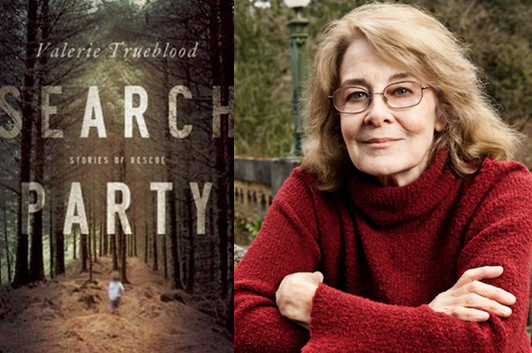

Valerie Trueblood & Salter’s People

photo: Lucien Knuteson

Longtime Beatrice readers may recall Valerie Trueblood’s first guest essay, in which she celebrated the short stories of Eudora Welty. Trueblood has a new collection out, Search Party, its stories linked by the theme of “rescue,” interpreted in all sorts of ways. Stories like “Downward Dog” and “Think Not Bitterly of Me” are finely honed character studies, and though it’s not quite right to say it’s a “pleasure” to get inside these characters’ heads, it’s a revelatory experience. And Trueblood is here to tell us about another writer she admires for his character work…

This is the short story’s moment, we hear. Yet when will reviewers stop awaiting a “full-length” work? When will “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” rise up to petrify the hand about to type the word “miniature”? When will the story call in its chips as a form? When will it come out?

All the talk is about James Salter’s new novel All That Is, but there must be many readers like me who have been reading and thinking and marveling for years over his uncanny gift for the short story form.

The charge has been made, with this new novel, that his characters look down on women. Setting aside the possibility that those making this discovery in his work have not read anything else written by a male, we may note that in fiction as in life the sexes often look down on each other. Salter does indeed say things like “There was not much more to her than met the eye,” but his louche women are more likely to remind us of Jean Rhys’s, and of her men, for that matter, than of Hemingway’s women. These men of his who say the women they meet are “too human” are not at ease, they suffer for what is missing in themselves, or what’s extra and has them in its power: the craving or fetish, the sometimes ruinous allergy to the commonplace or routine, a frozen loneliness, a hankering for both sexes, an outgrown love still “in the great central chamber” of their lives. The verb love is most often in the past tense.

The wonder is that so much of the delight of existence, ecstasy really, can flow under and through such accounts.”Character” is the wrong word for Salter’s story—men and the women with whom they exchange hurts. Where short stories are concerned, the word “character” seems to me overused. We can say “character-driven” about a novel, but the short story is generally bent on something else with its inhabitants, and Salter is a master of the powerful leashed figure held in the cage of the form. His people are recognizable humans, though more beautiful than most, but so briefly seen that the awful aura of the life on its way to them includes us in a way we would not have imagined when we met them a page or two before.

They come alive in so few words. The haunting “Akhnilo,” in which a mystical sound draws a man into his breakdown—”it seemed he was the only listener to an infinite sea of cries”—is seven pages long. “My Lord You,” a longer story but just as spare, will stay with me always. A sad woman falls in love with a strange dog. The dog is at once itself and its dissolute owner, who has rudely touched the woman at a party and laid open her whole psyche. That’s too simple, of course, for the hypnotic action of this story, in which her mysterious failure to feed the starved dog is more gripping to the reader than any of the story’s human relations and the dog more moving than many a character given hundreds of pages in a novel. The story begins at a dinner party Fitzgerald could have written, or Katherine Mansfield with her sharp eye and bitterness, but ends in a region of no explanation, of Beauty and the Beast in some primal form before it was a fairy tale.

In his sweeps of time and change, you can feel the intoxication the restricted space offers a formalist. A friend back from Rome was just telling me about her first sight of two paintings by El Greco known to her only in reproductions. She had thought she would stand looking up, as one does with El Greco, but these two scenes of the life of Christ were small. Small from across the room. They grew in the sight: they were bursting with their narrative. The Salter short story is like that. In the beauty of his rooms and cafes and roads, the beaches where his people lie on their backs and talk to the sky, in his mercilessness to them and his icy aesthetic, he is our Flaubert.

5 August 2013 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.