Read This: Begin Again

Towards the end of October, Lincoln Center launched a three-week “White Light Festival” dedicated to “music’s transcendent capacity to illuminate our larger interior universe,” juxtaposing performances of Western classical composers such as Brahms, Bruckner, and Bach with a dance company composed of Shaolin monks or a troupe of Manganiyar siingers from the Muslim communities of northern India. Mrs. Beatrice and I were fortunate enough to attend a “Magnificat” recital by the Tallis Scholars, primarily focused on Arvo Pärt but also including pieces by Palestrina, Tallis, Allegri, Praetorius and Byrd, that was breathtakingly beautiful; I also had the opportunity to attend two panel discussions moderated by WNYC’s John Schaefer on the themes of “Silence” and “Sound,” the latter being preceded by pianist Pedja Muzijevic’s performance of, among other works, John Cage’s 4’33”.

Towards the end of October, Lincoln Center launched a three-week “White Light Festival” dedicated to “music’s transcendent capacity to illuminate our larger interior universe,” juxtaposing performances of Western classical composers such as Brahms, Bruckner, and Bach with a dance company composed of Shaolin monks or a troupe of Manganiyar siingers from the Muslim communities of northern India. Mrs. Beatrice and I were fortunate enough to attend a “Magnificat” recital by the Tallis Scholars, primarily focused on Arvo Pärt but also including pieces by Palestrina, Tallis, Allegri, Praetorius and Byrd, that was breathtakingly beautiful; I also had the opportunity to attend two panel discussions moderated by WNYC’s John Schaefer on the themes of “Silence” and “Sound,” the latter being preceded by pianist Pedja Muzijevic’s performance of, among other works, John Cage’s 4’33”.

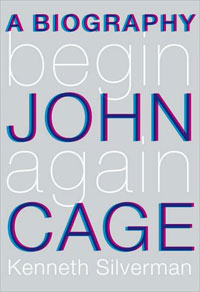

“We often think of sound and silence as opposites,” composer John Luther Adams noted as the event moved into its discussion phase, but 4’33” points the way towards what Adams described as “ecological listening”: “When we start listening to where we are, we hear things that usually we might not think go together, but they do, in the world.” One of the immediate effects of that afternoon’s discussion was to compel me to re-read the chapter on Adams in Alex Ross’s excellent Listen to This, and to start listening to two of his major compositions, Earth and the Great Weather and In the White Silence. What took a little longer was for me to sit down with Kenneth Silverman’s new biography of John Cage, Begin Again.

I was already somewhat familiar with (the concept of) 4’33”, and with the development of Cage’s musical thought up to the point of its creation, thanks to Kyle Gann’s insightful No Such Thing as Silence, but Silverman provides additional biographical context for those early years, as well as covering the second half of Cage’s life. There’s a lot of detail on the processes that Cage used to compose his unconventional works, as well as the non-musical endeavors of his later years, like his eager apprenticeships in chess and engraving. It makes you wonder, perhaps, if intellectual curiosity and boundary-pushing experimentation might be the thread that links Cage to the otherwise seemingly disparate subjects of Silverman’s previous biographies: Cotton Mather, Edgar Allan Poe, Harry Houdini, and Samuel Morse. (Granted, Mather would seem to be the odd man out in that lineup.) Begin Again doesn’t appear to be a substitute for reading Cage’s own essays on music and creativity, but then I don’t imagine it was intended as such—as an introduction to and an engaging invitation to learn more about an important American artist, however, it works quite neatly.

26 December 2010 | books for creatives, read this |

Read This: One Continuous Mistake

Now that we’ve established that you should ignore the NaNoWriMo naysayers, I’d like to share with you two complementary bits of advice I’ve found online and one book that I think get at the heart of the spirit of National Novel Writing Month, for those of you who have chosen to participate in it. A few months ago, John Scalzi wrote a short essay in which the takeaway line (at least for me) was, “Either you want to write or you don’t, and thinking that you want to write really doesn’t mean anything.”

“Do you want to write or don’t you? If your answer is ‘yes, but,’ then here’s a small editing tip: what you’re doing is using six letters and two words to say ‘no.’ And that’s fine. Just don’t kid yourself as to what ‘yes, but’ means.

“If your answer is ‘yes,’ then the question is simply when and how you find the time to do it. If you spend your free time after work watching TV, turn off the TV and write. If you prefer to spend time with your family when you get home, write a bit after the kids are in bed and before you turn in yourself. If your work makes you too tired to think straight when you get home, wake up early and write a little in the morning before you head off. If you can’t do that (I’m not a morning person myself) then you have your weekend… And if you can’t manage that, then what you’re saying is that you were lying when you said your answer is ‘yes.'”

Last year, Merlin Mann offered very similar advice, elaborating on the importance of keeping up your momentum: Start writing, and keep writing! He also warned about paying too much attention to creative writing advice: “When I’m reading about writing, I’m not writing.”

That said, I do want to take a quick moment to plug one of my all-time favorite books about creativity and writing, Gail Sher’s One Continuous Mistake. Its core message is straightforward, best expressed by two of the four “noble truths” upon which Sher builds her advice. “Writers write,” she says. “If writing is your practice, the only way to fail is not to write.” The rest of the book is about opening yourself up to the process of writing and teaching yourself to get out of your own way. The chapters are short, but each one is packed tightly; in a way, the book is more useful as a devotional-like object than as an argument to be read all the way through. Because, after all, you really should be writing.

5 November 2010 | books for creatives, read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.