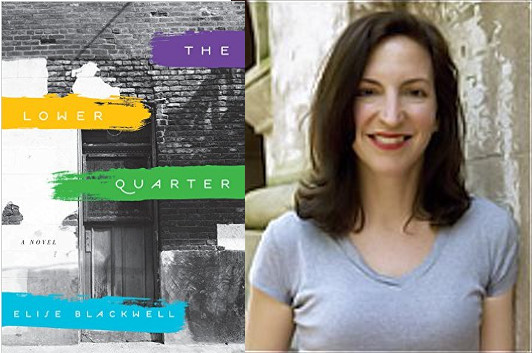

Elise Blackwell: Two Writers, One House

photo via Elise Blackwell

I’ve been a fan of Elise Blackwell for years, even before we ran into each other at a literary festival in Montgomery a few years back. So I was glad to hear that she has a new novel—The Lower Quarter—out this fall, and delighted to be able to run this guest post where she talks about sharing a literary vocation with her husband, David Bajo.

When I finished the first novel I would publish, I showed it to my husband. He’s also a writer. I first fell in love with him through the obliquely romantic critiques he wrote for my short stories when we were both students in the same graduate fiction workshop—critiques that started with epigraphs from Kant or definitions of Zeno’s arrow. Which is to say: I care what he thought. I was nervous.

“I finished your book,” he said one morning about two days after I gave him the manuscript.I wanted the speed with which he read it to mean something, but the truth is that it was a very short novel and he’s a very early riser. I waited. Maybe I lifted my eyebrows, but mostly I waited what seemed like a very long time.

“You write very clearly,” he said. And that was all he said then.

Clarity is a desirable trait in prose, but I had been hoping for a word more along the lines of beautiful or moving or great, perhaps even perfect. I can hold a grudge, and more than a decade later I’m not above retelling this story when we argue or I’m just trying to get my way. I can be funny and self-deprecating; usually when I tell this story it’s a comedy and not a drama.

When I see a link to a story called something like “Ten Reasons Not to Date a Writer,” I always click the bait. I read and nod. Yes, we’ll see your most person experiences as material and, yes, we’re always criticizing the narrative structures of movies you’re enjoying. Put two writers together in a romantic relationship, and it can be a cesspool of subject theft, insecurity, and jealousy. The divorces are often ugly—all the more so for their brilliant articulation and even more so when they’re chronicled in print.

Almost every morning—every morning that it’s not raining and both of us are in town—my husband and I walk our dogs. Our house is a comfortable bungalow squatting on the dividing line between two neighborhoods, one funky and one posh. When we walk left among the mix of owned and rented houses and duplexes, property values stay pretty much the same. When we walk right, they escalate quickly. We each tend to walk left when alone, but together we usually go to the right. The dogs know this and pull that way. We choose it because there’s less traffic and wider walking space, which is better for getting lost in conversation without endangering a canine.

We don’t look like writers, and this isn’t a “writerly” neighborhood. We sometimes talk about the usual things that most couples do, from our daughter’s college aspirations to how soon the house absolutely has to be cleaned. But most often—and these are the best mornings—we talk about the work we mostly don’t show each other anymore. We should have figured it out before we did: smart advice can often be the worst advice for a particular book. And, yes, sharing drafts is a potentially marriage-endangering activity. Even abstract talk isn’t always safe. I can be callous in my humor and once inadvertently talked my husband out of a novel he’d started by making a crack about its subject matter.

Usually, though, there is great comfort in sounding out a plot problem or an idea about structure to someone who understands what you’re talking about, who is sympathetic to the endeavor of working on a multi-hundred page work of fiction, generally for several years, while also working and living a life. It’s this comfort that has kept us married even when other things have not gone well. But it’s more than comfort; it is respect for the work and how it’s done and the person doing it. And it a good reason to be married to a another writer even if you never show him a page of unpublished work.

9 November 2015 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.