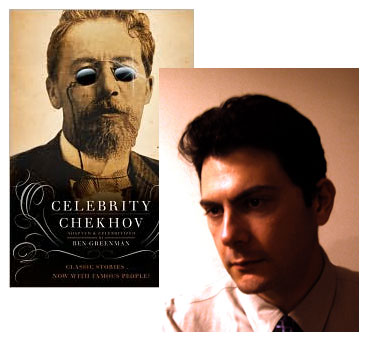

Ben Greenman Revisits Chekhov’s Barber

I’m a big fan of Ben Greenman, and I’ve been trying to get him to do a guest essay for the “Selling Shorts” series for a while. The arrival of his latest short story collection, Celebrity Chekhov, gives us the perfect opportunity. It’s a book with a fantastic, near-Barthelmian “gimmick”: Ben takes twenty-some stories by Anton Chekhov, removes the original characters, and replaces them with contemporary celebrities. (In the story he’s about to discuss, for example, the customer has become Billy Ray Cyrus.) The stories take on new meaning when readers invest them with their acquired attitudes towards the famous personages who’ve been added into the mix—but their original impact is not lost, as Ben explains while telling us about one of his favorites.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again: the others include Mary Robison, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, and Joy Williams. It’s not a long list, this set of regular destinations. There are dozens upon dozens of short-story writers I love, obviously,and nearly as many novelists, and I don’t mean any direspect to anyone else. What I mean, I think, is a certain specific kind of respect to these writers. There’s something in their work that I love stealing. For some of them, it’s the way they kick off their first paragraph. For some, it’s the way they draw characters. For some, it’s the way they manage dialogue. For some, it’s the rhythm, or the boldness of their language, or the clarity of their ideas.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again. This time, I came back to him holding a stick of dynamite, like in a Warner Bros. cartoon. Celebrity Chekhov comes after a series of books that people/critics have read as serious works of straight-faced literature, and because this one isn’t like the others, people are eager to classify it as humor. It isn’t, except in the sense that the original stories are. Sometimes, of course, Chekhov’s original stories were sad, and in those cases I tried to preserve the melancholy, or moral agony. Just as often, though, the originals are comic, perfectly assembled little clockworks of human folly.

Take “At the Barber’s,” an early Chekhov story and one of my favorites. It’s just a touch over 1,200 words, and relates two brief conversations that, between them, take maybe ten minutes. There is only one setting, the barbershop of the title, and only two characters: a young barber and an older customer, both men. But from that potentially claustrophobic formula Chekhov manages to produce a universal tale of hope, greed, and pride. It’s important to add that it’s also an entertainment: the ethical points are made, and made clearly, but the piece never sacrifices its sense of briskness or absurdity.

The story begins early in the morning. The young barber, twenty-three-year-old Makar Kuzmitch Blyosktken, is cleaning up the place, or rather he’s over-cleaning: he’s “perspiring with his exertions” though there’s “really nothing to be cleared away,” polishing spots on the wall that look dull, scraping those that look rough. The barbershop itself mirrors Makar Kuzmich. The windows are also “dingy [and] perspiring,” and the tools of the trade, the combs and scissors and wax, are laid out on a little table “as greasy and unwashed as Makar Kuzmitch himself.” There’s a crushing sense of insignificance.

Then a man comes into the shop. He’s the day’s first customer—and, possibly, the only customer. He’s Makar Kuzmitch’s godfather, an older gentleman named Erast Ivanitch Yagodov, and he’s come a long way to patronize his godson’s shop. It hasn’t been an easy trip, either. Yagodov has been sick with fever, nearly to the point of death—he received extreme unction—and his illness caused his hair to fall out in clumps. On doctor’s orders, he has decided to shave his head so that it can grow back healthy. The barber agrees (though without expressing sympathy for his godfather’s condition), the old man sits down (in one of the story’s funniest lines he asks to be shaved to look “like a bomb”), and the session begins, complete with barbershop small talk. While Makaz Kuzmitch snips away, he asks after Yagodov’s wife and then his daughter. The second question is asked with what seems like insouciance, but after the answer (“My daughter? She is all right, she’s skipping about. Last week on the Wednesday we betrothed her to Sheikin. Why didn’t you come?”) there is a consequential silence that exposes the barber’s deepest motives. “The scissors,” Chekhov writes, “cease snipping. Makar Kuzmitch drops his hands and asks in a fright: ‘Who is betrothed?'”

Yagodov has not misspoken, of course. It is his daughter who is betrothed, to Sheikin, as he has said. The wedding will be held in a week. Makar Kuzmitch puts the scissors down and breaks out in a cold sweat. All at once, he dissolves in recrimination and nostalgia. He tells Yagodov that he has loved him like a father, that he has always cut his hair for free, that he once gave him a sofa. This generosity, Makar Kuzmitch seems to suggest, has been founded on a quid pro quo in which he would be given Yagodov’s daughter’s hand in marriage. Yagodov brushes off this suggestion, after which the barber falls silent and then bursts into tears. He cannot go on, and asks Yagodov, whose head is half-shaven, to come back the next day.

I don’t want to say how the story ends. It’s short, as I said. This piece about it is nearly as long. What I will say is that in the final few paragraphs, Chekhov does wonderful things with humanity. I have not read the story in its original Russian, so I cannot say whether the language is especially beautiful or the dialogue especially organic or the characters drawn with special precision. In the translation, none of these things is particularly true. What is true, what is more than true, is that with language he makes real people: the way they act, the way they wish they weren’t acting, the personal earthquakes that take place along their faultlines, are so perfectly realized that I finish up with “At the Barber’s” with my hands shaking a little bit. The best way for me to judge it is comparatively; so many other writers would have overcomplicated the plot, heaped unnecessary detail upon unnecessary detail, overplayed the moral or, alternatively, laid off it entirely. Instead, Chekhov created a miniature with maximum power. I thank him for it.

Ben Greenman will launch Celebrity Chekhov on Thursday, November 4, 2010, with an event at Brooklyn’s PowerHouse Arena, sharing the spotlight with Neil Strauss and his new book, Everyone Loves You When You’re Dead: Journeys Into Fame and Madness.

3 November 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.