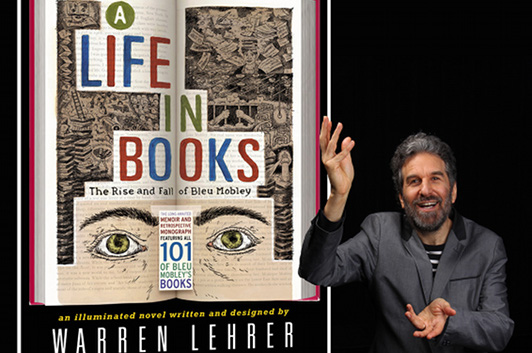

Warren Lehrer & the Bleu Mobley Oeuvre

photo and illustrations via Warren Lehrer

Warren Lehrer’s guest essay stems directly from a question I posed to him when I invited him to write about A Life in Books, a question that tackles the way it addresses the life of a fictional writer not just through that writer’s words, but his book jackets. “What drew you to telling a story through a mosaic of imaginary books?” I wanted to know. This was Lehrer’s response.

(By the way, all the artwork you’ll see below—and much more besides—is also part of a traveling exhibition that has often included a performance/lecture by Lehrer. Something to keep an eye out for…)

My previous five books were all non-fiction: four portrait books about eccentric Americans who each straddle the wobbly line between brilliance and madness, and Crossing the BLVD: Strangers, Neighbors, Aliens in a New America, written with Judith Sloan, which documents 79 new immigrants and refugees from all over the world who live in Queens.

After representing all these real people and their stories, I felt a need to work on something that gave me more room for invention, and allowed me to get at the interior world of characters. I started looking at all these book ideas I had scratched into notebooks, and drawers full of short stories and interior narratives I had written. And somehow, this peculiar, well-meaning if ethically challenged writer character emerged—Bleu Mobley—who was presently in prison looking back on his life and career.

Instead of just writing his story, I decided to combine his reluctant memoir with a retrospective monograph of all 101 of his books including their cover designs and ‘first edition’ catalogue copy. But the covers and catalogue descriptions didn’t satisfy my curiosity about my protagonist’s creative output, so I began writing book excerpts (that read like short stories). The excerpts started cluing me into aspects of Mobley’s life (people, scenarios, motivations) that I hadn’t anticipated. Some book titles that I thought came early or late in his career turned out to be middle period works, and vice versa. My Bleu Mobley life events/bibliographic timeline chart kept changing. As the puzzle of Bleu Mobley’s life revealed itself to me piece by piece, the relationship between an artist’s life and his or her work emerged as a major theme.

In the memoir part of A Life In Books, Mobley claims to have never written about himself, yet we discover him and the people he loves sleucing through all his books, however obliquely.

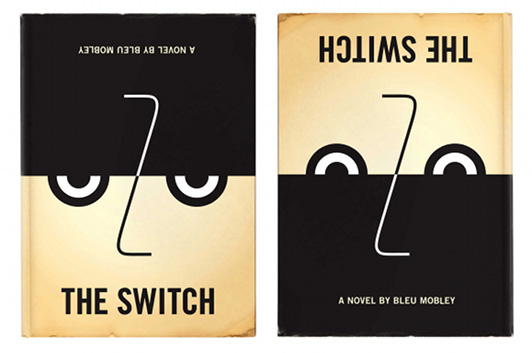

After a two year stint as a foreign correspondent reporting on overt and covert wars, Bleu writes his first novel The Switch, which takes place on a day when everyone on earth is switched with their number one nemesis.

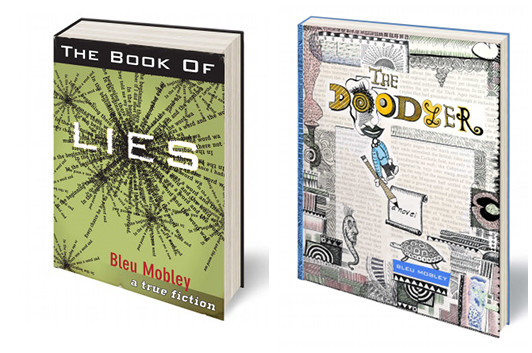

The Book of Lies is a thinly veiled novel based on Bleu’s best friend, a self proclaimed liar and devout atheist who swears he’s telling the truth and nothing but the truth, so help him God. Inspired by Bleu’s mother, The Doodler is a novel about a compulsive doodler who loses all touch with reality and falls inside one of her doodles.

