Author2Author: Nick Antosca & Blake Butler

I first met Nick Antosca a few years back, shortly after the publication of his first novel, Fires. Recently, he let me know about his latest literary project, a satirical novel called The Obese, and then mentioned that Blake Butler also had a new book, Anatomy Courses, from the same independent press. I’d heard a lot about Butler’s earlier work, especially There Is No Year and Nothing: A Portrait of Insomnia, so I agreed with Nick that he’d probably make for a great conversation partner—soon after, I was emailed the following exchange…

Nick Antosca: We’ve probably only met in person three or four times, but we’ve known each other a while via the tubes. And now we have books coming out at the same time from Lazy Fascist Press—both pretty weird books. You co-authored Anatomy Courses with Sean Kilpatrick. Collaboration’s a tricky thing… I have a writing partner for film and TV work, but I’ve never tried it with fiction. How’d Anatomy Courses come about for you and Sean?

Nick Antosca: We’ve probably only met in person three or four times, but we’ve known each other a while via the tubes. And now we have books coming out at the same time from Lazy Fascist Press—both pretty weird books. You co-authored Anatomy Courses with Sean Kilpatrick. Collaboration’s a tricky thing… I have a writing partner for film and TV work, but I’ve never tried it with fiction. How’d Anatomy Courses come about for you and Sean?

Blake Butler: Sean and I had known each other online for a while, I think, and talked a bit, but never really met or anything more than a handful of emails or such. I’d read his work, though, and felt really compelled by his tone and approach to sentences. We certainly shared a certain panache for the grotesque not just of image but of banging words together, I think. If I remember correctly I emailed him and mentioned that it might be fun to try to write something together, just to see what would happen. I don’t think we realized until somewhere in the middle we were writing what basically (in my mind) has the structure of a novel, though one destroyed of most everything but language and a few recurring ideas about the bodies and locations that the nastiness takes place in.

I think I sent him a page that would be the first page of the book in a document and then he wrote what ended up being the second page, and we just took turns like that back and forth over something like 10 months it seems like, each adding to where the other had left off, but always beginning a new page. We always alternated pages, and the way we seemed to take cues in the flow of it was more semantic, often, than plotwise; the ground continued shifting as we went, which made it fun. I learned a shitload watching Sean’s process: he’s a super meticulous editor, and a voracious revisor of his own work, in a different way than I am, and so each time I got the thing back I’d often find he’d gone through and fucked with sentences all throughout his prior parts, stacking them and beefing them out and manipulating the phrasing and the space. Sometimes he’d get so caught up on a single sentence he’d work on it a week and send it back with a note saying he didn’t want to hold me up, and I’d do mine in like an hour and send it back and he’d go into the sauna again; each iteration just kept getting more and more ornate and fucked and I loved it. We both did our thing and stole from each other and smeared each other around in our own passages, kind of forming a structure out of machine shit.

Finally one day he sent one of those couple of sentence sections saying he’d been staring at the sentence for a week and couldn’t stop tonguing it or something, and I read the sentence and it lopped my head off, and that was the end of the book. I don’t think we ever intended to make something publishable really, and I’m surprised we found a publisher in Lazy Fascist; and of course, once that came about, the revision circus went into hypermode for us both, and the book really started to eat itself.

What about The Obese? That book seemed to come out of nowhere for me, after Midnight Picnic. I hadn’t heard you were working on anything and began to wonder and then all of a sudden there was this new novel, seemingly much quicker than the gap between Midnight Picnic and the one before it, Fires?

7 May 2012 | author2author |

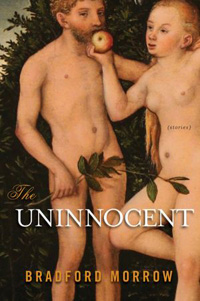

Author2Author: Bradford Morrow & Peter Straub

I had my eye on Bradford Morrow‘s short story collection, The Uninnocent, and Peter Straub‘s short novel, Mrs. God, from the moments (a few days apart) that they arrived in my inbox. I’ve been a fan of both writers for decades, admiring the ways that they’ve applied their literary sensibilities to the themes of horror literature. (Below, Brad invokes the term “gothic,” which in some ways has become to the horror/dark fantasy genre what “slipstream” was to science fiction—a way for literary critics to identify the sophisticated stuff.) What I didn’t realize, but probably should have, is that the two writers knew each other well, and were more than happy to send each other a few questions about these books, and about the fuzzy territory where genre and literary fiction overlap.

Bradford Morrow: As a horror writer who has achieved international commercial success but also stayed true to your serious literary roots, you have often been fearlessly innovative in the way you’ve crafted your narratives. Would you mind talking a little about how you perceive the divide between so-called “genre” fiction and “literary” fiction? My sense is that there is a growing number of serious writers who ignore this critical distinction altogether.

