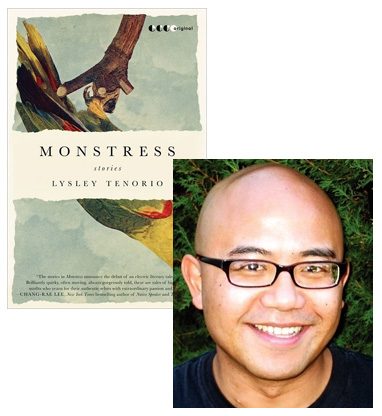

Lysley Tenorio On Dying & Character Development

The stories in Lysley Tenorio’s Monstress cover a wide range of Filipino and Filipino-American experiences, from a teen’s confused efforts to help his Imelda-fixated uncle exact revenge against the Beatles for a perceived offense during their 1960s visit to Manila to two elderly men who’ve spent their adult lives together in San Francisco’s International Hotel, from an actress in grade-Z monster movies who follows her husband on a desperate trip to Hollywood and discovers an unforeseen opportunity to a contemporary young man struggling to come to terms with the death of his transsexual younger sibling. There’s also a fantastic story, “Superassassin,” in which a teenage boy schemes to exact vicious revenge against his tormentors while caught up in his comic book-inspired fantasies. Tenorio comes by his portrayal of comics fandom honestly, as we’ll discover in this essay, and it’s also played an interesting role in shaping his literary vision.

I loved a girl once. For almost ten years. She was kind and selfless, a girl of unmatched courage, stronger than anyone I knew.

Then, when I was twelve years old, she died.

Her name was Kara. Kara Zor-el.

You might know her as Supergirl.

It was 1985. DC Comics had released Crisis On Infinite Earths, a 12-part series designed to streamline the overstuffed and overcomplicated DC Universe of multiple and parallel earths. In issue #7, Supergirl squares off against the Anti-Monitor, an all-powerful ruler of an Anti-Matter universe determined to destroy our own. It was a battle for the ages: just as the Anti-Monitor is about to kill her cousin, Superman, Supergirl swoops in, pummels the crap out of the Anti-Monitor, but on the verge of victory, she makes one fatal mistake: she looks away. With that, the Anti-Monitor unleashes his deadliest force-blast, killing her. But for the meantime, Supergirl has managed to disable his weapons, temporarily foiling his plans. “Thank heavens…” Supergirl says in her final breaths, “…the worlds have a chance to live…” Then, in Superman’s arms, she dies.

I finished reading it inside the comic book store, paid for it, then went with my sister to Pizza Hut. But I couldn’t eat. I felt numb. I felt dizzy. Across the table, my sister looked at me like I was an idiot, mourning a make-believe character, a girl of two dimensions. But I knew: This was grief. It had to be.

Lately, there has been a lot of dying in my classroom. In my freshmen fiction workshop, my students have been killing off their characters with cancer, brain tumors, car crashes, hit men, and comas from which they never awake. And they render these deaths with a gusto that’s admirable: they know the effect they want, and they go for broke, indulging every tear, breakdown, and bloodspurt. But for the most part, it doesn’t work. Reading these stories, we might find something recognizable or familiar (“Someone died at my high school too!”), but at most we understand these spectacular deaths, but we don’t feel them.

The problem isn’t necessarily the death itself; death is an intriguing and potent subject for fiction. The problem is the lack of life preceding it, the absence of that singular life force that every fictional character must possess in order to earn the right to die. We can only feel so much from the summarized life.

When I read these stories, I want to tell them about Supergirl. I was a living witness to the destruction of her home, Argo City (a sort of final city-remnant of Krypton, which exploded years before). I knew her as Linda Lee, the alias she assumed at the Midvale Orphanage, and that she had two pets: Comet the Superhorse and Streaky the Supercat. And when she wasn’t Supergirl, when she was simply Linda, she had the ambition and aimlessness of young adulthood—she was a high school counselor one day, an aspiring TV reporter the next, a soap opera actress soon after. I knew her powers and weaknesses, her losses and loves, her allies and nemeses, her victories and defeats. All that super-living, measured against a gloriously epic death scene. No wonder it worked. No wonder I mourned her.

I don’t assign my students Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 to demonstrate models of good dying. Instead, we read Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain” to see how the death of the loyal but reckless Jack Twist silently—by necessity—devastates his life-long lover, Ennis Del Mar. I assign Alice Elliot Dark’s “In the Gloaming,” which details the last days shared between Janet and her son, Laird, who is dying of AIDS, and how Janet comes to understand her life because of them (“Suddenly she realized: Laird had been the love of her life”). Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried” is a fine example of how a life, when simply represented by one’s personal possessions, can make a sudden and violent death even more wrenching. And death needn’t be defined as simply tragic: We read Donald Barthelme’s “The School” to examine the ways a writer renders the absurdity of dying, of mortality—all those school kids and their dying classroom pets. Whether we get the sweep of an entire life, or just a handful of its defining moments, these stories illustrate perfectly how to effectively and convincingly kill off a character. Their deaths shock us, rattle our heads, punch us in the gut. They make us grieve.

The students in my writing workshops are allowed to write whatever they want, whatever gets them excited about writing. But for my next freshman level workshop, I’m thinking of instituting a new policy: no killing off your characters. No cancer or brain tumors. No out-of-the-blue hit men, fatal teenaged drunk driving accidents, or coma-inducing blows to the head. No fatal force-blasts from all-powerful rulers of anti-matter universes.

At least, not until they’ve had a chance to live.

6 February 2012 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.