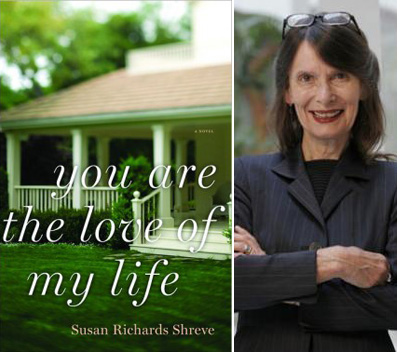

Susan Richards Shreve & The ’70s from Here

photo: David Carmack

The material that got sent along with my copy of Susan Richards Shreve’s new novel, You Are the Love of My Life, mentions that the story is “inspired by Shreve’s personal connection” to its setting in early 1970s Washington, D.C. So when it came time to suggest possible guest essay topics, expanding on that personal connection seemed like a good choice: What was it about that time and place that Shreve drew upon in telling the story of a children’s book author who brings her son and daughter back to her family home in D.C., then finds herself caught in an emotional tug-of-war with a neighbor that threatens to reveal the hidden shames of her past? Shreve was happy to explain.

Oh, by the way: When she mentions having started up an alternative school with her husband? Folks who’ve been reading Beatrice for a long time might recall that her son, Porter Shreve, wrote about his side of that story in another guest essay…

On January 28, 1973, the Paris peace accords were signed, ending the war in Vietnam. My husband and I had turned thirty and were living in north Philadelphia—three young children in a big, old house shared with a facsimile of a commune. That night my husband took our five-year-old son to the candlelight gathering in honor of the end of the war. It was a moment of victory that over the years has faded to defeat but at the time for young men like my husband who had been waiting to be dispatched to southeast Asia, the spirit on the streets of Philadelphia was joyous. And the spirit in our house was one of adventure bordering on chaos.

The commune had been travelling in a VW van from Colorado to Vermont by way of Philadelphia and was delivered to our doorstep whole cloth by my younger brother. They never made it to Vermont and so we lived in relative harmony with a large vegetable garden in the yard, pot luck parties every weekend, daily hikes along the river, a general sense of satisfaction. Or malaise.

My husband, brother, and I and some other teachers had a grant to start an alternative school which we called OUR HOUSE. We had been given a building by a wealthy do-gooder in the neighborhood, had gathered about a hundred students to take courses organized on the basis of the power of choice such as Alternative Life Styles—a course team taught by my brother and me in which we examined other life styles that our students might be interested in choosing: homelessness, for example. Or a life with the Hare Krishnas where we spent a couple of dizzying days. Or one on a river raft going down the Shenandoah, living in tents, finding our food in the woods.

We had a craft cooperative where students threw their own pots, made macramé dreamcatchers, hand made books of their own poems and sold them to their parents on Saturdays. They made the furniture for the house, the desks from telephone spools, the chairs were pillows. Friday nights there was a coffee house with guitars and mandolins and on the third floor of the school where my brother lived with a photography teacher, we had a half way house for runaway middle class students and druggies. We were the beginning of the future. Or so we believed imagining this moment as ours.

Not long after, we moved to Washington, D.C. (the alternative school closed for lack of funds) to another big house with boarders to help pay the rent.. My husband had become a family therapist, a new discipline. I was writing novels and teaching in the English Department at a suburban university. We lived in the neighborhood where I had grown up in the 1950s, sent our children to the schools where we had gone and though we belonged to vegetable coops and babysitting coops and transformed our neighborhood into our family, we were raising our children against a backdrop of racial unrest and violence, of the public lies of Vietnam and Watergate , the resignation of Richard Nixon. Not without hope but certainly chastened by experience.

In retrospect, the 1970s were years of becoming. We were more casual than our parents had been, less authoritative, more intimate in our relationships with our children. Families as a unit were in the process of changing, no longer the nuclear family in lock step as mine had been, but large groups of parents and children with community dinners of baked lasagna, homemade bread, Gallo wine. Marriages were more open and not infrequently splintering. There was great social change—results of the Supreme Court decision of Roe v. Wade on abortion, the declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness, the civil rights movement for women, for African Americans. In the middle of my marriage to my high school sweetheart, I felt as if I’d drunk pink punch laced with alcohol or powder served up at college parties. My small world was rushing into a kind of social revolution for which I was unprepared.

21 October 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.