Read This: Thieves of Book Row

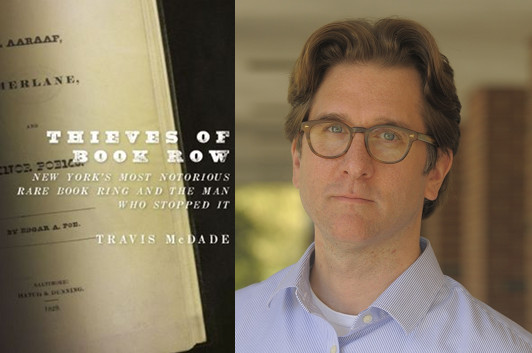

photo via Travis McDade

Recently, I did an interview for Shelf Awareness with Illinois law professor Travis McDade about Thieves of Book Row, his history of how the New York Public Library (among other institutions) took on a network of professional book thieves that targeted libraries across the northeastern United States, filching early Americana and other important first editions, often selling them to Manhattan book dealers. There’s a lot to talk about in this book—more, in fact, than I could fit into the Shelf Q&A. So here’s a bonus excerpt from our exchanges…

You’ve written that “getting away with [book theft] is harder than ever” today. A century ago, how seriously did the criminal justice system treat theft from libraries?

Everything I’ve written, and am writing, has punishment as a component—not surprising since I come at this from the legal perspective first, and the special collections perspective second. So I think about this a lot, and it’s more complicated than people think. It has always been, and remains, a question of getting the authorities to treat it seriously. In Thieves of Book Row I showed that, if libraries get a good prosecutor and an understanding judge, there will be significant punishment for these crimes. (Sing Sing prison!) Otherwise, it’s the traditional slap on the wrist. I’m happy to say that it is not as bad as it once was, but it is still true to an extent. Prosecutors have an incredible amount of discretion when it comes to these things. They need to be shown how important these books, documents, maps and manuscripts are. When that happens, we see good results. When it doesn’t, we get probation.

Another thing I show in the book is that the press, a hundred years ago, was a lot more draconian in its attitude toward these thieves. Newspapers, reflecting public sentiment, advocated punishments of the sort that—how shall I say this?—would not pass Eighth Amendment muster. By the latter part of the 20th century, on the other hand, newspapers routinely announced punishment for theft of extremely valuable books with a lame joke about library overdue fines, and just as routinely trotted out the canard that these thieves were suffering from bibliomania.

Is that why libraries would frequently decide not to report stolen books to the authorities?

I think there is a lot to this. Some of it is embarrassment, some a desire to avoid bad press and some an unwillingness to irritate donors. But there is also a natural tendency to not make a big deal out of something, as long as the material is recovered. This is particularly true with libraries that have seen cupcake sentences for thieves in the past—they think, why bother?

Thieves of Book Row is a lively history about the criminal underworld underpinning the “high culture” collector’s market of rare books in the early 20th century, filled with great stories about the thieves, the dealers who profited from their activities, and the librarians who decided they’d had enough. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

9 June 2013 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.