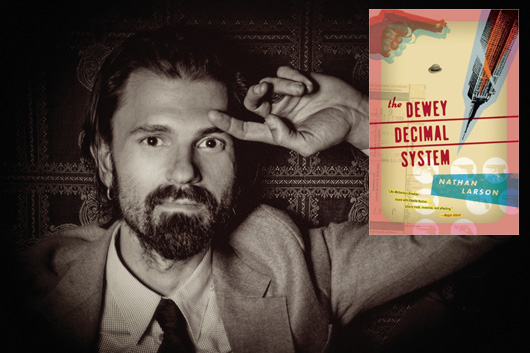

Nathan Larson: Diving into Dewey Decimal’s World

Akashic Books

I’d made tentative plans earlier this summer to interview Nathan Larson for one of the Beatrice ebooks, and when we couldn’t quite get our schedules to sync up, I knew I still wanted to get him talking about his first two novels, The Dewey Decimal System and The Nervous System—the opening salvos in a “dystopian noir” series set in a post-disaster New York City, where an amnesiac veteran who’s taken it upon himself to safeguard the main Public Library building gets dragged into a bunch of other messes and, as your noir heroes do, pushes at them over and over until he provokes traumatic outbursts. If you’re not from the city, you’ll have to take my word for it, but Larson gets the street-level details meticulously right; even in post-disaster condition, you could navigate the city by his descriptions, no problem. (The scope of what happened to the city—and the world—is unclear, though there are hints throughout the two books of a string of coordinated incidents; there are also several hints about Dewey’s pre-disaster past, though those clues haven’t quite gelled together yet.)

Here, then, is Larson’s take on his shift to fiction writing after (or, rather, in addition to) a productive music career that includes playing guitar for Shudder to Think back in the ’90s and subsequently composing film scores.

Y’all, I am brand spanking new to this writing game, and don’t pretend to have any answers with respect to how it’s done. Like any creative endeavor, it seems to have something of the esoteric about it, and when it flows it feels very much like one has tapped into some sort of cosmic cloud of information for which the author serves as conduit. There’s nothing new about this description; greater minds than mine have waxed upon the subject. It’s exactly the sensation I’ve experienced working as a musician, so I’m not a stranger to this thing—but I find it fascinating to observe this phenomenon at work regardless of the medium.

Of course this kind of hippy shit occurs about 5 percent of the time, and the other 95 percent is pure slog and persistence. It’s work, it’s a jobby-job. And this too is exactly like making music. If I’ve learned anything about writing, whether I’m speaking about prose or film scores or songs or whatever, it’s that you have to sit down and do it, and you have to finish it, and it will suck, and then you go back and make it not suck, to the degree that you are willing and able. Seemingly, it’s that simple. And I believe one of the only barriers between a project that will forever languish and a project that will see completion is to overcome this fear of sucking, to work through it, to dodge the inner censor who will tell you you are worthless and have no business writing a fucking book/song/film score, that you should just put it down and do something else. This voice can be very strong and overwhelming, and to tramp it down is no simple thing.

After two novels (and half of a third), I have no particular formula or working method. I sit down without a plan and whatever bubbles up bubbles forth. I know folks for whom this approach functions very well, and I have likewise been told I am doing it all totally wrong and nothing of value can come from this m.o. This is very likely true for some folks, and perhaps my work is suffering from this lack of an outline/grand plan, but it’s the only way I know to get it done. So I do it.

Fortunately, I came into this writing thing with a set of parameters, making it all the easier. I knew from the outset I would be doing a “genre” thing, a “noir“-ish thing, and genres come with a set of rules to play by and play with, which was perfect for a first-time novelist. I was essentially commissioned to write The Dewey Decimal System by my friend and publisher Johnny Temple, who is an extremely clever guy. With no evidence that it would be a successful experiment, as I’d never written a book, Johnny asked if I might have a shot at a “noir” kind of thing. As I had no ambitions in this direction and therefore nothing to lose I gave it a go, and apparently, in a minor league kind of way, it worked out. I fully realize how goddamn lucky I am in this respect, and am so thankful my friend Johnny gave me this chance to try this fancy hat on.

The character Dewey Decimal was already with me, I didn’t really need to conjure him. He is a mash-up of people in my family, folks I’ve known in different contexts, friends who have been lost to me. He in many senses (and strictly in my view) one possible embodiment of the modern American collective psyche: violent, nostalgic, phobic, angry, nationalistic, narcissistic, paranoid, emotional to the point of sappy, and yet empathetic, vulnerable, charitable, and deeply kind in surprising moments—fundamentally “moral” in the very special manner the character defines “morality.” We might not regard him or his actions as “moral,” but by his subjective view of himself, Decimal believes he is generally doing the right thing.

He himself is a victim/end product of an awful construct Will Self calls the “man-machine-matrix”, which conditions populations—including, I contend, much of the United States—to love and seek to please their abusers/captors à la the Stockholm Syndrome, to swear allegiance to the very system that is destroying them, and to generally allow themselves to become debased out of fear. It is to be debased and raped, and then sincerely thank your rapist. This is consistent with the intellectual disconnect that allows the most vulnerable members of our society, who are essentially cannon-fodder and scrap to the Man, to be the most vicious defenders of a mechanism that has placed them in this most unfortunate situation. It is as it has always been, in that the serfs who have suffered great abuse at the hands of their masters, offer up their lives in defense of their master’s house.

Allowing for a bit of my far lefty sensibilities to creep in, I have tried to keep the character apolitical. That’s been tough, and I’ve largely failed there, I reckon. I see these books as satire and social commentary. They’re also pulp in the truest sense, meant to be left behind on airplanes and trains after a fast read. In The Nervous System, I’ve had a huge amount of fun deconstructing (or sloppily executing, depending on your perspective) one of my least favorite genres, the “techno-thriller.” It’s my feeling that shows like 24 have been designed, at least on some level, as pro-torture/pro-preemptive attack propaganda. They allow us to say “Well hey, what was Jack Bauer gonna do? They had his daughter and they were gonna kill her and the bomb was going to go off so off course he had to cut that guy’s finger off…,” etc., etc. They make an extremely complex conversation cartoonish and simplistic.

In one respect, I am aware that I am contributing to the vast mountains of crap in this subspecies of “literature”. There’s something fun about that, though it makes me feel cheap. I can only trust my gut and hope that in approaching this material with a smile and a critical perspective I’ve learned something, and left little touches of insight and subversion to be discovered in these books, however modest.

At the very least I can say I am learning how to write and like any skill, intend to keep chipping away at it. Thanks for reading this and have a great day.

5 August 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.