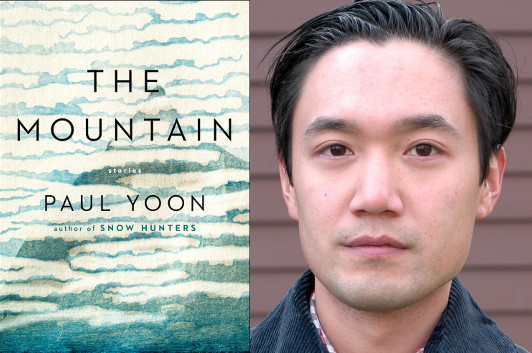

Paul Yoon’s Character-Building “Island”

photo: Peter Yoon

It hardly seems like it’s been three years since Paul Yoon won the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award for his first novel, Snow Hunters, let alone seven years since he was tapped as one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” young writers of imminent distinction. Now here he is with his second story collection, The Mountain, a half dozen stories set in locations around the world, from the outbreak of the First World War to the near future. Each of Yoon’s locations, whether it’s the shattered landscape of post-WWII Europe or the rundown housing for Shanghai factory workers, is vividly detailed, in ways that dovetail neatly with the characters’ behavior—in this world, you feel, these people surely would do these things. In this essay, Yoon tells us about a short story that helped him get to that place in his writing.

I discovered a writer named Alistair MacLeod when I was around twenty-one years old. He passed away a few years ago, but he was known for his work set in Nova Scotia and also for his great slowness. His entire career spanned, I think, two short story collections and a single novel. I read his stories first, and one in particular, when I was first attempting to write, changed the way I thought about craft and how to compose fiction. It’s called “Island,” and it centers around Agnes, a woman living alone in her old age in a small house on a small island off the coast of Cape Breton, which itself is an island, though she calls it the mainland.

The story begins with Agnes by the window of this house one rainy October day, waiting. What she’s waiting for we don’t know. The entire first paragraph describes the rain falling against the window. Then she moves to stoke the fire in the stove and to keep herself warm. That is the entire second paragraph, which consist of long descriptions of fire and burning wood, etc. We begin with lengthy descriptions of rain. Then we move to fire. We wait some more for a few more pages, within the confines of the house, and then interestingly from there the story unspools and goes back in time, all the way to her birth and traces the narrative of her entire life.

What never occurred to me until later was that MacLeod wasn’t writing about rain and fire, not really, but about the protagonist: her character, her mind, her physicality—that he was using the initial setting of a house, the window, and the stove, to introduce us to her state of mind and her life. In the first paragraph the rain on the window is at times aggressive, almost violent; at other times delicate, almost fragile.

We see later how this becomes such a core part of Agnes’ life, this duality of near-violent hardship, her strength, and also her great vulnerabilities, loneliness, and sorrows. The window is also described like a curtain at the entrance to another room, a room she cannot enter, and already we feel this imprisonment, this inability to look out past the blurry rain, to look outward and take a step forward metaphorically and literally.

Instead she, and us, turn around and look inward, farther back into the room, toward a stove and a fire. This fire that contains ancient nails that twist and blacken in the ash like bones. And because the story goes back in time from there I think what MacLeod is doing in this moment is opening a door for her to think of everyone she has lost in her life, her loved ones, her demons and ghosts. So that the nails that have survived the fire are lampposts in her memory.

What I learned from this story many years ago was that setting, location, furnishings, all those details—the house, the window, the stove—weren’t simply decorations for creating a fictional world. They were instead integral to creating a character, more specifically, creating a point of view, and view of a world. The house wasn’t there because MacLeod simply needed a house for Agnes. He needed that specific house with that specific rained-on window and the wood with nails burning in that stove. In this way we begin to have a sense of Agnes, perhaps before we’re even aware of it. This is what fully imagined, richly layered fiction means to me. A sentence and then another one doesn’t exist solely to push, say an event or scene forward or to, again, create a setting because you need one.

How lovely it was, and continues to be, to discover this. To discover that with this craft, we’re responsible for making every sentence as dynamic and as close to the character’s world as possible so that what we hope to create is something closer to a living organism on the page. For MacLeod, the story is set in that house alone, on that island, with rain on the window, the fire, burning wood and nails. But that place he has created, with such respect, is her.

20 August 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.