Joelle Fraser & the Return to Memoir

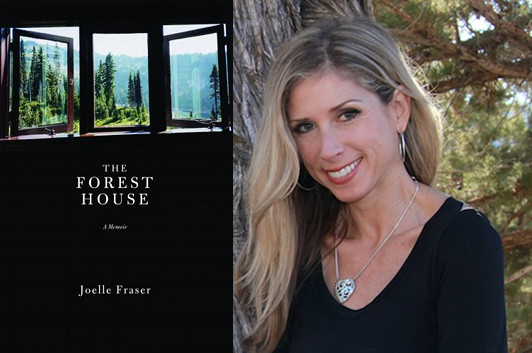

photo: JoelleFraser.com

In The Forest House, Joelle Fraser writes about life after the breakup of her marriage, when she moved to a remote town in California because it was as far as she could get away while still being close enough to make joint custody of her son workable. It’s the second time that Fraser’s put her life under the literary microscope, and in this essay she discusses what it’s like to re-subject herself to her own scrutiny—and, ultimately, of course, the scrutiny of others—and why, in the long run, she couldn’t stay away.

After my memoir, The Territory of Men, was published by Random House in 2002, I swore I’d never write another. Writing that book—a sprawling coming of age chronicle of my childhood in the wild California of the 1960s and ’70s and its effects on my adult life—nearly killed me.

Naively, when I turned in the final draft, I thought I was done with the hard part. I wasn’t prepared for the surreal pendulum effect of the memoir: after years of solitary, grueling self-reflection—you’re then hauled out into the public eye for months of astonishing exposure.

That’s the difference with memoir—sure, the fiction writer has the private/public dichotomy as well, but the memoir writer herself is just as much on display as her book. And so I discovered—as did my family—that reviewers often focus on the life rather than the writing of the life. (For instance, one well-known critic described my multi-married parents as “cancer cells uniting and dividing.”)

There’s really no way to prepare for the judgment—both good and bad—from the world. Writing can be hypnotic, can’t it? While bent to the page you can forget that most people don’t write books—especially not in the genre of memoir, which for the average person is akin to flashing yourself on Main Street.

Another uncomfortable discovery: at readings, I found that memoir writers tend to attract the lost and the needy, who sometimes see you more as a therapist than an artist.

Why would I put myself—and my family—through all that again?

So for nearly a decade I wrote fiction, or tried to, reaching the 50-page mark a few times. (Those dusty drafts, I think, are stacked in a drawer somewhere.) Then, in 2010, having left a marriage and lost half my son’s life to joint custody, I escaped to an isolated forest retreat, a house on the edge of the world.

What got me through the next year: the wilderness out my door, and the words I wrote in my journal. I’d moved in in January; by June I knew I had a book, which eventually came to be The Forest House: A Year’s Journey into the Landscape of Love, Loss and Starting Over.

Armistead Maupin said he writes “as a way of processing my disasters.” I suppose that’s what I do, too. There’s something addictive about getting to the heart of what haunts us. That’s why I read memoirs, certainly: to see how another survived some challenge.

When The Forest House was published, it struck me that I wasn’t alone in writing a second, more focused memoir. One glance at my own bookshelves tells me that: there’s Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life (1988) next to his wartime experience in In Pharoah’s Army (1994). Next to his books are Mary Carr’s The Liar’s Club (1993) and Cherry (2001), about her adolescent years, and most recently Lit (2010). On the next shelf sit Augusten Burroughs’ Running With Scissors (2003) and his addiction memoir Dry (2004). Nearby are Jeanette Walls ‘s The Glass Castle (2006) and her “true-life novel,” Half Broke Horses (2010), about her grandmother.

Even novelists do this, don’t they? The first novel is often accused of being a veiled autobiography, in which the author’s life is revealed through the prism of the novel’s characters. Steve Almond wrote recently in The Missouri Review that whether in nonfiction or fiction, “You’re always writing about your family. You circle the same shit over and over again all throughout your writing career.”

The goal, it seems to me, is to dig deeper with each piece of writing, to uncover more nuance, more insight, and to bring it higher into the light. I’m not enjoying the exposure with this second memoir any more than I did the first time, but I’m proud of the book. My mother calls it “memoir grows up,” and she has a point.

For me the dedication in my two books sums up their real difference. My first book was dedicated to my immediate family. In The Forest House, I chose to dedicate it to “children everywhere, and the parents who love them.” I wanted the second book to help others who were going through divorce, or custody issues. It wasn’t a book about understanding the past, but about finding a way through today, and tomorrow.

I’m at work at something new—for now, I’m calling it a novel.

20 May 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.