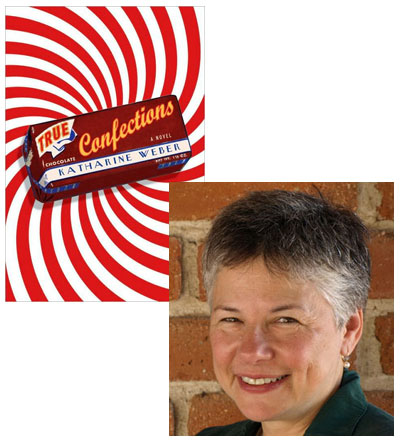

Katharine Weber Is Keeping It Unreal

I just started reading Katharine Weber’s new novel, True Confections, in preparation for her appearance next month (Monday, January 11) as part of the author/blogger discussion series I curate for Greenlight Bookstore, the independent shop that recently opened in Fort Greene. (I’m only introducing the evening’s discussion; Weber will be interviewed by Levi Asher of Literary Kicks.) In the novel, Alice Tatnall Ziplinsky purports to be telling the history of Zip’s Candies, the Ziplinsky family business, but it is immediately (and amusingly) apparent just a few pages into the first chapter that for all Alice’s insistence on the “truth,” there’s an agenda at play. Now, as somebody who grew up seeing the Schrafft’s sign from the highway driving through Boston growing up, I suppose there’s a bit of me that wonders if Zip’s is based on any real family-owned candy business… but Weber would like to remind us that such questions are, for the purposes of fiction writing, rather beside the point.

To write a novel is to engage in an invented reality over an extended period of time. The willing suspension of disbelief that we expect from our readers has to start with the writer’s own willing suspension of disbelief beginning with the first intentions about the novel. Over the months and years of writing, as the novelist willingly and gladly dwells in this alternate realm every moment she spends wrestling with sentences (and for most other waking hours as well, spent away only from the physical task of writing it down), the world of the novel looms larger and larger, becoming more and more specific and vivid.

This conjured reality doesn’t cease to exist when the novel is finished. The opposite is true; full knowledge of these people in this time and place, and all its verities, is deepened through the revision process. Editing and then copy editing offer fresh challenges to the author’s authority to justify the information, stated and implied, of the novel’s internal logic. Whether it is the consequence of the way gravity reverses with every completed rotation around its three suns on the planet Zorth, or the telltale moment that occurs in the middle of a peculiar ritual of birthday party toasts practiced by a family in rural Kentucky during the Civil War, the integrity of the invented reality must be deeply known and experienced by its inventor in order to succeed. Writing a novel is a kind of extended phantom tour of duty in this other place, even as we go about our ordinary lives.

Once the book is out in the world it can be quite disturbing when this reality is resisted and misunderstood by readers. The willing suspension of disbelief is necessary to the fundamental transaction between the reader and the writer—in exchange for a willingness to believe, the reader gets to be entertained by the novel. But the contemporary reader seems these days far less willing or able to transact business with the authors of contemporary novels that are not magical, set in the distant past or future, or filled with vampires.

It is confounding to be quizzed by readers who are avid to connect the dots that will reveal the “real” parts of one of my novels, the elements that are actual, and, ideally, personal to me in some way. There is satisfaction in identifying that earned information, checking off another landing point of comprehension along the way. Those personal, actual, identifiable parts are perceived as having greater value than the rest of the novel, the fictional fiction, the parts I merely made up. The act of reading a new novel has become for many readers, perhaps especially those in book groups, like decoding an encrypted message. There is an urgency to this task, this reading of the novel “correctly,” in order to make deductions about everything that surrounds the novel. It is assumed that insights about the author and the author’s intentions are hidden here and there in the pages like Easter eggs under a bush, waiting to be collected. Is running it all to ground the new goal of reading fiction, solving this puzzle, cracking this case, squeezing all the juice out of what is really in a novel?

Why? Where is the sheer pleasure of being transported by what one is reading? Where is that willing suspension of disbelief? Is reading for pleasure not a worthy activity in itself? Must novels be packed with high fiber information in order to be judged sufficiently intellectually nutritious? When did characters in novels become less interesting to us than the author and her relationship to the novel?

“Make imaginary puissance,” exhorts Shakespeare’s chorus at the start of Henry V: “Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them.” How handy, to have that instructing chorus. I wish I had a chorus to guide readers before they turn the first pages of my novels. Mine would say something like this:

O Reader, make imaginary puissance! Use your imaginative powers, think, when we talk of anything at all, that you see it! Accept it, let your mind’s eye see what it is in the novel, and do not strain to make it something in our reality instead of the novel’s reality. Please do not expend your imaginary puissance trying to discern that which it is “really” based on, and who is the actual person who inspired that character, and which events really happened, and did the author have that childhood, that mother, that friendship, that betrayal, that triumph, that disappointment, that tragedy? O Reader, please do not expend your imaginary puissance constructing from the novel the outline of the author’s life! Take pleasure! Let the novel be the novel!

13 December 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.