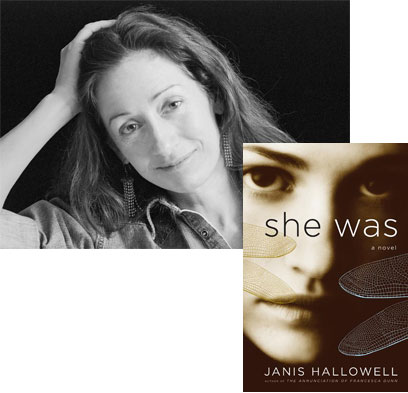

Janis Hallowell on Giving Fiction Life (and Fiction Giving Life)

Janis Hallowell’s She Was comes at an interesting moment—not only has former SLA member Sara Jane Olson, one of the real-world starting points from which the novel takes its own imaginative trajectory, been back in the news this year when she was briefly paroled and then hastily re-imprisoned, we’ve actually had a bumper crop of novels about radicals on the run this season; see Peter Carey’s My Illegal Self and Hari Kunzru’s My Revolutions. In this essay, Hallowell explains how a work of fiction can start with something real, then teach its author about imagination’s power to inspire compassion.

She Was has been called ambitious. It felt ambitious to write. But as happens with ambitious projects, I learned a thing or two. Writing She Was, I got to redefine my interpretation of “writing what you know.”

The main story—18 year old student radical Lucy Johansson protests the Vietnam war by setting a bomb at Columbia University that kills a man after which she goes underground for 34 years—is one that was inspired by the lives of several real women, and similar stories had already been written. That’s pretty intimidating, but nobody had written about a student radical fugitive who is arrested during the Iraq War era. The chance to explore the correlation between the Iraq era and the Vietnam era through a story that naturally brought the two together was irresistible.

Because I was only fourteen in 1971 when the catalyzing event took place, the story required me to write about things I don’t know first hand, yet there are millions of people alive who do. Also pretty intimidating. As the book took form and the historical aspects gained importance I imagined my in-box clogged with emails pointing out what I’d gotten wrong in the timeline. I imagined reviewers accusing me of being unqualified to write about something I hadn’t lived through. But I chose to stay with the project because I felt strongly that since Vietnam was the formative trauma of the baby boom generation and generations since, and the chickens from that time were coming home to roost in this decade, I had to join the conversation.

The breakthrough came on the day I realized that Lucy’s brother, Adam, was a Vietnam vet and that his cognitive difficulties due to MS caused him to flash back to Vietnam. I got really scared. “Oh my God,” I thought. “I’m going into combat in Vietnam.” How could I—a woman, not a veteran, not even the right age to have been in Vietnam—presume to write about combat there? I really sweated it. During that period my husband would wake up in the morning, see me lying there exhausted after a failed night’s sleep, and say, “are you going ‘in-country’ again today?”

We’ve all heard the adage “write what you know.” The reason I was so stressed was because I was absolutely not writing what I knew—at least on the surface. But the story demanded it and so I waded in. I crawled inside the character of Adam—a gay man, a Marine in Vietnam who, thirty-five years later, is dying of MS—and from inside him, with the structure of the story for, well, structure, I discovered an amazing thing. There was something completely familiar about Adam. Emotionally, I recognized parts of myself in him: his outsiderness, his sensitivity, his difficult childhood, his desire to prove himself, his loyalty, his heartbreak at the cruelties of the world. So many familiar emotional parts. I explored all of that in the writing and then basically downloaded that emotional content to the story.

I’d been doing this all along with all the characters I’d ever written, I’d just never thought about it this way. But I also understood in a new and real way that this is why I write novels: for the chance to live lives so seemingly different from my own, for the chance to live many lives in this one life. It became a practice for me, much like a meditation practice, to step inside of my characters and learn what it might be like to be somebody who committed murder at eighteen years old, or somebody who was a black janitor and died in an anti-war bombing. Writing this way, as in a meditation practice, the opportunity to learn empathy and compassion is there.

In his 2000 introduction to Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out, Michael Cunningham wrote, “If it is the activist’s responsibility to depose the tyrant it is the novelist’s responsibility to understand and record what it’s like to be the tyrant.”

Yes, I agree, and I would add that it is the novelist’s responsibility and also her joy to understand and record what it’s like to be the victim, the innocent bystander, the accomplice, the girl who blew up a building in 1971, the janitor who died in the bomb blast, the revenge seeking ex-comrade, the husband, the child and yes, the brother who is a gay man dying of MS, remembering what it was like to be a soldier in Vietnam.

20 May 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.