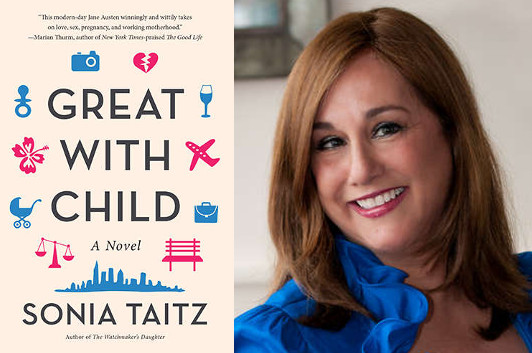

Sonia Taitz’s American Dream

photo: H&H Photographers

I first met Sonia Taitz back in 2012, when we recorded an episode of Life Stories to discuss her memoir, The Watchmaker’s Daughter. Since then, she’s been focusing on fiction, and her latest novel, Great with Child, actually explores some of the same psychological and emotional themes that she previously wrote about in autobiographical mode. But, here, let Sonia explain it…

The heroine of Great with Child is the daughter of two newcomers to America. Driven by her parent’s immigrant ambition, Abigail Thomas becomes a blindly competitive associate at a prestigious law firm. Her background provides a baseline for her personal and professional evolution through the course of the book. The catalyst for change is her accidental pregnancy, which throws all her certainties into question. My own trajectory led me from law to writing—and to writing this book in particular.

I’ve always proudly defined myself as the daughter of immigrants. And not just in the vague, melting pot American way, but as a first-generation child, born of refugees of World War II. My parents came out of war-torn Europe and sailed the ocean until they saw the Statue of Liberty. That statue meant everything to them, as did its poem, written by Emma Lazarus (also born of immigrants): “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

They were tired, they were poor; they had been huddled and incarcerated. Now, they were leaving the Old World to embark on the New. In their eyes, I was destined to become the embodiment of their American Dream, with all the security that entailed. Loving them as I did, I faithfully wanted whatever they wanted. It would be years before I could differentiate my wishes from theirs—or even knew what my own wishes were.

My parents were Holocaust survivors. Both had been born and raised to early adulthood in Lithuania. When the Nazis invaded, they were segregated, ghettoized, and imprisoned in concentration camps. Only a tiny percentage of their communities remained after the war, and my mother and father, now homeless and penniless, were sent to Displaced Person (DP) camps in Germany. There, they applied for asylum and new citizenship in America. After years of waiting, they came to New York and met each other—at the less than romantic-sounding Lithuanian Holocaust Survivors Ball. Both were good looking and great dancers. They fell in love, married, and started a family.

From the start, I was expected to be studious—both my parents’ educations had been cut short by the war—and the mandate for me was to be “successful:” no easy task in a religious school that had a double English-Hebrew curriculum. From age four, I was in class from early morning until late afternoon, loaded down with homework. My father, a watchmaker who’d learned his trade at the tender age of thirteen, said that he wanted me to be “with the brass buttons,” the ones in authority: the kind that most people associated with professionalism, prestige, and most precious of all, security. So, given my love for language and Talmudic argument, law school seemed like the logical choice after college. The other kids in my neighborhood, with similar refugee and immigrant backgrounds, became doctors, lawyers, accountants, teachers, and business owners.

We knew we lived to make up for our parents’ insecure beginnings. We knew we would spend our lifetimes working to ensure that they, and we, never knew the fear of hunger or displacement again. When I passed the bar, I began working at a Wall Street firm, heading—like Abigail—for partnership as a litigation associate.

I say this not to brag, but to stress how rigid and remorseless my path was. It was the only path I knew—until other factors lured me away from the vertical climb of corporate America.

And yet the American Dream that my parents had for me was not the one I wished for myself. Eventually, my love of words (and disdain for twisting them into legal arguments) forced its way to the forefront, and I embarked on a career that is the antithesis of security. Becoming a struggling author was one sharp demotion; parenthood took me even further away from the world of ambition and status. I fell definitively off the fast track when I had children—but moved closer to the dream that I was developing for my own life, the path of compassion, selfless devotion, and greater ethical clarity.

I can tell you that my parents were not too happy when I stepped off the top-career treadmill and embarked on the insecure path of being a writer. “Can’t you do it as a hobby?” my mother pleaded, as my father hinted that if I ended up at The New York Times, it might be okay. But my creative career fell to the wayside as I raised my own family. My mother had worked as an assistant to my father while raising my brother and me, so she must have found it strange that having a brood at home made me less willing to keep up with my ambitions—even as a writer.

For me, having my byline in the paper (even the Times), a magazine, or a new book, paled by comparison to caring for my children or, at that point, tending to my parents—both of whom developed cancer. I was lucky that my husband’s income was adequate for our family, and was long past the point of wanting the prestige of “brass buttons.” I realized, over and over, that nothing can replace the hours I spent fielding my children’s questions about life, nor the months I spent by my parents’ sides before their deaths.

When my ailing father once asked me, “Isn’t there anywhere more important you have to be? Some important work you have to do?” I could honestly answer, “No.” My own children, who often observed these difficult times, understood what I meant. And their love taught me as much as my own taught them.

What, after all, is the American dream? Is it merely to get ahead and become rich and powerful? Or, perhaps, is it the freedom to lean backward and into the embrace of your past and your family as you nurture your future? These are some of the many questions Abigail Thomas explores in Great With Child. Love, after all, is the source of the message my own parents gave me. They wanted me to be as safe and sure as possible, so that I would not suffer the injustices that they endured. I’m grateful to live in a much better place than they did; that was their ultimate gift to me as immigrants to this country. And while love and art have provided me neither safety nor sureness, they continue to offer the most precious kind of security—that of knowing you are living for what really matters.

24 April 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.