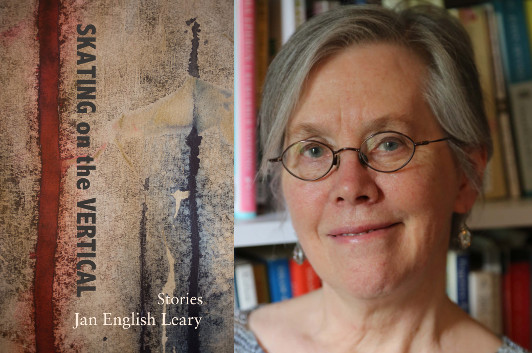

Jan English Leary on Antonya Nelson

photo: John Leary

Many of the protagonists in Skating on the Vertical, the debut short story collection by Jan English Leary, are women on the edge: A young teacher frustrated by a system rigged against one of her immigrant students; a mother desperate to persuade her teenage daughter not to have an abortion; women struggling not to relapse into self-destructive habits in the face of stress. Nobody comes out the other side “fixed,” but they find the strength to push through just the same. In this guest essay, Leary talks about a writer whose emotional depths helped her realize that she, too, not only had stories to tell but could find the means within her to tell them.

I came late to writing fiction, later than most writers. I was in my mid-thirties with two small children and a full-time job teaching French. I’d always been an addicted reader and a lover of language, but it never occurred to me that I could write fiction. I could write analytical essays about other people’s work, but I couldn’t imagine generating stories myself. It was motherhood that brought me to writing, that made me want to explore the intricacies of human relationships through stories.

Back when I was in high school, I read Salinger’s Nine Stories, and my eyes opened to the magic of short fiction. I started reading my parents’ issues of The New Yorker and came to know the work of Eudora Welty, John Updike, John Cheever, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. As a young adult, I loved the work of Ann Beattie, Alice Munro, Tobias Wolff, and Lorrie Moore. But it wasn’t until the early 1990s, after I’d been writing fiction for a few years myself, that I encountered the work of Antonya Nelson in The New Yorker and The Best American Short Stories. In her work, I knew I’d found someone who spoke to me not only as a writer but also as a woman and a mother.

Nelson writes about the power of maternal love, but she doesn’t shy away from allowing her characters to have moments of doubt, regret, even rage and to make big mistakes. She is unflinching in her honesty. No one does a better job than Nelson of populating her stories with families that are broken and cobbled together but bound by fragile yet fierce love. Sometimes these are biological bonds; sometimes they are alliances made of marriage. And with Nelson, there’s always a complicated family web: ex-spouses, in-laws, step-children. But what endures are the bonds of familial love.

In the title story of the collection Nothing Right, Hannah is the divorced mother of Leo, a fifteen-year-old whose eighteen-year-old girlfriend, Niffer, is pregnant and is planning to have the baby. Hannah is clear-eyed about the odds stacked against them, but she stands up to take on the bulk of this new responsibility. No saint herself, she drinks too much, is fired from her job for stealing prescription pads, and does her son’s homework for him. But she is first and foremost a mother who opens her heart to her son’s unlikeable girlfriend and then to the premature baby, who spends his first days in the NICU:

Hannah could only assume that the others shared her mixed feelings about the birth; maybe it would be best if the baby did not survive. It had been created by children, after all, and like other approximate projects—the sugar-cube igloo, the lumpy clay bowl—it was possible that they had not gotten it right; they’d used sticks and buttons, string and papier mâché.

But when she saw the baby—less than three pounds, without tear ducts or eyelashes, lacking the ability to inflate his own lungs—she could not wish him gone. Inside his plastic bin he wailed without sound, miniature body plastered with wires, limbs stuck with tubes, smashed blue face under a clear mask. Leo stood by, Hannah’s son the delinquent, done up in surgical garb from head to toe; he was reduced to a set of floating frightened eyes. He turned on Hannah as beseeching a look as she had ever received.

Alcohol abuse, a depressed, post-partum teen who rejects her premature baby, the unexpected maturity of a teenage boy embracing fatherhood at a young age, a grandmother, worried, yet secretly thrilled and ready to help raise this baby—it’s a beautiful evocation of an unconventional family.

