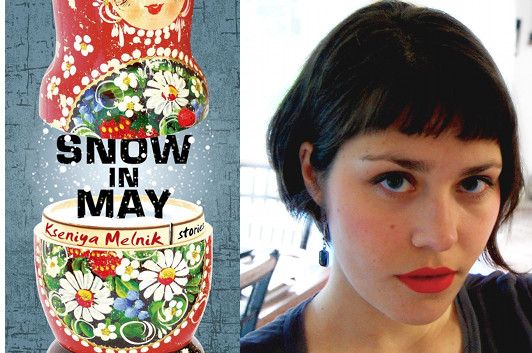

Kseniya Melnik and the Long Short Story

photo via Kseniya Melnik

Kseniya Melnik was born in the northeastern Russian city of Magadan, which also serves as a home base for the characters in the stories that make up Snow in May, her debut collection. Their experiences span late Soviet and post-Soviet history; she jumps back and forth over decades from one to the next, but it’s not jarring, because each story is captivating in its own way, immersing us in an equally compelling interior drama. Another side effect of that immersion is that you won’t notice how long some of these stories are—for, as she explains in this essay, Melnik has learned to give her stories the space they need, and we’re the ones who benefit from it.

Ever since I became serious about writing stories, my drafts have consistently come in at over what is considered the page limit for the standard American short story—twenty-five pages, or about 7,000 words. This seems to be the magic number, at least according to most contest rules, literary journal submission guidelines, syllabi of college creative writing workshops, and MFA application requirements. The stories in The New Yorker mostly adhere to that length or less, and the compact stories of Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff, John Updike, and Lorrie Moore still wield great influence around the workshop tables of America.

For many years, I chopped my stories down to bare bones to submit to contests and journals only to see the drafts grow back all that meat (and some descriptive fat) in the next revision. Even in the MFA workshops, where the submission guidelines were expanded to “as long as it needs to be,” my drafts were the longest in the class.

I always turned in my forty-pagers with a plea for help to choose what to cut. Usually, my classmates’ suggestions were superficial—fifty words here, a hundred there. To fit into that key length of twenty-five pages, I would have to re-imagine the scope of the story, cut scenes, whittle down characters. An occasional recommendation was: write a novel out of it! But I was convinced that what I had on my hands were definitely short stories and not summaries of novels or even compressed novellas.

While I don’t doubt that my stories needed to be trimmed, I’ve made peace with the fact that most of them lean toward being a povest’, a form that has a stronger tradition in Russia than in North America. Povest’ is defined as a narrative with a word count somewhere between a short story and a novel. The classic povest’ concentrates on one character’s struggle with several obstacles during a limited passage of time and contains very few secondary characters and subplots. Some of the famous examples of this genre are: “Olesya” by Alexander Kuprin, “First Love” by Ivan Turgenev, “Poor Liza” by Nicolai Karamzin, “Heart of a Dog” by Mikhail Bulgakov, and “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” by Lev Tolstoy.

The English term used most often for povest’ is a novella or a short novel. But to me, those indicate a narrative that would be comfortable in a separate book, like George Orwell’s Animal Farm, John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, and, recently, On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan. (Though, the decision to print something as a stand-alone book is as much a commercial issue as an artistic one. Zadie Smith’s hardcover of “The Embassy of Cambodia” is just 73 pages.) Yet I feel much more comfortable calling “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” a novella than, say, “First Love,” mostly because of the length. (There is, technically, a term for something between a short story and a novella—a novelette. However, nobody seems to use this term seriously outside the science fiction and fantasy genre.)

And so I return to my understanding of povest’ as a long short story. Incidentally, according to Wikipedia’s Russian-language entry on povest’, in the early 19th century the label was applied to everything that wasn’t long enough for a novel, including short stories, making it a much more flexible definition. The more widely I read, however, the more I realize that even though there isn’t a word for povest’ in the English language, there are many excellent long short stories. One of my absolute favorites is Alice Munro’s “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage”—a masterpiece of 18,000 words. There’s also Munro’s fifty-page-long “The Albanian Virgin,” Lorrie Moore’s “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain” and, of course, James Joyce’s “The Dead,” at over 15,000 words.

Reading these amazing long short stories has taught me that the decision to cut (or expand) should be based on the individual story’s needs rather than some arbitrary word maximum, even if it limits the number of venues that would consider that piece for publication. I now worry a bit less when my first drafts arrive at over 10,000 words. I will be curious, though, to see the final page count of my first novel. Somehow I very much doubt that my publishers will listen to the reasoning that Tolstoy’s War and Peace is over twelve hundred pages.

19 May 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.