Bradford Morrow: As a horror writer who has achieved international commercial success but also stayed true to your serious literary roots, you have often been fearlessly innovative in the way you’ve crafted your narratives. Would you mind talking a little about how you perceive the divide between so-called “genre” fiction and “literary” fiction? My sense is that there is a growing number of serious writers who ignore this critical distinction altogether.

PETER STRAUB. I’ve been seeing for years that the distinction between genre fiction and literary fiction has been erased by a number of writers whose work assumes that the genre markers can be overlain atop the literary, thereby making the question of a real distinction purely academic. John Crowley and Kelly Link, both of whom began with an at least theoretical attachment to science fiction and fantasy, are the poster children for this tendency. Dan Chaon and Brian Evenson are literary writers whose work falls naturally into considerations of horror and the gothic. For decades. Stephen King has been more or less devouring attributes of the literary stance and using them to expand the possibilities to be found within horror.

Of course many genre writers happily go on using the toolkit/toybox handed to them by previous generations, writing pseudo-Lovecraft stories, pseudo-Sherlock Holmes stories, updated hardboiled novels, etc. This impulse comes from a very common desire to replicate deep satisfactions by echoing the forms and gestures of their sources. Hence the many variations on the Tolkien model for fantasy.These replications, most of which are worthy, are grounded in the desire to create pleasure, suspense, and gratification in the reader. None of them, however, go any farther, so the experience of a prolonged reading of such writers is like that of meeting child after child, brothers, daughters, first cousins, grown-up sons and teenage sons, of the same family. But even the most literary of genre-based writers wishes for a positive pleasurable response from the reader (though it may be for a more complex variety of pleasure than that offered by a Rex Stout novel, Rex Stout being for these purposes an adult son of Sherlock Holmes). There will never be any genre-rooted variation on Finnegans Wake, for example, though I think The Good Soldier is practically begging to be used in this way.

And now, a Question for you, my dear friend: You have demonstrated, it delights me to observe, an unusual openness, for a literary writer of the purest kind, to the possibilities to be found in genre writing, which is most often either dismissed out of hand or patronized by authors of literary fiction. And most if not all of your more recent work has ties to mystery or horror, especially The Diviner’s Tale and The Uninnocent. To me, The Uninnocent is really filled with horror stories, with joyous embraces of any number of horror’s stances, attitudes, gestures, and favored narrativities (a word I think I just made up.) So I want to ask you how you got that way, and what this general artistic evolution of yours means to you. One would think that such a movement would necessarily be toward a general narrowing of focus and intent, but in you it seems to involve a kind of widening-out, a kind of opening to a different Otherness. How could this have happened to a devoted student of Gass, Barth, and Gaddis?

Bradford Morrow: My interest in the gothic—and by extension, horror—dates back at least as far as my second novel, The Almanac Branch, in which the narrator, Grace Brush, may or may not be hallucinating electric-pink light people in the ailanthus tree outside her bedroom window. I co-edited with Patrick McGrath an anthology, The New Gothic, in 1991, which brought together writers as wildly diverse as Anne Rice and Angela Carter, Ruth Rendell and Kathy Acker, Emma Tennant and William T. Vollmann. In other words, the genre writers alongside literary writers, so-labeled. A few of the stories in The Uninocent also date back to the same period in the ’90s, including “The Road to Nadeja” and the title story itself.

Bradford Morrow: My interest in the gothic—and by extension, horror—dates back at least as far as my second novel, The Almanac Branch, in which the narrator, Grace Brush, may or may not be hallucinating electric-pink light people in the ailanthus tree outside her bedroom window. I co-edited with Patrick McGrath an anthology, The New Gothic, in 1991, which brought together writers as wildly diverse as Anne Rice and Angela Carter, Ruth Rendell and Kathy Acker, Emma Tennant and William T. Vollmann. In other words, the genre writers alongside literary writers, so-labeled. A few of the stories in The Uninocent also date back to the same period in the ’90s, including “The Road to Nadeja” and the title story itself.

That said, this is a challenging question, Peter, because in the past my novels fluctuated from mystery/gothic-centered narratives to fairly large scale political/historical “literary” investigations. The more I think about life, I think about it as a very dark place. These latest books also embrace a necessary chiaroscuro of hope and faith. My view of the gothic is that, well, the focus is on evil, entropy, illness mental and otherwise, all things dark. It concurrently and inevitably juxtaposes with good, light, sanity, and so forth. One of the reasons I have become so increasingly interested in the gothic (and even horror) is because it offers me a rich opportunity to explore that ineffable thing that resides in the heart of the most diabolical sociopath, and that is a fundamental, albeit often paltry, goodness.

20 February 2012 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.