit down and do it, and you have to finish it, and it will suck, and then you go back and make it not suck, to the degree that you are willing and able. Seemingly, it’s that simple. And I believe one of the only barriers between a project that will forever languish and a project that will see completion is to overcome this fear of sucking, to work through it, to dodge the inner censor who will tell you you are worthless and have no business writing a fucking book/song/film score, that you should just put it down and do something else. This voice can be very strong and overwhelming, and to tramp it down is no simple thing.

5 August 2012 | guest authors |

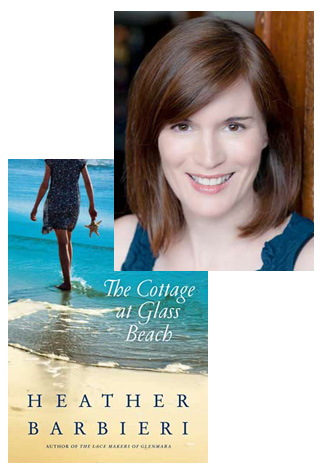

Heather Barbieri & The Novel as Remembrance

All novels are personal, of course, but The Cottage at Glass Beach holds a particularly special meaning for Heather Barbieri. Although the storyline, about a woman trying to resolve a mystery from her family’s past while she’s still reeling from a blow to her marriage, has little to do with Barbieri’s own experience, the novel’s themes of motherhood resonated deeply with her during the writing process, as she explains in this guest essay…

I’d just submitted an outline and sample chapters for The Cottage at Glass Beach to my agent when the news came. My previously healthy, active mother, the woman who was frequently asked what products she used to keep her appearance so young (answer: the old school version of Oil of Olay), had been flown to the emergency room here in Seattle. It took a day or two before the doctors realized she had one of the worst conditions possible, cerebral amyloidosis, from which there was no recovery. (C. a. is a little known member of the Alzheimer’s family of illnesses; there’s no treatment, no cure.) She never regained consciousness and died within a few days—better for her, given the prognosis; hard for us, as it is for so many who find themselves suddenly bereft.

Two weeks later, I had a book deal, but was struggling to get my bearings. As had been happening frequently since my mother’s death, a blue jay perched in the rhododendron bush across from my office window, trilling in what might have been interpreted as encouragement and staring me in the eye. It’s going to be all right, it seemed to say. Whenever I was feeling uncertain it, or one of its brethren, would appear to cheer me up at just the right time. (One of the birds had alighted on the dining room windowsill when we were telling my dad that Mom had passed away, tapping on the glass to get our attention.) Blue had been her favorite color, and the birds became her emissaries, signs and wonders, in a time of need.

17 June 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.