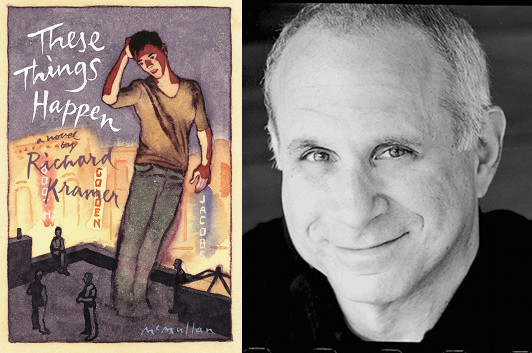

Richard Kramer & The Threads of These Things Happen

photo: Dick Avery

Richard Kramer, a writer/producer for television shows like thirtysomething and My So-Called Life, describes his debut novel, These Things Happen, as “a story about a modern family, set among Manhattan’s liberal elite.” It turns out, however, that some of its characters have deep roots in his experiences on the opposite end of the country, including the things he learned when he realized he’d been taking a key figure in his day-to-day life for granted and decided to do something about it…

The birth of the book goes back twenty-five years, maybe even more. When we were doing thirtysomething, it was so exhilarating and exhausting I wouldn’t drive home at the end of the day, but I’d go instead to an Italian restaurant a few blocks from my house. I did this four nights a week, often alone so I could work on scenes for the next day. The place became a habit, and I went there even after the show’s five years came to an end; they knew me.

The person who knew me best was the man who was combination captain/maitre d’/manager. He was around forty, dressed in a blazer and striped tie, always smiling and with some nice thing to say. I would call from the set and say I was coming in, and he’d say “Great, Richard. Do you want the patio tonight, or your usual table?” When I’d get there he’d show me to my seat and immediately send out some delicious plate with a few free somethings. Looking back, I calculate I had at least a thousand meals there, which is a lot of carbonara. And—here’s how These Things Happen comes in—I realized when the restaurant announced it was closing that I didn’t even know this man’s name. Maybe I knew it once, but what did it matter? He was there to be a prince of the pleasant, dedicated to making my life a little bit nicer. He didn’t need an identity beyond that.

Seeing this shocked me. Here I thought I was such a nice guy! But I wondered: How many other people do I render invisible because it’s too much trouble to endow them with a biography? And how many people do that to me? Why do we, unconsciously, but still with some selective design, limit our imaginations about those around us?

So I wrote him a letter. He called me, and we agreed to meet for coffee. He told me he just assumed that no one knew his name, and if they did it was a nice surprise. I asked him about his life, which turned out to be rich, and complex, and happy, in ways I’d never have guessed and couldn’t have invented (and I was supposed to be a writer). He shared the inside details of how restaurants worked. And he said I could use anything he told me, however I wanted to.

His name was George, and that is how George, one of the main characters in my book, got his name. The details of George’s life in the book aren’t those of George’s life in life (I hope that’s not too confusing). But they were the seeds of a character—one who still needed a story of his own in which to live.

That took a while. I can’t even say I was searching. A writer’s shelf is crammed with homeless characters waiting to be rescued by stories, and not every character finds a home. It took a few years for the next piece to fall into place. When we were doing My So-Called Life, we’d see a hundred kids a week in casting sessions, looking for those naturals who might have that translucent quality we’d been so lucky to find in Claire Danes. One day a boy came in, read for us, had an interesting quality that didn’t quite fit the role for which he was auditioning. As he was leaving he turned to us and said, “How come there’s never a story about someone who’s got a gay dad?”

That night I went home and wrote three pages of this kid talking. The speech began: “My dad is gay. I don’t think I am, but apparently gayness can swoop down on you when you’re old, like a buzzard. No one asked for my vote in this situation. Whatever. I told my dad I loved him even though I thought he was out of his mind. ‘Not to be annoying’, I said to him, ‘but do you have any explanation for all this?’ And he just sighed and said to me, ‘I don’t know. I guess these things happen.’

The actor came back the next day, read the three-page speech with no preparation, and was superb. We took it to ABC, who felt the story wasn’t “relatable,” which meant the notion of gay families hadn’t yet appeared in the culture. They did say they’d consider it for Season Two, which was a lie. But it didn’t matter, because we never had one. The young actor’s name was Wesley. He became my model for the young kid, Wesley, in the book.

So I now had two pieces of the puzzle I didn’t know I was beginning to put together. Then, five years later (I know these dates as I’ve consulted my journal), I went to a friend’s house for dinner in New York. I was seated next to a woman who was a big deal editor at a big publishing house. We talked, enjoyed each other’s company; she struck me as being perhaps the most evolved person I’d ever met, not to mention the one with the nicest shoes; she was on the side of every possible angel. At the end of the night, we rode down together in the elevator. I told her she seemed perfect. “Is there anything about yourself that you’re ashamed of?” I asked. I don’t know what gave me the courage to do that; I’d never asked it of anyone before. I instantly tried to apologize, but she had something she wanted to tell me. There was something, yes. She had a fifteen-year-old son. She had many gay friends. And she would not be comfortable leaving the kid alone with any of them. “And I hate that about myself,” she said. (That’s pretty much word for word from my journal). “And I’ve never even said it out loud before.”

She didn’t realize the gift she’d given me. Because now I had three characters: George, Wesley, and Wesley’s mother, Lola (that was not this lady’s name). And I had an itch, to do something with them, to come up with a story in which they could all live and bump up against each other. Everyone else followed easily, husbands, stepfathers, and friends. And I shouldn’t leave out that the last magic ingredient was a story someone told me about the teenaged son of a friend who had come out in a school assembly—not after an election, as in the book, but after winning first place in the tenth grade talent show.

And we were off. It started to simmer. I played with these guys in a script for a short film, pitched it (unsuccessfully) as a TV series, tried it as a play. Then one day (although it was in truth over the course of many days) this trio, joined by Wesley’s ballsy, courageous friend Theo, walked into my office and said: “Look. We’re a book. Take a chance.”

I took it. And here, what seems like a century later, we are.

15 June 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.