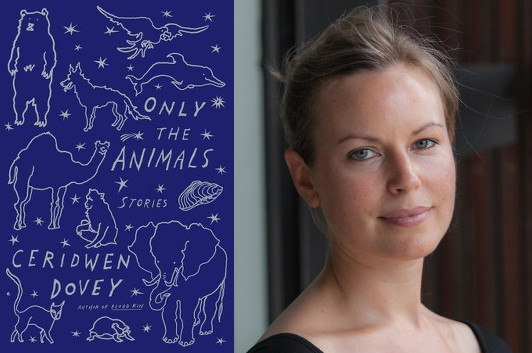

Ceridwen Dovey: Colette’s Ultimate Outsiders

photo: Shannon Smith

As Ceridwen Dovey notes in this guest post, not only are the stories in Only the Animals narrated by animals, but each story draws upon a different writer for inspiration. A camel accompanies the Australian short story writer Henry Lawson on a fateful desert trek, for example, while Himmler’s dog, taking on his master’s enthusiasm for Hesse-inflected Buddhism, struggles with feelings of confusion and failure after being rejected. Dovey’s ability to take up different voices, and to make each feel utterly convincing, reminds me in some ways of the stories of Jim Shepard—a sense of strangeness and familiarity in equal measure. Here, she describes how one of these stories, in which Colette’s cat is stranded on the Western Front during the First World War, took shape.

Each of the stories in Only the Animals is told through an animal narrator who has died in a human conflict of the past century. Right from the beginning of the project, I knew that writing from an animal’s eye view was territory that many, many other authors had covered. The parrot story was the first I wrote, and at the time I was reading J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals, and while doing research for the story I went back to the original Flaubert story about a woman’s relationship with a parrot, A Simple Heart.

I was searching for a way for the stories not to be relentlessly depressing. So I decided that each animal soul should also pay tribute to an author who has worked in this symbolic space before—and in this way put a bit of hope and humour in the stories, to signal that some of our best writers have tried to find a way to say something meaningful through animal characters.

I knew that I wanted to write a story set in the trenches during World War One, when many of the soldiers at the front kept pets—cats, dogs, rats, pigeons—to keep up their morale. I’d heard a story about the French turn-of-the-century author and music hall performer, Colette, having had a close relationship with her cat, but I’d never read her work myself. I went to the library and took out every book by her that they had on the shelves.

What an absolute delight to discover her wry animal narrators! In the same way that Virginia Woolf would, a couple of decades later, play with the conventions of literary biography in Flush by telling the life story of the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning through the voice of her spaniel, Colette was experimenting with voice by writing imagined ‘dialogues’ between her pet dog, Toby Chien, and pet cat, Kiki-la-Doucette, in columns for a Parisian newspaper in the early 1900s. She also wrote a whole set of stories told mostly from the perspective of various animals, many of them written at the start of the Great War. The collection, Cats, Dogs and I: Stories from La Paix Chez Les Bêtes is now very difficult to find in an English translation. The only one I could find is the version translated by the Princess Alexandre Gagarine in 1924, and published in New York by Henry Holt.

In the collection are many monologues by cats: Tomcats, Persian cats, a cat “with a sad life;” there are also many by and about dogs: a jealous dog, addressing his Master; a dog for sale by a Dog Fancier (“I am that most forlorn thing on earth—an animal for sale,” the dog says); a confession from a small dog who “chased a huge cat, tore to bits a greasy newspaper exquisitely scented with rank bacon and fish.” There is also the tale of Lola, a greyhound who keeps her owner company in the dressing rooms of the music halls in which she performs. Near the end of the collection is a story Colette wrote in the spring of 1914, about the Antwerp zoological garden, a moving meditation on the fate of the caged animals (“Some may say that men are no better off… But man is a puny creature at best, dazzled and killed by the solitude of freedom”), and stories told by a human narrator about a squirrel and a pair of snakes. In “The Man with the Fishes,” the narrator meets a travelling performer at the train station who carries about with him a glass jar containing three goldfish, which he swallows over and over, then regurgitates, alive, after half an hour, for audiences in the countryside.

What I love most about Colette’s animal stories is their playful, skirt-high view on the world. It’s alienating to gaze through an animal’s eyes, but Colette’s animal narrators look at the pageantry of human life with wonder and irony, and their tone alternates between tender and tongue-in-cheek. The stories, taken collectively, remind us of how irrelevant the dramas of the human world can be, but also pay tribute to the strange empathy that exists between animals and humans. They’re often very funny (even to a modern reader). The language Colette uses in them is extraordinary: poetic, sparkling, crisp. Here, for example, is the voice of Poum, “the devil cat,” from the beginning of the collection:

In the beginning you found me amusing—I made you laugh. You still laugh, but with a growing uneasiness. You laugh when at meal time I appear bringing in my mouth a cockchafer from the moor—a cockchafer round and marbled like a plover’s egg,—and proceed to eat it ferociously—crunch, crunch, crunch—and empty its fat insides with such disgusting relish that you turn aside from the plate where your soup grows cold. For you I unwind, in graceful festoons, the bowels of the chicken you are to have for dinner tonight… I eat anything: flies, crabs, a sole lying dead on the sands, the glow-worm gleaming like a steel circlet in the grass.

The Latin root for the word “fable” means to speak, to give voice—and the way Colette does this for her animal narrators honours all animals in our original relationship to them, when we still thought of them as oracles, seers, creatures with magical power. Her style acknowledges our eternal ignorance about the “other.” James Wood wrote of the Portuguese fabulist José Saramago (who also often wrote about animals) that he narrates his fables as if he is both wise and ignorant. Colette does something similar in her animal stories, playing on ideas of innocence and knowledge, but above all affirming the quiet power of storytelling through animals, the ultimate outsiders.

15 September 2015 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.