Carolyn Turgeon: What Lies Beneath Cinderella

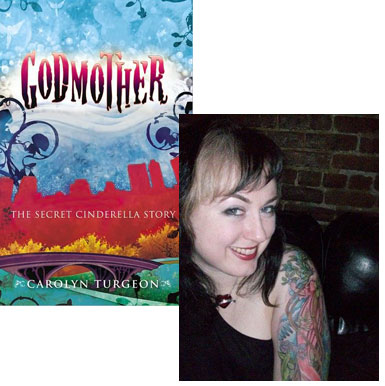

It’s been nearly two-and-a-half years since my friend Carolyn Turgeon wrote her first guest essay for Beatrice; the publication of her second novel, Godmother, is a perfect opportunity to hear from her again. (She’ll be reading from the novel at the Tribeca Barnes & Noble tonight at 7 p.m., if any of you reading this happen to be in New York City.) She offered to explain how she chose a familiar fairy tale as the basis for her story, and how she began diverging from the well-known story almost immediately…

When I started writing Godmother: The Secret Cinderella Story, I really just wanted to tell the Cinderella story straight-up. With lots of lush, shimmery language and images, lots of rich feeling, all kinds of twists and turns and secret little crevices of the story being revealed. I liked the idea of working with the Cinderella story, because: 1) it was already written, thus halving my work (I thought), and 2) it is just about the prettiest story in the world. Glass slippers and pumpkins and ball gowns and palaces!

And I’m not going to lie: the Cinderella that wormed its way into my deepest heart at a shockingly young age is the Disney one. No stepsisters cutting their heels off to fit into the shoes, no horrific comeuppances… and one puffy cheeked little fairy godmother flitting around to make all Cinderella’s dreams come true.

I also knew, right away, that any retelling of the Cinderella story I’d do would have to be sad. It’s a classic tale of longing: a young girl, abused, betrayed, lost, mistreated, her parents dead, stuck in the house of a woman who hates her, of her stepsisters who hate her, being forced to dress in rags and clean day and night, with nothing to do but imagine every single thing she’s lost or will never have. Her dead parents, her former happiness. The prince, the ball. Becoming someone new.

I have an enormous appreciation of longing. I’ve loved Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave since I was a teenager. I studied medieval Italian poetry in graduate school. I read about theologians and saints. I love quotes like this, from Nick Cave’s The Secret Life of the Love Song:

“We all experience within us what the Portuguese call Saudade, which translates as an inexplicable longing, an unnamed and enigmatic yearning of the soul and it is this feeling that lives in the realms of the imagination and inspiration and is the breeding ground for the sad song, for the Love Song. The Love Song is the light of God, deep down, blasting up through our wounds.”

So here is Cinderella, suffering, full of desire and Saudade. And the ball: it’s a real thing and also the object of every unnamed, inexplicable desire. Isn’t it? How is this poor, dirt-streaked girl going to get to the spectacular, otherworldly ball, anyway? How is she going to be transformed? It’s not the prince who saves Cinderella, after all. The prince just gets hot and bothered over a gorgeous girl in see-through shoes. It’s the fairy godmother who sees past the dirt, the pain and the heartbreak, to all the beauty hidden there.

But who is she, this fairy godmother who shows up to send Cinderella to the ball?

I knew pretty quickly in that I wanted to tell the godmother’s story. I also decided early on to make her an old woman living in present-day New York City, remembering what happened long ago. Because something had to have gone wrong. (Plus I figured I needed to balance out all that prettiness and pretty sadness with some grit and dirt and landlords and money woes, not to mention some of New York’s enchantments.)

I mean: how do you save a girl who has got to be past saving? How do you put this damaged, lost girl into a ball gown and slippers, send her to a prince, and have her live happily ever after? And how do you, a fairy, react to all that pain and longing? Wouldn’t it affect you somehow? Can you really be in the business of saving without becoming changed yourself?

And imagine: you’re a fairy. You live in a perfect, gorgeous world where you never experience desire or longing of any kind, ever. And then you come across a girl like Cinderella, covered with ash, swept up in Saudade. Wouldn’t you envy her, just a little? Couldn’t you get swept up in that same feeling, that this ball, this prince, this night… that all of it could fill you, finally, so perfectly you would be happy forever after? It doesn’t matter that you’re happy already. Couldn’t a fairy be as perverse as any of the rest of us who long, inexplicably, for other worlds?

This is where the Cinderella story took me, once I started writing. I figure the unhappily after can be beautiful, too.

26 March 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.