Lenore Myka’s Tough, Scrappy Old Ladies

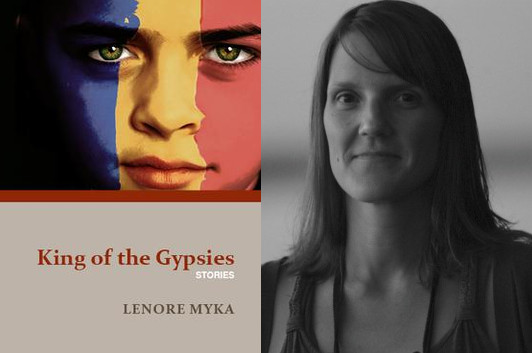

photo via Lenore Myka

The stories in Lenore Myka‘s King of the Gypsies are rooted in an uneasy intersection of American and Romanian culture, with characters from each nation struggling to make sense of each other and of their experiences. As she wrote, Myka explains in an interview, “I just tried to keep in mind what I knew about my friends’ lives there and what I had observed and experienced as a Peace Corps volunteer living at essentially the same standard as my colleagues and friends. I tried to be empathic but also true to what I inherently felt about day-to-day living in a post-communist country.” In doing so, her stories are set in often brutal circumstances, but, as she mentions in that same conversation, “ultimately my stories are about resilience, and in resilience there is always hope.” In this guest essay, Myka reveals some of the other writers who’ve helped her understand how to create characters with the kind of complex resiliency you’ll find throughout this collection.

When people unfamiliar with but desirous of reading short stories ask me to tell them my favorites, my brain goes blank. Ask me what I least like—now that’s a much easier question to answer. But a favorite anything—color, food, hobby, place—unnerves the generalist in me. Doesn’t it depend on the weather, the day of the week, whether or not you’ve had your morning cup of coffee, your mood?

Sure, there are the usual suspects: “The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien; “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” by Katherine Anne Porter. Lorrie Moore, Stuart Dybek, Deborah Eisenberg or, further back, Chekov, Mansfield, Faulkner, Hemingway. I’m leaving dozens of my favorites out here; the list becomes unruly. Lest we get cynical about contemporary literature, there are, in fact, many great short story writers, old and new, out there. There will no doubt be many more to come.

The frustration and beauty of being a writer is that you are always learning. My own writing projects/puzzles often determine my current list of favorites; these favorites become my teachers. Right now, I am studying character and so am obsessed with Grace Paley, Jane Gardam, Mavis Gallant. I like tough, scrappy old ladies because I hope one day to be one. Mostly, I feel that I am trying always to write towards these authors, to emulate in my own work something that might distantly echo the near-perfection they achieve.

As an MFA student, I was taught that in a short story every detail, word, description, and punctuation mark must count; if it doesn’t, if it is superfluous or indulgent, cut. This is much easier said than done, but if anyone comes close to realizing it, Paley comes closest. She fits an entire life into a single page, sometimes a single paragraph or sentence. Consider the start of her story “Wants”:

I saw my ex-husband on the street. I was sitting on the steps of the new library.

Hello, my life, I said. We had once been married for twenty-seven years, so I felt justified.Here is voice, character, in the most succinct of moments. “Hello, my life” says the narrator and I cannot help but think: Who is this person that these should be the first words she utters?

Gardam is better known for her novels but has written several collections of short stories. Even her novels possess something of the short story about them, weaving individual narratives that might have otherwise successfully stood alone. In fact, one of her stories, “Old Filth,” is also a critically acclaimed novel of the same name; both short and long forms explore the life of a Raj Orphan barrister nicknamed “Filth” (“Failed In London Try Hong Kong”).

Like Paley, nothing is unnecessarily included in Gardam’s stories. You will not see her wasting space on the physical description of a character unless it provides some essential insight, as it does when Filth recalls his nemesis, Veneering: “…great, coarse, golden fellow, six foot two, with his strangled voice trying to sound public school.”

Gardam demonstrates how when a writer really understands her characters, she need not spend an excessive amount of time explaining them to the reader. From this simple description we understand that Veneering is a man out to prove something, but that he is also a threat to Filth. Here too is plot and tension, compelling me to read on because I want to know: Why does Filth despise Veneering so much?

As for Gallant, I’ve never understood why she isn’t included on those many Bests lists, why her stories aren’t thrust upon young writers. I was dumbfounded when faculty advisors admitted to never having read her. My favorite collection of hers, Paris Stories, should be required reading for all students of the short story.

I suppose most young writers have an author who teaches them how rules may be broken. I’ve had a few, but Gallant has possibly taught me more than most. She uses exposition when others might have demanded scene. She is not afraid of politics, though her stories are not overtly political. Like her Canadian cousin, Alice Munro, she can fit an entire life into twenty pages, beginning with birth, ending with death.

What I love most about her stories, however, is that she is not interested in creating likeable characters but those that most closely reflect real people. She exposes prejudice and judgment, insincerity and pettiness, scraping away layers to reveal the underlying paradoxical complexity that is being human. A story of hers I read often is “Mlle. Dias de Corta,” whose narrator is both ignorant and intelligent, charming and a bore, xenophobic and accepting.

All of these authors are sharp observers of human psychology, understanding intimately what motivates and deters us from having the life we desire. As writers, they all teach me about character and in this way, teach me what it means to be human. Their characters are hypocritical, oxymoronic, flawed, conflicted, fickle, unpredictable. They are like the very best and worst people I have ever known; they are like me.

11 October 2015 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.