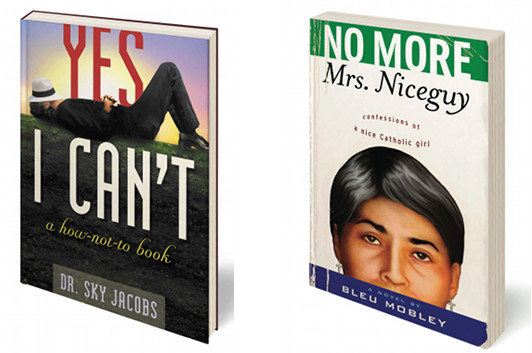

After a disc disease in his back finally catches up with him, Bleu faces reality—he’s a full-time writer in a part-time body. He writes a self-help book under the name Dr. Sky Jacobs, marketed as a slacker’s guide to NOT accomplishing your full potential. Later, influenced by his daughter’s experience as a patient with a serious blood disease, he writes a novel about a dutiful, God-fearing woman who is diagnosed with cancer and discovers her voice through the transformative power of hard-earned rage.

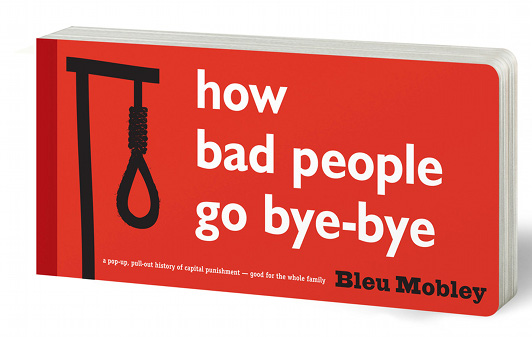

Bleu’s five-yea- old daughter asks about an execution she hears about on TV. Wishing there was a book he could use to help explain, he writes How Bad People Go Bye-Bye, a pull-out, pop-up book on the history of capital punishment.

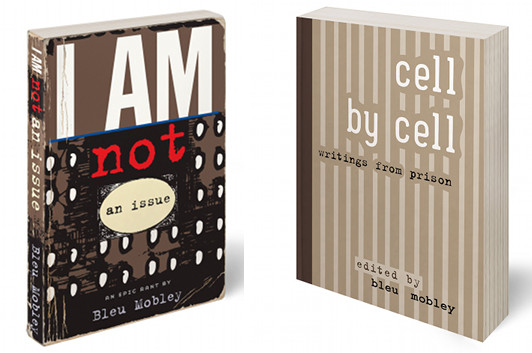

Three paragraphs of an otherwise positive NY Times review of a gallery exhibition of Bleu’s mother’s art is devoted to her mental illness and the “long tradition of madness and art.” Bleu feels terrible seeing his mother contextualized in this way and considers his own culpability inventing characters and representing real people to highlight causes. In prison, Bleu starts a “literacy program” as a means of survival. He grows to love the men in his prison writing workshops and admire the heart, soul and wisdom he finds in their writings.

In addition to Mobley’s 101 books published as an adult, A Life In Books documents his very first books composed and printed in the letterpress shop of his junior high school where he first fell in love with printing, words and books. I also had a lot of fun writing and designing personal letters, newspaper articles, reviews of his books, and other “artifacts” that help tell Bleu Mobley’s not-so-simple story.

This mosaic you refer to, Ron, ended up being a great vehicle for me. It not only gave me the opportunity to flesh out the connection between my author’s personal relationships and the characters and stories in his books, it also gave me a platform to reflect on a half century of American/global events. I empathize with all the characters in A Life In Books, who are portrayed as complex and contradictory people dealing serious issues, but I have no problem lampooning institutions such as the medical industrial complex, the publishing industry, mainstream media, pop and celebrity culture, and U.S. foreign policy. In that sense, this novel is both very funny and dead serious, which is pretty much how I experience life to be.

In his article in The Atlantic, Steve Heller equated the structure of A Life In Books to a Russian Matryoshka doll. In The Brooklyn Rail, Robert Berlind wrote that it was like a Chinese puzzle. I can’t help but think of 1001 Arabian Nights—the ultimate collection of stories nested between the covers of one book. Scheherazade kept telling stories in order to survive, which is true of Bleu Mobley (and a lot of writers). Throughout his life, Bleu composed books either as a way of making sense of the world around him or to fill in the holes/transform loss and sadness into art. He’s in prison for refusing to reveal the name of a confidential source of a book he wrote about the president of the United States (43). After nine months in prison he decides to tell all.

Now it’s up to each reader to decide whether Bleu Mobley is an important man of letters or a sell-out, a champion of the voiceless, or an elitist hypocrite, the conscience of America, or an ungrateful traitor; and if his story is a parable of the rise and fall of a culture, or a swan song to the book itself as a medium.

9 June 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.