In “Kansas,” from the same collection, a complicated, three-generation family lives together in Wichita. The adults in this story are preoccupied by unwanted pregnancies, unhappy marriages, and hangovers, so they don’t notice for several hours that Kay-Kay, the seventeen-year-old of the family, has gone missing with her three-year-old cousin, Cherry Sue. While waiting to receive news of their whereabouts, Kay-Kay’s aunt Anna, the mother of the toddler and, unhappily pregnant again, thinks about what keeps her in this marriage and this extended family:

Four years ago her [Kay-Kay’s] adolescence had descended upon the household like a lit match in a powder keg. Now the disaster had passed. Gone were the frightening clothes, angry music, Sharpie-marker makeup. Restored was the pretty child who bathed every day and made conversation with her family. Anna sniffed sentimentally. She didn’t love her husband, but she loved these girls. Her own little one had been a factor in the survival of the other. Another baby might wrest another worthy thing from the shipwreck of her marriage; she might once again help aid the greater good. Without Cherry Sue, she and her husband would have gone their separate ways, but now their fates seemed impossibly knotted…. Cherry Sue loved him, and so would the new baby; children didn’t know any better.

Kay-Kay reveals an untapped source of maturity in taking care of not only her cousin but also her grandmother, whom they’ve brought along on their adventure to visit the family homestead before returning home safely in time to scold the adults about their neglect. Despite her youth, she’s the most adult member of the family.

In “The United Front,” from the collection Female Trouble, Nelson writes about Jacob and Cece, a couple who are reeling from the news of their infertility. They decide against all logic to go on a vacation to Disney World where they are surrounded by families with children. While walking around the park, Cece fixes her attention on a mother of five with three older children and twin babies in a stroller. “A breeder,” Cece calls this woman who is also pregnant again. Cece and Jacob fantasize about which of the two babies they’d choose to kidnap. Cece stares at babies in strollers, babies in arms, babies she’ll never have. At one point, the mother walks away from the stroller to take an ill-advised roller-coaster ride, given her pregnancy. Jacob watches his wife head over toward the twins:

Cece was gone, on her way over to the children, striding fast on her short legs, leaving Jacob alone to watch. She waved at the big girls, exclaimed over the little ones. She asked to hold the noisy one, reaching out without waiting for permission.

Jacob steeled himself. If Cece took that baby, he would not only have to hire a lawyer and come up with bail money, but first he would have to pluck the child from her arms. Possibly he’d have to streak after her through the crowds, dashing among the rides and costumed characters—all this nonsense that his wife wants so badly to claim a share of—and bring her to the ground. Security here, he was sure, would be exemplary, quick and efficient, sovereign. It would be of no interest to anyone but Jacob that she had waited for a twin to kidnap, waiting for a baby who wouldn’t be as missed.

It was hot and Jacob’s head seemed cooked. The setting was surreal and thoughts of Crystal Lake had made him feel crazy. Sense was abandoning him. He focused on his wife, who was rocking the squirming unhappy child. She had a way with babies, a rhythm in her hips, a friendly smile. Babies had been stolen from her and she’d had no recourse. Her desire was larger than his, she alone understood its power, the force it had to make her behave less like a saint and more like a human. Watching her now, dizzy with sun and loyalty, Jacob pledged himself to her anew; if she ran, he would not stop her. When she ran, he would come along.

The maternal impulse, all the stronger for being thwarted, fuels this woman’s impulse to act, to take what she wants, to justify her imagined theft. Her husband doesn’t share this desire, but he loves his wife so he decides to support her, to will her success in this crime. The story ends on the brink of a decision. Will she or won’t she?

Sometimes, it’s the most unlikely characters who bind families together. The formerly rebellious teenager shows a gift for nurturing; the boy who can’t get his life together steps up to fatherhood at the age of sixteen; a childless woman contemplates stealing a baby from a woman with too many children. Nelson knows how to regulate the burners under her fiction pot, to let things simmer, then boosting the heat when needed to combine unlikely ingredients which deepen the flavor.

Nelson gives me license to allow the mothers and other characters in my fiction to make mistakes that are bad but not fatal. She challenges me to push them to think unthinkable thoughts and even to say unforgiveable things before gaining a measure of redemption. As a writer, I am inspired to take risks, to step outside my fear of failure. As a mother, I recognize a kindred spirit.

11 December 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.